Presentation

A 34-year-old female presents to an outside emergency room with left eye vision going “in and out” for 20 to 30 seconds.

History

|

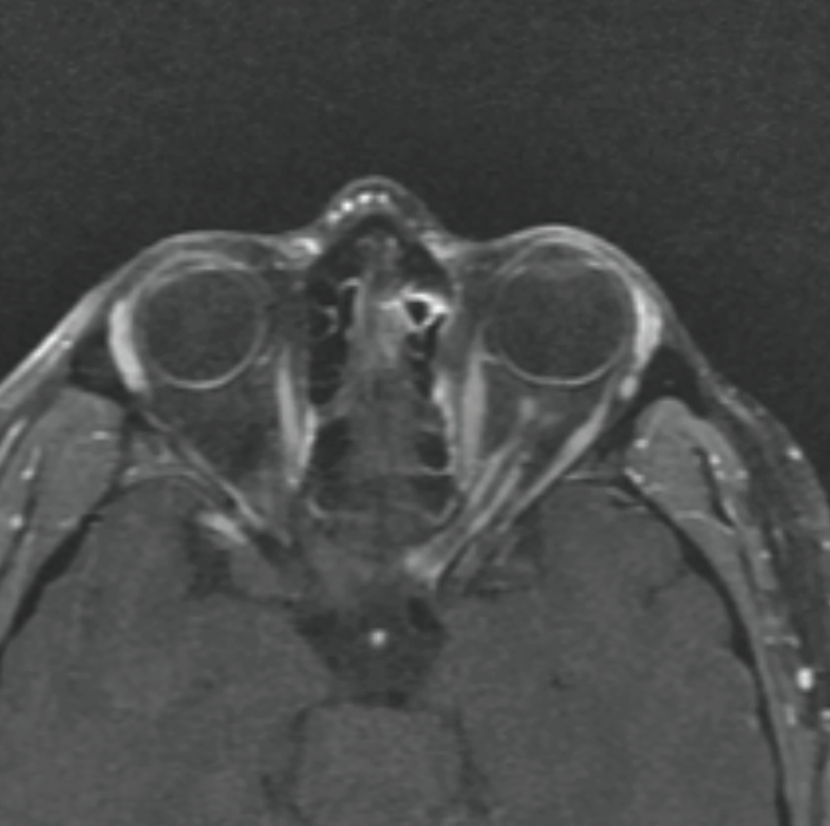

| Figure 1. T1-weighted post-gadolinium axial MRI showing left optic nerve sheath enhancement with a “tram track” appearance. |

At presentation, she didn’t report any past ocular history. Past medical history included asthma, obstructive sleep apnea, anxiety, depression, obesity and recent upper respiratory infections; past surgical history was non-contributory. Medications included an albuterol inhaler every six hours as needed, trazadone nightly, venlafaxine once daily, and a medroxyprogesterone injection (depot) once every three months.

Family history included Huntington’s disease in her maternal grandfather, aunt, and uncle; the patient herself had declined testing for the condition. She was a former 10-pack-year smoker with daily nicotine vape use at the time of presentation; she was also a former methamphetamine, MDMA and marijuana user, in remission for about nine months. She worked as a waitress and had three children. Allergies included ciprofloxacin (hives) and vancomycin (hives). Review of systems was negative for pain, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, weakness or numbness.

