Presentation

A 76-year-old Caucasian gentleman presented to an outside optometrist with redness, blurred vision and pain in his left eye that had been present for nearly two months. He was initially diagnosed with a non-specific conjunctivitis and treated with topical antibiotic drops. The left eye redness and pain didn’t resolve, however, and he sought a second opinion several weeks later with a community ophthalmologist, who diagnosed him with scleritis and prescribed prednisolone acetate 1% four times per day. The topical steroid, however, didn’t provide the patient with any relief. He was referred to the Wills Eye Hospital Uveitis Clinic for further evaluation of his “treatment-resistant scleritis.”

|

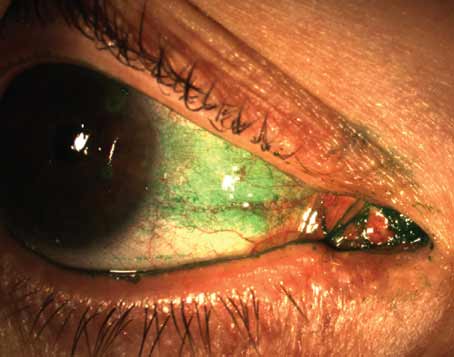

| Figure 1. External photograph revealing corkscrew injection of conjunctival vessels of the left eye. |

Medical History

The patient, a retired schoolteacher, had a past ocular history that was significant for primary open angle glaucoma, treated in both eyes with latanoprost drops once per day in the evening and timolol drops twice per day. His medical history was significant for hypertension, for which he was taking metoprolol succinate 25 mg per day, and hypercholesterolemia, for which he was taking atorvastatin 10 mg per day. He also took aspirin 81 mg per day as primary prevention. The medical history also included prostate cancer in remission.

Past surgical history included cataract extraction with placement of a posterior chamber intraocular lenses in both eyes and a repair of an abdominal hernia. Family history was noncontributory. Socially, the patient reported drinking one alcoholic drink per day, but denied tobacco and illicit substance use. Review of systems was positive for chronic floaters, occasional transient diplopia, “sinus-type” headache behind his left eye and recent trauma (he fell down the stairs without trauma to head or loss of consciousness).

Exam

The patient’s vision was 20/20 OD and 20/20-2 OS. Pupils were round, equally reactive to light, and didn’t reveal an afferent pupillary defect. Intraocular pressure was within normal limits, though slightly higher in the affected eye (16 mmHg OD, 20 mmHg OS). Visual fields were full to confrontation and Ishihara color plates were full.

Anterior segment exam of the left eye at the slit lamp revealed corkscrew injection of blood vessels without scleritis or ciliary flush (Figure 1). The cornea was clear without keratic precipitates, edema or infiltrate. The anterior chamber was deep and quiet and there was no blood in Schlemm’s canal on gonioscopy. The iris was flat without nodules or posterior synechiae. There were focal radial transillumination defects at 5 o’clock. There was a PCIOL with trace posterior capsule opacification. Slit lamp exam of the right eye was normal.

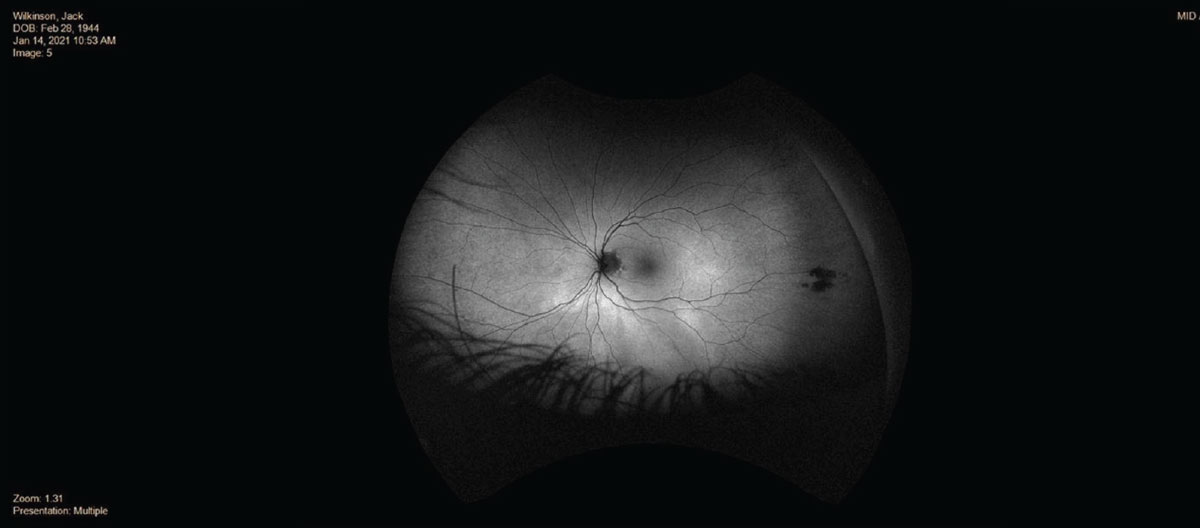

Dilated fundus exam of the left eye revealed two clumped intraretinal hemorrhages in the inferotemporal macula (Figure 2). The vitreous was clear, the optic nerve sharp and pink, the retinal vessels were of normal caliber and course, and the periphery was flat without lesions. Dilated exam of the right eye was normal. A stethoscope revealed no bruit over the orbit.

