Earlier this year, pegcetacoplan made history as the first FDA-approved therapy for geographic atrophy. Commercially marketed as Syfovre (Apellis), pegcetacoplan showed a clinically meaningful reduction in geographic atrophy lesion growth, giving hope to a group of patients who previously had no recourse to slow their significant vision loss.

Syfovre’s approval is just the first of what may be the coming wave of geographic atrophy treatments. In February, the FDA accepted Iveric Bio’s new drug application for avacincaptad pegol (Zimura) for the treatment of GA. It’s possible avacincaptad pegol could be approved by the time this article is published. There’s much more in the pipeline, too, and retina specialists are excited about the possibilities while remaining cautious. We spoke with several physicians to find out how pegcetacoplan works, its safety profile and what it all could mean for patients.

The Challenges of Geographic Atrophy

The last stage of dry age-related macular degeneration, geographic atrophy results in progressive and eventually permanent vision loss. Contributing factors to GA include genetics, environment and age, and historically, ophthalmologists had little relief to offer patients other than recommendations to maintain a healthy lifestyle, avoid smoking and take dietary supplements such as vitamin C, vitamin E, beta-carotene and zinc.1

This has amounted to frustration on behalf of both the patient and physician.

“Historically, geographic atrophy patients are one of the few subsets of patients that we can’t help, and this has been a huge source of frustration for us,” says Ashkan Abbey, MD, a medical and surgical retina specialist and the director of clinical research for Texas Retina Associates in Dallas. “We’ve been essentially watching them deteriorate in front of our eyes and all we can offer are low-vision aids, but we haven’t really had much to help them or to slow down the process.”

The disease can also impact a patient’s mental health, says Jaclyn Kovach, MD, FASRS, a professor of clinical ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miller School of Medicine, University of Miami. “Ultimately, most patients with GA need a caregiver to help with their activities of daily living. There are so many secondary effects from GA,” she says. “Because of poor vision, patients often withdraw from social interaction and lose their independence as they are unable to drive, and consequently suffer from depression.”

“As physicians, we don’t like saying there’s nothing we can do for them,” says Ananda Kalevar, MD, a vitreoretinal specialist and an associate professor and program director at the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec. “They often know friends or family who are receiving injections for wet AMD and end up disappointed when we tell them there’s nothing like that for dry AMD.”

That’s all changing with the approval of pegcetacoplan. “Our patients have been waiting for years for a treatment for GA,” says Dr. Kovach. “These groundbreaking treatments will give them an opportunity to slow the progression of their disease so they can potentially retain the vision that they have longer. Treatment empowers them to play a role in modulating the future of their disease.”