Initial Examination Work-Up

|

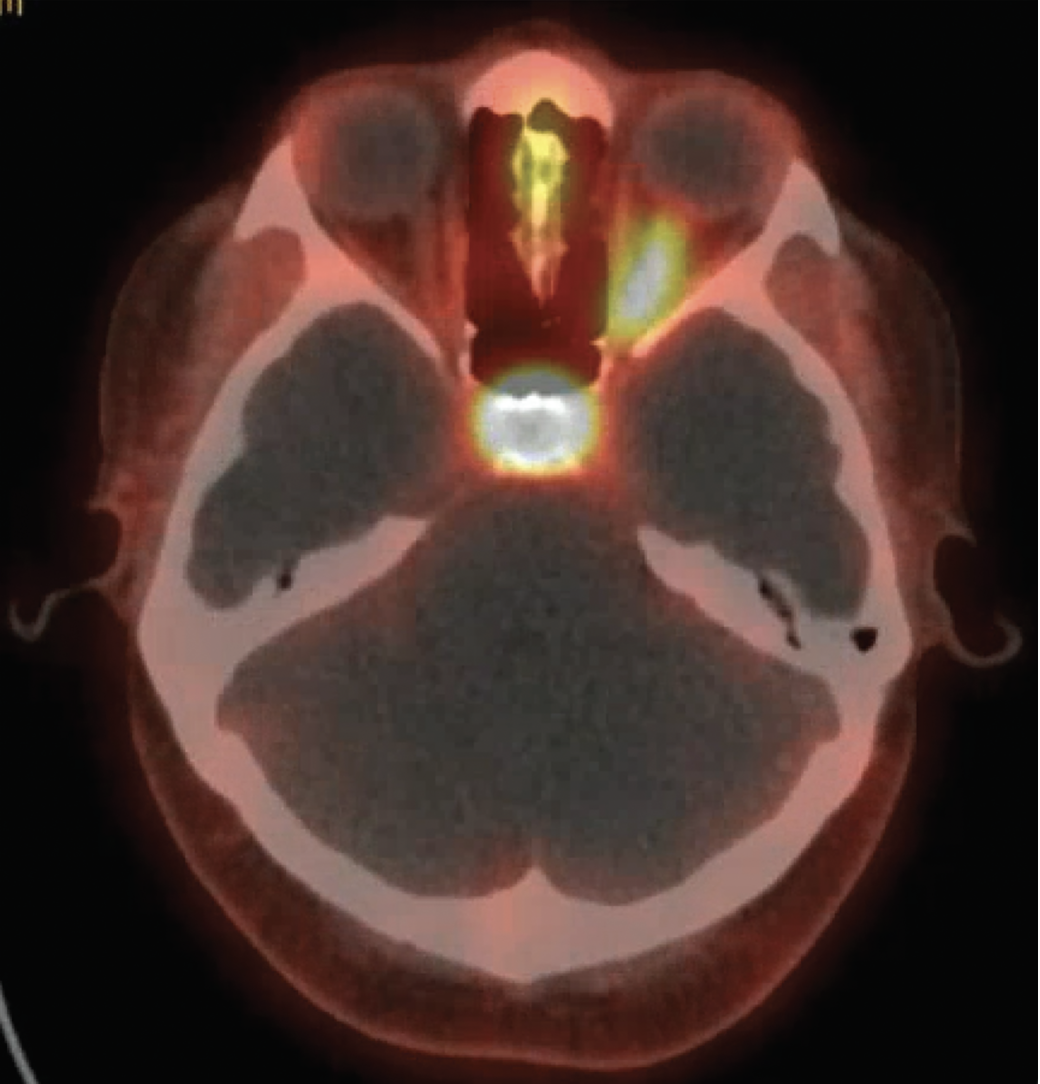

| Figure 2. CT scan of the orbits showing some enlargement of the left optic nerve with no evidence of optic nerve sheath calcification. |

On initial presentation to the outside ER, visual acuity without correction was 20/20 in both eyes. Intraocular pressure was 13 in the right eye and 14 in the left eye. Pupils were equal, round and reactive with a 2+ relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Motility and confrontation visual fields were normal in each eye. Color perception was normal in the right eye with 50 percent red desaturation in the left eye. External examination was unremarkable; anterior exam was normal. Posterior exam showed circumferential disc elevation with obscuration of major vessels and surrounding Paton’s lines in the left eye; in the right eye, the disc was flat and sharp with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.1.