|

| Figure 2. Fundus autofluorescence of the left eye showing clumped intraretinal hemorrhages in the inferotemporal macula. |

What is your diagnosis? What further workup would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

At this point, the patient was brought to Wills Eye’s Neuro-ophthalmology Clinic. Further examination revealed a proptosis of 5-mm difference (Hertel Base 100: 16 OD, 21 OS). Oculomotor exam found flick of left hypertropia in primary, 2 prism diopters in left gaze, 3 PD in downgaze, flick in right gaze and 0 PD in upgaze.

Differential diagnosis included vascular lesions (such as carotid cavernous fistula, orbital arteriovenous malformation), thrombus, tumor (primary versus metastasis), thyroid eye disease and other orbital inflammatory processes. The location of the lesion had been narrowed at this point to the orbit or the cavernous sinus.

The patient underwent MRI and MRA the same day in the Wills Emergency Room. MRI revealed enlarged extraocular muscles with sparing of the tendinous insertions (consistent with thyroid-associated orbitopathy) but no features of cavernous carotid fistula, no acute infarct, no intracranial hemorrhage and no aneurysm in the Circle of Willis.

|

|

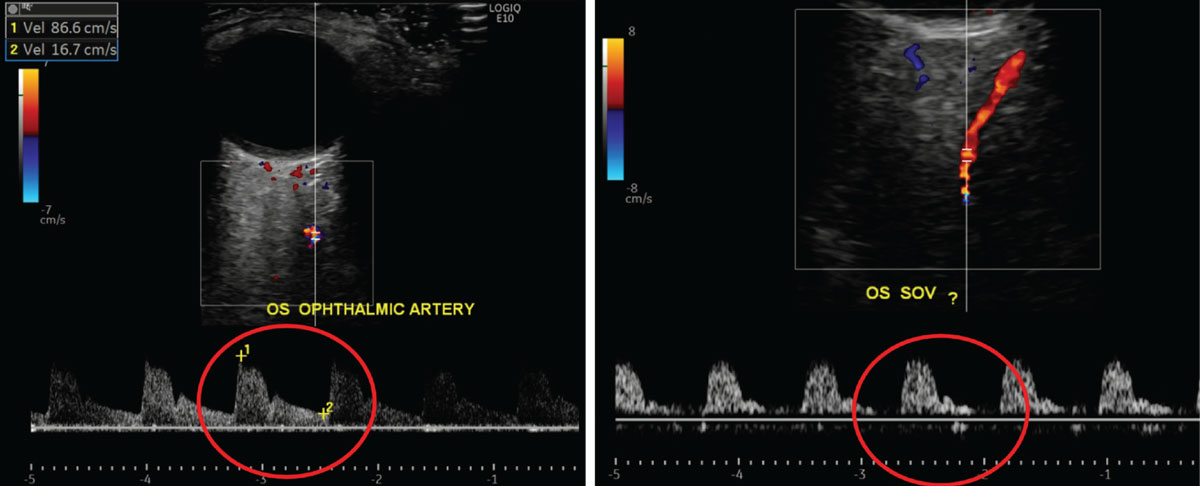

Figure 3a (left). Orbital doppler ultrasound showing the normal waveform of the left ophthalmic artery. Figure 3b (right). Orbital doppler ultrasound showing the abnormal arterialized waveform of the left superior ophthalmic vein. |