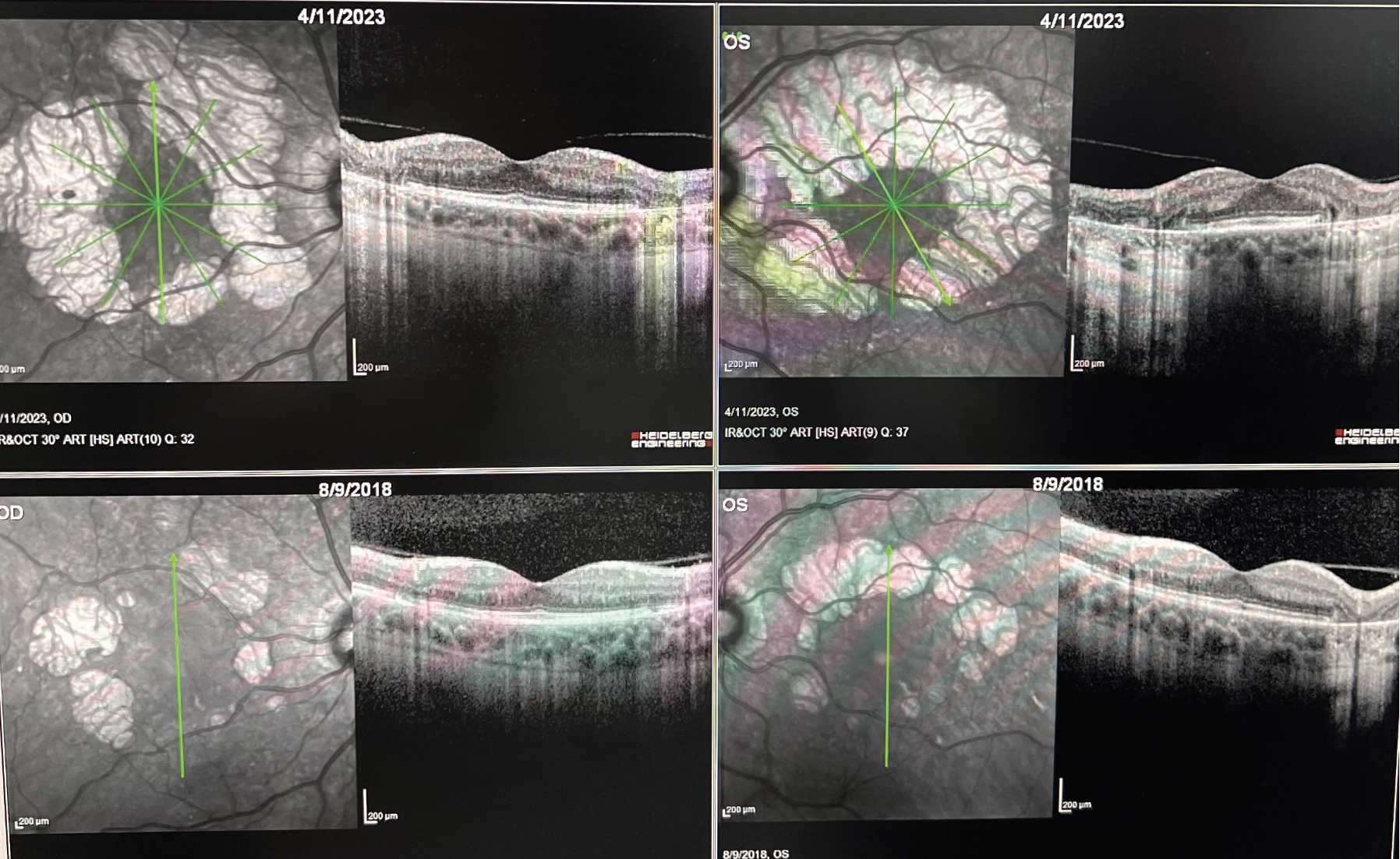

|

| OCT images demonstrating progression of extrafoveal geographic atrophy over the course of 4 1/2 years in both eyes. The bottom row demonstrates the baseline OCTs for the right and left eyes. Early intervention with a complement inhibitor could significantly reduce the rate of atrophy in this case. (Courtesy Ashkan Abbey, MD). |

How These Therapies Work

Both pegcetacoplan and ACP target the complement cascade, which is composed of part of the immune system, and comprises three pathways that include plasma and membrane-associated serum proteins, some of which have been linked to the development and progression of dry AMD.2 The dysregulation of the complement system has been the focus of therapy development, but it hasn’t always been successful.

Previously, in 2018, lampalizumab (Genentech) was a therapy targeting complement factor D, and it advanced to Phase III Chroma and Spectri randomized clinical trials. After 48 weeks of treatment, however, lampalizumab failed to reduce GA enlargement vs. sham.3

“Research has focused a lot on the complement pathway when it comes to trying to slow down geographic atrophy,” says Dr. Abbey. “I think a lot of us were getting frustrated because we kept striking out. We had the issues with lampalizumab where it didn’t end up meeting its endpoints for Phase III trials, and there have been multiple other examples of different agents that tried to target the complement pathway and failed in the last 10 years. The numerous failures led some people in the community to start saying, ‘Well, maybe we need to stop thinking about complement because it just doesn’t seem like it’s working out.’ ”

Dr. Abbey says pegcetacoplan inhibits C3 and C3b in the complement pathway. “By inhibiting C3 and C3b, one of the important downstream effects involves a reduction in the rate of formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC), which is what leads to apoptosis (cell death) of retinal cells for many of our patients when they have geographic atrophy,” he says.