In the ER, she underwent MRI of the brain and MRA of the head; both were unremarkable. Subsequent MRI orbits with gadolinium contrast showed “enhancement of the intraorbital and intracanalicular segments of the left optic nerve.” MRI of the C-spine and T-spine with gadolinium contrast did not show other lesions. Chest X-ray, ACE, NMO, MOG, ANA, ESR, CRP, Lyme, IgG4/IgG, Bartonella and FTA-Abs were normal. She was diagnosed with left optic neuritis and admitted for five days of intravenous methylprednisolone with some improvement in her visual symptoms; she was later discharged on an oral prednisone taper.

One month after initial presentation, an exam with an outside ophthalmologist re-demonstrated disc edema in the left eye. Repeat MRI orbits with contrast several weeks later showed “persistent thickening of the left optic nerve sheath with enhancement.” She continued on her oral steroids during this time.

Ten weeks after initial presentation, she re-presented to the outside emergency room with two weeks of intermittent blurred, “washed-out” vision in the left eye and numbness/tingling in the right upper extremity. MRI brain was again unremarkable. A lumbar puncture showed a normal opening pressure (20 mmHg) in the left lateral decubitus position, elevated oligoclonal bands (7 in the cerebrospinal fluid without correlating bands in the serum), normal protein (62), normal glucose (103), and an elevated white blood cell count (23, with 13-percent neutrophils) with zero red blood cells. MOG CSF antibody was negative. Given her new visual complaints, she was again admitted for three days of intravenous methylprednisolone and discharged on an oral prednisone taper; she reportedly had mild improvement in her vision at this time. Two weeks after discharge, she was seen by an outside neurologist and started on Rituximab for presumed “multiple sclerosis with recurrent optic neuritis.”

Eight months after the initial presentation, she awoke with complete loss of peripheral vision in the left eye with a preserved “slit” of blurred central vision. MRI brain and orbits with and without contrast showed “persistent thickening and enhancement of the left ON sheath; possible left thalamic T2 hyperintensity.” CT chest/abdomen/pelvis was negative for inflammatory process or malignancy. She was again admitted for four days of intravenous methylprednisolone and discharged on an oral prednisone taper. At this time, due to her worsening vision and overall atypical course, she was sent to the Wills ER for further evaluation and work-up.

In the Wills ER, visual acuity without correction was 20/25 in the right eye and 20/300 in the left eye. Intraocular pressure was 16 mmHg OD and 18 mmHg OS. Pupils were equal, round and reactive with a 3+ relative afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Motility was full in each eye; confrontation visual fields were normal in the right eye with diffusely constricted fields in the left eye. Color plates were full in the right eye, and she was only able to identify the control plate in the left eye. External examination was unremarkable; anterior exam was normal. Posterior exam showed circumferential disc elevation with obscuration of major vessels and surrounding Paton’s lines in the left eye; in the right eye the disc was flat and sharp with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.1. Rare anterior vitreous cells and focal RPE changes inferotemporal to the disc were seen in the left eye. MRI brain and orbits with contrast showed “tram track enhancement of the left optic nerve sheath extending from intraorbital through the canalicular segment”; given persistence of this abnormality, differential considerations included optic nerve sheath meningioma (Figure 1). A CT scan of the orbits was performed to look for calcification along the left optic nerve sheath to suggest optic nerve sheath meningioma, but this wasn’t identified (Figure 2). The patient was discharged with urgent neuro-ophthalmology follow-up.