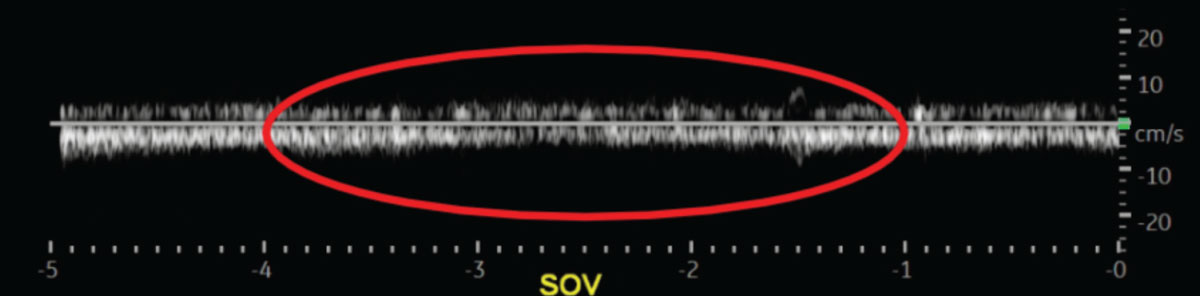

The patient also underwent carotid and orbital doppler ultrasound testing. The carotid ultrasound was within normal limits. The orbital ultrasound revealed an arterialized left superior ophthalmic vein, consistent with dural-cavernous arteriovenous malformation or carotid-cavernous fistula (Figure 3). The neurosurgical service was then consulted, promptly performed cerebral angiography and confirmed the diagnosis of a Barrow Classification Type-D carotid-cavernous fistula.

|

|

Figure 3c. Orbital doppler ultrasound showing a normal waveform of the right superior ophthalmic vein (the patient’s unaffected eye) for reference. |

Discussion

Carotid-cavernous fistulas are potentially life-threatening conditions that often present first to the ophthalmologist. The classic triad includes pulsatile exophthalmos, orbital bruit and chemosis,1 but the presentation can vary significantly. Symptoms can include diplopia, orbital/retro-orbital pain, headache, pulsatile tinnitus, vision loss and facial paresthesia. Signs also vary widely and include:

- eyelid edema (sometimes leading to ptosis);

- proptosis;

- ocular misalignment of any pattern;

- elevated IOP (sometimes with resultant glaucoma in the setting of elevated episcleral venous pressure, angle closure or neovascularization);

- injection;

- chemosis;

- conjunctival arterialization (the classic “corkscrew vessels”);

- disc edema;

- optic neuropathy;

- dilated retinal veins;

- retinal hemorrhages;

- central retinal vein occlusion; and

- choroidal detachment.1,2

Broadly, CCFs are categorized by their flow: high flow (direct connection between the internal carotid artery and cavernous sinus) versus low flow (connections between the meningeal branches of the internal or external carotid artery and the cavernous sinus).2

The diagnosis of CCF is greatly aided by orbital doppler, with a sensitivity of 97 percent (compared to 44 percent for CT and 58 percent for MRI).3 The typical imaging findings include an arterial wave form, an enlarged superior ophthalmic vein, or reversal of flow. Its utility is most noted in CCFs with anterior drainage (through the superior ophthalmic vein).

The treatment goal in CCFs is to occlude the fistula and maintain carotid artery blood flow. Conservative management includes compression of the ipsilateral carotid artery and jugular vein with the contralateral hand several times per day for four to six weeks.1 This conservative treatment is only appropriate for low-flow fistulas. Interventional management of CCFs includes endovascular, surgical or radiosurgical treatment. Endovascular is typically the treatment of choice and is 80- to 90-percent successful.4 If endovascular interventions fail, surgical treatment is attempted. Radiosurgical treatment is quite effective but has a latency period of several months.4

Symptom resolution ranges from hours and days to weeks and months depending on the severity and chronicity of the fistula.1 There is also a transient worsening that approximately 40 percent of patients experience prior to symptom resolution.5

The neurosurgical team elected conservative management for our patient. He’s improving clinically with less pain, proptosis and no further diplopia. Ophthalmologists are typically the first physicians to whom CCF patients present, and it’s important to have a high degree of suspicion in a patient with a unilateral condition that’s treatment-resistant and has a possible etiology of elevated venous pressure posteriorly.

1. Elias JA, Goldstein H, Connolly ES Jr, Meyers PM. Carotid-cavernous fistulas. Neurosurg Focus 2012;32:5:E9.

2. Tan AC, Farooqui S, Li X, Tan YL, Cullen J, Lim W, Leng SL, Looi A, Tow S. Ocular manifestations and the clinical course of carotid cavernous sinus fistulas in Asian patients. Orbit 2014;33:1:45-51.

3. Srinivasan A, Biro NG, Murchison AP, Sergott RC, Moster ML, Jabbour PM, Bilyk JR. Efficacy of orbital color doppler imaging in the diagnosis of carotid cavernous fistulas. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2017;33:5:340-344.

4. Tjoumakaris SI, Jabbour PM, Rosenwasser RH. Neuroendovascular management of carotid cavernous fistulae. Neurosurg Clin N Am 2009;20:4:447-52.

5. Sergott RC, Grossman RI, Savino PJ, Bosley TM. The syndrome of paradoxical worsening of dural-cavenrous sinus arteriovenous malformations. Ophthalmology 1987;94:3:205-212.