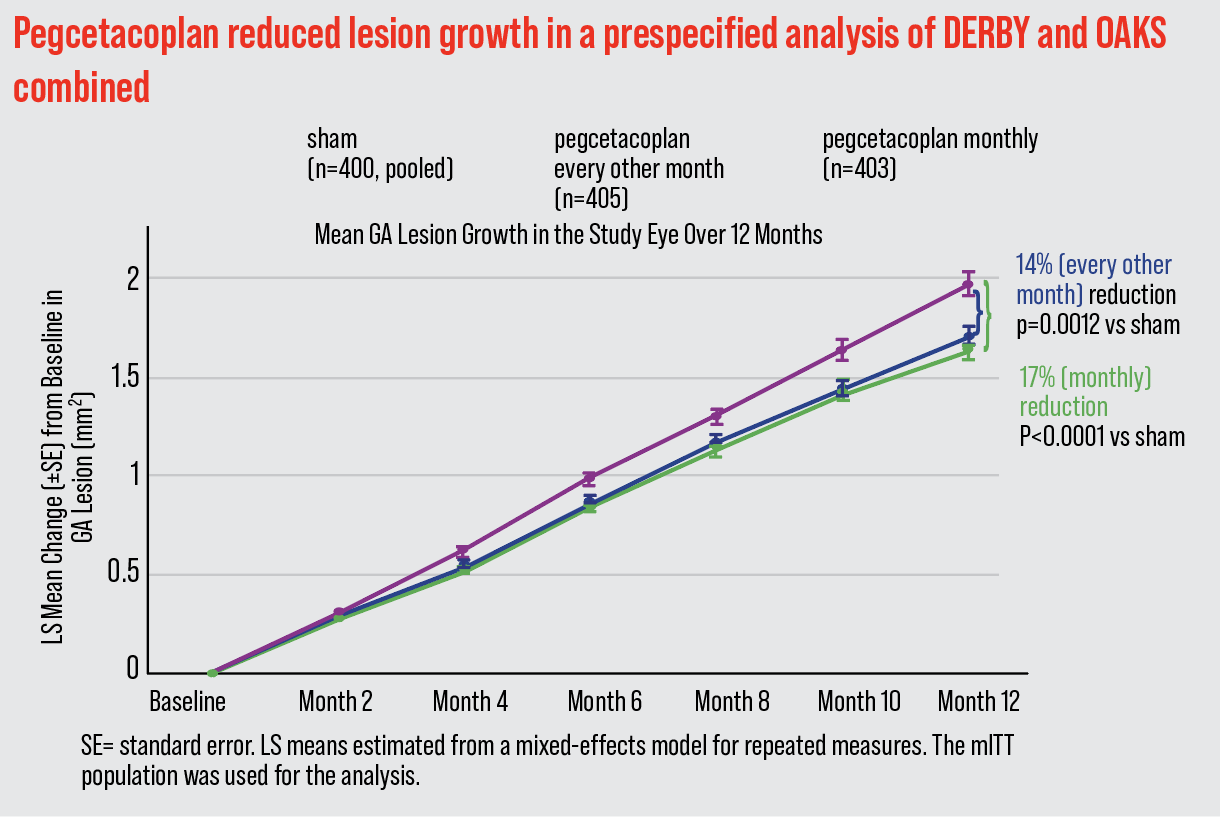

In the results of the combined studies, dubbed OAKS and DERBY, patients received intravitreal pegcetacoplan monthly or every other month. After 12 months, GA lesion growth rate was reduced by 17 percent (p<0.0001) and 14 percent (p=0.0012) monthly or EOM, respectively, vs. sham.4 After 24 months, there was an increased reduction of 26 percent (monthly) (p<0.0001) vs. sham, and 23 percent (EOM) (p=0.0002) vs. sham in patients with extrafoveal lesions.4 Dr. Abbey, who participated in the clinical trials, notes that these figures represent pooled data.

“In one of its trials (OAKS), pegcetacoplan showed significance in terms of its effect on the rate of reduction of the lesion size in patients with GA compared to sham, whereas the other trial (DERBY) didn’t show significance when compared to the sham,” Dr. Abbey says. “However, when the two different Phase III trials’ endpoints were pooled together, the data did show significance. That was enough for the FDA to approve it in the end, but that has led to one of the criticisms that it was only one pivotal trial that showed significance in terms of the reduction in the rate of advancement of GA over time.”

|

| The combined results of the OAKS and DERBY clinical trials showed a reduction of 17 percent (p<0.0001) in patients receiving monthly pegcetacoplan therapy vs. sham, and 14 percent (p=0.0012) every other month vs. sham. |

Dr. Kalevar says this is an exciting time in retina. “This gives us something to offer patients and it’s only the first iteration, but it will get better and better and more efficient,” he says.

However, with any treatment, the number one goal is safety, he continues. “I will say I’m a little concerned about the side effect profile,” says Dr. Kalevar. “In the retina community, we recently had an experience with a therapy that burned us, so we have a bad taste in our mouth. We got really excited about the numbers we saw in terms of improvement for that drug, but we sort of glossed over the signals of safety issues. And then, in postmarketing data, we figured it out.”