What’s your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

|

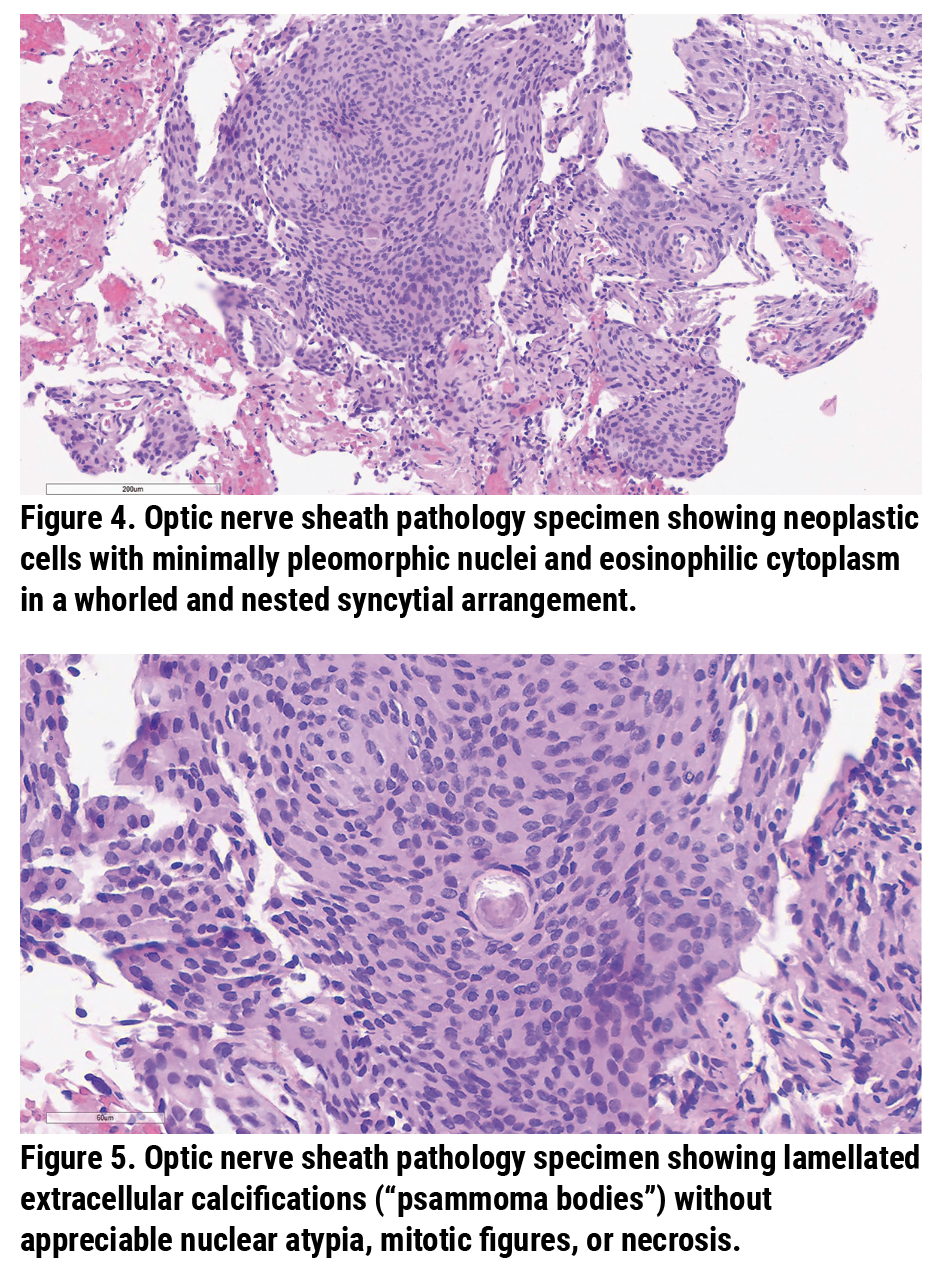

| Figure 3. Ga-68 PET scan showing intense radioactive uptake along the left optic nerve. |