Dr. Kalevar is referring to brolucizumab (Beovu, Novartis), which was approved for wet AMD in 2019. Within months of that approval, retina specialists were alerted to reports of retinal vasculitis attributed to the drug. It’s a lesson learned in the back of every retina specialist’s mind.

“One thing we’re all concerned about in the retina community regarding Syfovre—after what we went through with brolucizumab—is if there’s inflammation that’s significant enough that can cause vasculitis or occlusive vasculitis,” says Dr. Abbey. “In the clinical trials, we didn’t have any evidence of vasculitis or occlusive vasculitis, which was reassuring. But we remain wary because in the trials that get FDA approval, we often don’t have sufficient numbers to detect a significant signal for a more rare event that could be visually devastating like that. It’s going to be important to see what happens with the real world data as time passes and more injections are performed.”

Dr. Abbey continues, saying the American Society of Retina Specialists released a report of a small number of cases of intraocular inflammation and vasculitis associated with Syfovre since its approval. “We are awaiting additional information regarding the specific details of these cases,” he says.

Issued in mid-July, the letter from ASRS informed members of its community that its Research and Safety in Therapeutics (ReST) Committee received reports from physicians of intraocular inflammation, including six cases of occlusive retinal vasculitis, all of which were observed between seven and 13 days after Syfovre was administered, according to the letter. The ASRS urged vigilance and close follow up, stating the significance of this real-world data. “Particularly in the setting of a newly approved drug or device, such reports are critical in defining our real-world experience through analysis of the aggregate of collected reports,” the ASRS said in the letter. It further reminded members to follow sterile injection protocols as outlined in the Syfovre prescribing information.

Another of the concerns regarding pegcetacoplan is the increased rate of choroidal neovascularization (conversion to wet AMD). According to the combined Phase III results, CNV was reported in 11.9 percent of eyes treated monthly, and 6.7 percent in eyes treated EOM, compared to sham (3.1 percent).5 “If we’re treating someone for geographic atrophy and then they end up getting CNV, if you’re in a high-volume practice, that’s a lot of patients daily that I’m potentially converting to CNV by using pegcetacoplan,” says Dr. Kalevar.

Dr. Kovach says pegcetacoplan therapy could carry a small risk of anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, which was reported in 1.7 percent of patients treated monthly, 0.2 percent EOM and zero percent in sham.6 “Soon, we’ll have long-term clinical trial data and real-world data to better elucidate the prevalence of these risks,” she says.

Uptake Within the Field

As Syfovre makes its way into clinics across the country, it’s unclear how swift the adoption will be.

“I think there’s a spectrum of perspectives,” says Dr. Kovach. “Some retina specialists are waiting for long-term clinical trial data and real-world data, especially when it comes to elucidating the risk factors. Other retina specialists are excited to start treating patients.”

Dr. Abbey agrees there’s a subset of physicians who are simply opposed to using this therapy. “I’ve spoken with them. Their argument is that they don’t believe that the juice is worth the squeeze, so to speak, in these cases,” he says. “We have the data showing us roughly a 20 to 30 percent reduction at one year, in terms of the growth of GA lesions by using this injection once a month or once every other month, and to a lot of folks, that just isn’t good enough to be putting people through the substantial burden of treatment required to get to that point, along with other potential risks with administering injections that often.”

Dr. Kalevar places himself in that camp. “I think uptake is going to be very slow,” he says, adding that he’s alarmed by the recent safety reports released by ASRS. “Inflammation is one thing but vasculitis is another beast. At this point I wouldn’t use these drugs in my practice until more numbers come out showing better safety. We have to weigh causing potential harm vs. the natural progression of the GA, and I think people would rather the natural progression of the GA go through. If you have a patient who’s counting fingers because of geographic atrophy and they don’t want to lose it and they’re motivated because it’s a 20-percent reduction—that’s a big number, but we’re just talking about growth. It’s still growing. If something is close to the fovea and still growing, combined with the CNV rate, it’s a little bit hard to justify injecting these patients nonstop.”

That’s the real challenge for Syfovre to overcome, notes Dr. Abbey. “There will be those retina specialists who dig in and say, ‘Well, I’m not actually really helping their vision by doing this either, I’m just trying to slow things down a little bit, and the amount that I’m slowing things down is really not that impressive to me either,’ ” he says.