Diagnosis and Treatment

Although the patient was suspected to have optic nerve sheath meningioma based on neuroimaging findings, her rapid progression over eight months and the presence of oligoclonal bands in the CSF would be atypical for this diagnosis. Therefore, a PET DOTATATE Ga-68 scan was ordered in attempt to clarify her diagnosis. These positron emission tomography scans use radiolabeled somatostatin receptors (SSTR) ligands (which are overexpressed in meningiomas) to better visualize meningiomas.1 Her scan showed “intense uptake along the left optic nerve [which] would support the pattern of enhancement of the left optic nerve on the recent MRI imaging to most likely be a meningioma… although sarcoid remains on the differential as it also expresses SSTR 2 receptors” (Figure 3). Because inflammatory optic neuropathy secondary to sarcoidosis typically responds to steroid treatment (and this patient had poor visual recovery despite multiple rounds of steroids), her diagnosis was presumed to be optic nerve sheath meningioma; radiation therapy was thus recommended.

|

However, during her follow-up visit, the patient stated she “would rather lose vision in [her] left eye completely from an [optic nerve sheath] biopsy” than to not have a definitive answer. She was referred to Oculoplastics where she was counseled extensively on the risks of severe, permanent vision loss if she were to proceed with an optic nerve sheath biopsy; after several visits, the patient persisted in seeking a pathologic diagnosis and ultimately underwent an optic nerve sheath biopsy via transorbital approach.