“On the other hand, we finally have a treatment for GA, which is great, and it does provide some hope for those patients who are desperate,” continues Dr. Abbey. “There are going to be some patients out there—I’ve treated them myself already—who believe that this is worth the commitment of time and the potential risk. They’re willing to deal with that potential treatment burden because they want to keep their vision for as long as possible. The disease has already affected their lives in significant ways. However, I do believe that there will continue to be a bloc of retinal specialists who probably will never be convinced to treat, at least with this iteration of complement inhibition treatment for the disease. Having said that, I know plenty of retina specialists who have already started using it, including myself, and we’ve been happy with the results so far—as happy as you could be for having Syfovre available for such a short period of time.”

Dr. Kovach recommends a thorough patient analysis and discussion before proceeding with pegcetacoplan injections. “Patients who I would favor treating first would be those who have lost vision in one eye because of AMD and have geographic atrophy encroaching on the fovea in the better eye,” she says. “I’d want to treat the better eye to try to slow GA progression as much as possible. The treatment decision requires an analysis of past GA progression on multimodal imaging, including fundus autofluorescence and OCT, and assessing progression biomarkers such as GA focality, location, banding pattern on FAF and reticular pseudodrusen, hyperreflective foci and drusen volume on OCT. Environmental factors, such as smoking, should also be considered. Finally, a detailed discussion with the patient reviewing how their disease is affecting their vision now, past GA progression, their untreated prognosis, risks, benefits and if they’re willing and able to come in every four to eight weeks to receive injections, is necessary.”

Therapies on the Horizon

Much more is in the pipeline for GA, and avacincaptad pegol (Zimura, Iveric Bio) is expected to garner FDA approval later this summer.

ACP is also a complement inhibitor, but targets C5. “ACP inhibits C5 in the complement cascade, which is more distal in the cascade and more directly related to MAC formation,” Dr. Kovach says. “The MAC complex is what directly leads to RPE cell death. ACP works to decrease MAC formation while preserving the functions of C3.”

Dr. Abbey says this is part of the appeal of ACP in the retina space. “When you’re inhibiting C3, you’re inhibiting everything downstream of C3 as well, but some of the parts of the complement pathway after C3 can potentially be a benefit, so you may not necessarily want to be inhibiting everything that’s downstream of C3,” he says. “For example, we do know that C3, when it’s normally activated, is cleaved into C3a and C3b, and C3a specifically can have some anti-inflammatory effects as well. So we may actually want to have more C3a around in a case where inflammation is causing us to have retinal degeneration, like in GA. It’s one of those instances where you go ahead and take complete C3 inhibition because you see that it does reduce the overall inflammation that leads to cell death, but maybe there’s also a potential where the C3a portion that’s cleaved could actually be helpful in the process of geographic atrophy and reducing the overall inflammation as well.

“If you inhibit at C5,” continues Dr. Abbey, “you don’t have to worry about that anymore because you’ll still have the C3a upstream being produced, and the inhibition of C5 will still lead to a reduction in the overall cell death process and overall inflammation without as much upstream effect on the complement pathway. It’s obviously more complicated than that, but that’s part of the reasoning why some people would argue that C5 inhibition may be more ideal for this disease.”

According to results from the GATHER1 and GATHER2 clinical trials, ACP showed a 27.4-percent (p=0.0072) reduction in the mean rate of GA growth in the 2 mg cohort and 27.8-percent (p=0.0051) in the 4 mg cohort, compared to sham.6 Among the most common adverse events reported at 12 months in the ACP 2 mg cohort were conjunctival hemorrhage (13 percent), increased IOP (9 percent) and CNV (7 percent).7

“Another reason why some would argue that ACP could be better than pegcetacoplan is that ACP had two pivotal Phase III trials that both showed significance, as opposed to just one with pegcetacoplan,” Dr. Abbey says. “Some people may feel that since ACP didn’t have to pool its data to achieve significance, it could mean C5 inhibition is a better data-driven option. However, I’ll point out that in ACP’s trial, it was administered monthly, so you have to consider that amount of burden on the patient. And just like pegcetacoplan, we did see that signal again with an increased rate of the neovascularization and conversion to wet AMD in the patients who were receiving ACP.”

As the field watches other trials progress, Dr. Kovach notes that oral therapy would be particularly appealing. She’s currently a principal investigator for danicopan (Alexion Pharmaceuticals), an oral factor D inhibitor that’s currently in a Phase II trial. Cognition Therapeutics also has an oral therapy in development, consisting of a “small molecule sigma-2 (σ-2) receptor modulator designed to penetrate the blood-retinal barrier and bind selectively and saturably to the σ-2 receptor complex” in Phase II of the MAGNIFY study, according to the company. Cognition says this therapy may protect RPE cells from key drivers of underlying disease.

“It would be great to have an oral medication to treat GA in both eyes and obviate the need for intravitreal injections,” adds Dr. Kovach.

Gene therapy may also prove beneficial, she continues. “Janssen has developed a gene therapy drug, JNJ-81201887, that expresses CD59 and that inhibits MAC formation. It’s administered via a single intravitreal injection, and it was well-tolerated in a 24-month Phase I clinical trial. We’ll have to see how it performs in the subsequent studies. There are many other investigational treatments moving through the clinical trial pipeline, so hopefully in the next couple of years we’ll have more treatment options in our armamentarium,” Dr. Kovach says.

Pearls for the General Ophthalmologist

Retina specialists feel there are some important elements for the general ophthalmologist to know and consider regarding these new therapies and the patients who may benefit.

“There should be a discussion of who’s an ideal patient to start on Syfovre (and eventually on Zimura as well, if it gets approved),” says Dr. Abbey. “That’s important because the comprehensive ophthalmologists are going to be the gatekeepers for a lot of these patients. Most of the time, they’re following these patients and not typically referring them to retina specialists because there was no available treatment for them in the past.”

It’s hard to define who the ideal patient is, but identifying certain characteristics of GA is essential. “Snellen vision often can’t capture how devastating geographic atrophy is for patients,” notes Dr. Kovach. “A patient can have significant functional vision limitations and still retain good central Snellen vision.” Retina specialists rely on fundus photography and OCT to detect and diagnose GA.

“GA can be a devastating disease,” she continues. “The ability to diagnose GA early and refer patients to retina specialists for evaluation and possible treatment can positively alter their disease course. Early treatment with the goal of slowing GA progression can give patients the opportunity to benefit from even more effective future next-generation therapies."

Dr. Abbey is involved with the trials for Syfovre and Zimura and is participating in other GA trials. He is also a speaker and consultant for Apellis and Iveric Bio. Dr. Kalevar reports no disclosures. Dr. Kovach is a principal investigator for Alexion and Apellis and a consultant for Iveric Bio, Apellis, Regeneron and Genentech.

1. AREDS Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial of high-dose supplementation with Vitamin C and E, beta carotene, and zinc for AMD and vision loss: AREDS report no. 8. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:10:1417-36.

2. Desai D, Dugel PU. Complement cascade inhibition in geographic atrophy: A review. Eye (Lond) 2022;36:2:294-302.

3. Holz FG, Sadda SR, Busbee B, Chew EY, Mitchell P, Tufail A, Brittain C, Ferrara D, Gray S, Honigberg L, Martin J, Tong B, Ehrlich JS, Bressler NM; Chroma and Spectri Study Investigators. Efficacy and safety of lampalizumab for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: Chroma and Spectri phase 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;1:136:6:666-677.

4. Apellis announces 24-month results showing increased effects over time with pegcetacoplan in Phase 3 DERBY and OAKS studies in geographic atrophy (GA) [press release]. Waltham, MA; Apellis Pharmaceuticals; August 24, 2022. Available at: https://investors.apellis.com/news-releases/news-release-details/apellis-announces-24-month-results-showing-increased-effects. Accessed July 10, 2023.

5. SYFOVRE Highlights of Prescribing Information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/217171s000lbl.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2023.

6. Jaffe GJ, Westby K, Csaky KG, Monés J, Pearlman JA, Patel SS, Joondeph BC, Randolph J, Masonson H, Rezaei KA. C5 inhibitor avacincaptad pegol for geographic atrophy due to age-related macular degeneration: A randomized pivotal phase 2/3 trial. Ophthalmology 2021;128:4:576-586.

7. Iveric Bio announces vision loss reduction data in geographic atrophy from avacincaptad pegol GATHER trials. March, 1, 2023. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20230228006487/en/Iveric-Bio-Announces-Vision-Loss-Reduction-Data-in-Geographic-Atrophy-from-Avacincaptad-Pegol-GATHER-Trials. Accessed July 17, 2023.