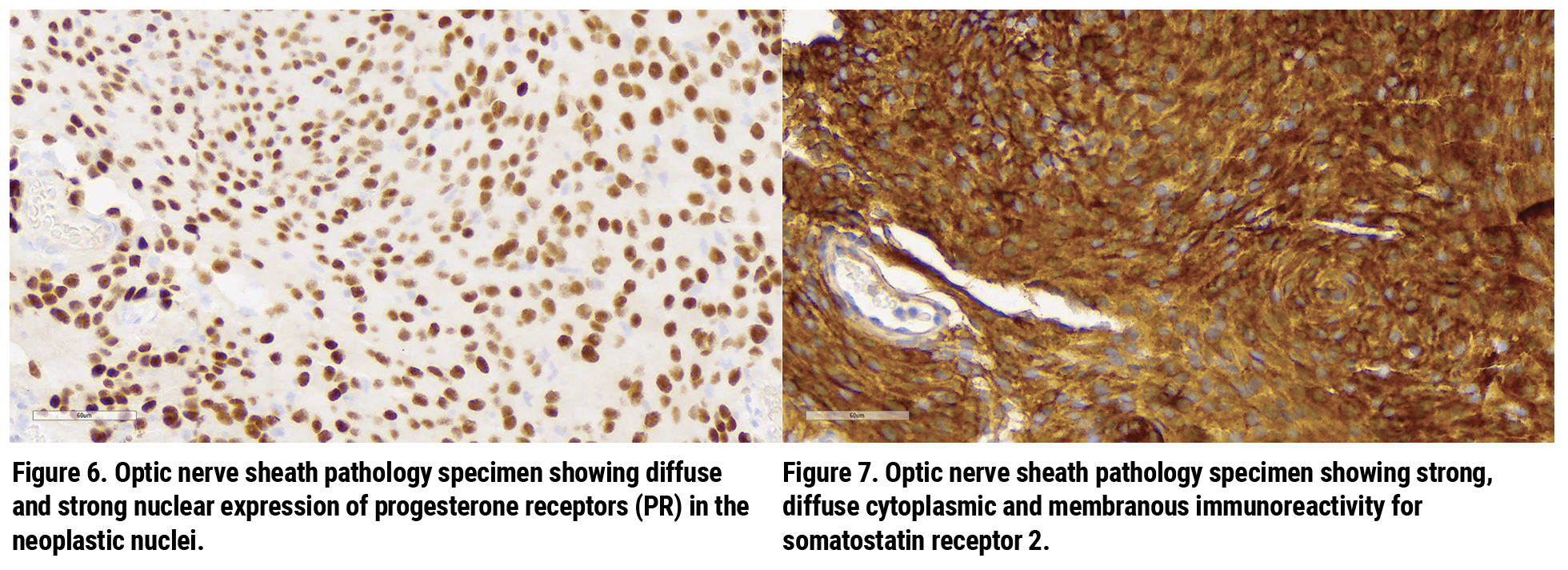

The pathological specimen showed neoplastic cells with minimally pleomorphic nuclei as well as eosinophilic cytoplasm in a whorled and nested syncytial arrangement (Figure 4); and lamellated extracellular calcifications (“psammoma bodies”) without appreciable nuclear atypia, mitotic figures or necrosis (Figure 5). There was diffuse and strong nuclear expression of progesterone receptors (PR) in the neoplastic nuclei (Figure 6) as well as strong, diffuse cytoplasmic and membranous immunoreactivity for somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2) (Figure 7). The pathological diagnosis was meningothelial meningioma, WHO Grade 1.

Several days after the biopsy, the patient returned for a follow-up visit at Wills Eye Hospital. Visual acuity without correction was 20/20 in the right eye and hand motions in the left eye. IOP was 20 mmHg OD and 23 mmHg OS. She had mild, <5 prism diopters of left exotropia with 90-percent abduction in the left eye; the exam was otherwise unchanged. She was referred for radiation therapy.

|

Discussion

Optic nerve sheath meningiomas comprise a third of all primary optic nerve tumors and originate from the meningothelial cells of arachnoid villi surrounding the optic nerve. Although ONSM are considered benign tumors, patients may experience progressive and permanent vision loss secondary to compression of the optic nerve and its blood supply.2 The tumors have a female predominance (female-to-male ratio is about 3:1) and typically manifest in the 4th or 5th decade of life.3 Generally considered a rare entity, ONSM encompass only about 1 to 2 percent of all meningiomas.2 Of note, there’s an association between ONSM and neurofibromatosis type 2.

Per Dr. Neil Miller in his 2006 paper4 regarding evaluation of ONSM, “the diagnosis of [optic nerve sheath meningioma] can be suspected in most cases from clinical findings and supported by the results of neuroimaging, obviating tissue biopsy in the majority of cases.” Overall, MRI is the preferred imaging modality for ONSM over CT; Ga-68 PET, however, may be helpful in uncertain cases.5 In fact, one 2012 study6 showed an “overall detection rate of 92 percent [by MRI] of the meningioma lesions that were found by PET/CT.” Primary findings on imaging include three distinct morphological patterns: tubular (“tram-track” pattern); fusiform; and globular. Calcifications on CT scan can increase the diagnostic probability of ONSM, although lack of calcifications doesn’t definitively rule out meningioma.

For cases of progressive optic neuropathy of uncertain etiology, optic nerve sheath biopsy is considered a last resort, as even subtotal optic nerve sheath biopsies limit the potential for visual recovery.7 Therefore optic nerve sheath biopsies may be more readily indicated for patients who already have severe vision loss. Other risks of optic nerve sheath biopsies include diplopia, abnormal eye movements, ptosis, numbness, eyelid/orbital deformity, infection, bleeding, inadequate specimen for diagnosis, CSF leakage and scarring. Given the inherent risks involved, all optic nerve sheath biopsies require careful counseling and shared decision-making between the patient and the physician.

Pathological findings of ONSM are similar to those of cerebral and spinal cord meningiomas although several variant forms exist including angiomatous, fibroblastic, meningothelial, transitional and psammomatous.8 Meningothelial meningiomas are the most common and may include findings of syncytial cells with indistinct cell membranes and eosinophilic cytoplasm; scant psammoma bodies; somatostatin receptor (SSTR) positivity; and diffuse, strong nuclear progesterone receptor (PR) positivity (particularly in low-grade meningiomas).8 Meningiomas are typically graded in accordance to the World Health Organization classification; grade 1 variants are benign while grade 2 and 3 variants are aggressive with malignant or metastatic potential.9

Treatment options for meningioma traditionally include observation, surgical excision or radiation therapy.10,11 Asymptomatic cases are observed, while surgical excision is reserved for blind eyes with severe proptosis, cosmetic concern or threat of intracranial spread.12 Radiation therapy is otherwise the standard of care for symptomatic ONSM.13 One retrospective case series by Rutgers’ University’s Roger Turbin, MD, and colleagues14 examining 64 patients with ONSM with at least 50 months of follow-up showed patients with radiation alone (compared to surgery alone, observation alone and surgery with radiation) demonstrated the best overall vision outcome during the study period. Other studies have similarly demonstrated the efficacy of radiation in vision preservation.15-17

Optic nerve sheath meningioma is a rare entity that presents with painless, progressive optic neuropathy. Patients are typically diagnosed based on clinical suspicion and imaging findings on CT, MRI and Ga-68 PET scans. Biopsy is reserved for ambiguous cases with severe vision loss. Treatment options include observation, surgery and radiation although the latter has been shown to have the best visual outcomes. In our case, the patient had an unusual, rapid progression of vision loss and ultimately underwent an optic nerve sheath biopsy showing low-grade meningothelial meningioma.

1. Galldiks N, et al. Advances in PET imaging for meningioma patients. Neuro-oncology Advances 5 2023;(Supplement 1):i84-i93.

2. Dutton JJ. Optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Survey of Ophthalmology1992;37:3.

3. Shapey J, et al. Diagnosis and management of optic nerve sheath meningiomas. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience 2013;20:8:1045-1056.

4. Miller NR. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of optic nerve sheath meningioma. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology 2006;26:3:200-208.

5. Rachinger W, et al. Increased 68Ga-DOTATATE uptake in PET imaging discriminates meningioma and tumor-free tissue. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2015;56:3:347-353.

6. Afshar-Oromieh A, Giesel FL, Linhart HG, et al. Detection of cranial meningiomas: Comparison of68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT and contrast-enhanced MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2012;39:9:1409-15.

7. Levin MH, et al. Optic nerve biopsy in the management of progressive optic neuropathy. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 2012;32:4:313-320.

8. Cai C. Meningioma. PathologyOutlines.com website. http://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/cnstumormeningiomageneral.html. Accessed June 3rd, 2024.

9. Marastoni E, and Barresi V. Meningioma grading beyond histopathology: Relevance of epigenetic and genetic features to predict clinical outcome. Cancers 2023;15:11:2945.

10. Eddleman CS, Liu JK. Optic nerve sheath meningioma: Current diagnosis and treatment. Neurosurgical focus 2007;23:5:E4.

11. Turbin RE Pokorny K. Diagnosis and treatment of orbital optic nerve sheath meningioma. Cancer Control 2004;11:5:334-341.

12. Kennerdell JS, et al. The management of optic nerve sheath meningiomas. American Journal of Ophthalmology 1988;106:4:450-457.

13. de Melo LP, Arruda Viani G, de Paula JS. Radiotherapy for the treatment of optic nerve sheath meningioma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2021;165:135-141.

14. Turbin RE, et al. A long-term visual outcome comparison in patients with optic nerve sheath meningioma managed with observation, surgery, radiotherapy, or surgery and radiotherapy. Ophthalmology 2002;109:5:890-899.

15. Narayan S, et al. Preliminary visual outcomes after three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for optic nerve sheath meningioma. International Journal of Radiation Oncology•Biology•Physics 2003;56:2:537-543.

16. Turbin RE, et al. Role for surgery as adjuvant therapy in optic nerve sheath meningioma. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2006;22:4:278-282.

17. Jeremic B, Pitz S. Primary optic nerve sheath meningioma: Stereotactic fractionated radiation therapy as an emerging treatment of choice. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society 2007;110:4:714-722.