Today’s technology for measuring the eye and formulas for determining IOL power before cataract surgery are far beyond anything available to surgeons 20 years ago. Nevertheless, results for many cataract surgery patients still fall outside the range of desirable outcomes. Here, experts share their experience and advice for making the most of biometry and formulas to improve your patients’ postop vision.

A Bevy of Biometers

Today, clinicians and researchers have numerous biometers available to them. Kenneth J. Hoffer, MD, FACS, a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the Jules Stein Eye Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, notes that he’s worked with every optical biometer since the first IOLMaster became available in 1999. “That includes the original IOLMaster from Zeiss, now referred to as the IOLMaster 500; Haag-Streit’s Lenstar; the Aladdin from Topcon EU; Nidek’s AL-Scan; Zeimer’s Galilei G6; Tomey’s OA-2000; the Pentacam AXL from Oculus; Movu’s Argos (now owned by Alcon); the IOLMaster 700 from Zeiss; and two that aren’t available yet: Heidelberg’s Anterion and Haag-Streit’s Eyestar 900,” he says. “We’re currently doing a comparative study of the Anterion, and we should have those results soon.

|

“All of these instruments do a good job, although there are a few differences between them,” he continues. “The competition in the field is probably a good thing. Zeiss, for example, might never have created the IOLMaster 700, moving from partial-coherence interferometry to swept-source OCT, if all of those other instruments hadn’t forced them to up their game. I do think offering swept-source OCT is an advantage; that’s now part of the IOLMaster 700, the Argos and the OA-2000, and it will be part of the Eyestar 900 and the Anterion. But any of these optical biometers will give you an accurate axial length measurement.”

Of course, getting an accurate measurement depends on more than just technology; the person taking the measurement has to know how to avoid potential pitfalls. Douglas D. Koch, MD, professor and chair of ophthalmology at Baylor’s Cullen Eye Institute in Houston, says the two biggest mistakes surgeons make are not verifying the quality of their data and not getting a separate measurement to verify its consistency. “The most significant errors made by optical biometry today involve measuring corneal power— in other words, the steep and flat meridians,” he notes. “Fortunately, the new biometers all give you a way to verify the quality of those corneal power readings. For example, you can look at the reflections of the LED mires on the cornea. Depending on how you set up the machine, they can even be printed out. Or, you can use the standard deviation of measurement as a guide. Warren Hill, MD, looked at data from the Lenstar; he concluded that a corneal power standard deviation greater than about 0.3 D is a red flag. Likewise, a meridian standard deviation of 3.5 degrees or more is also a red flag.”

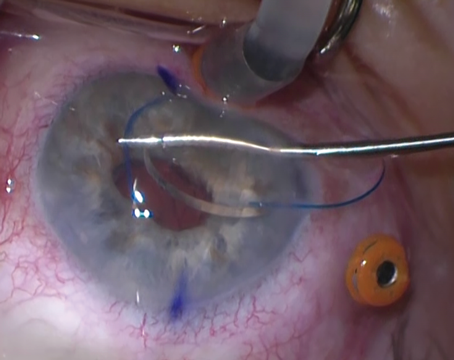

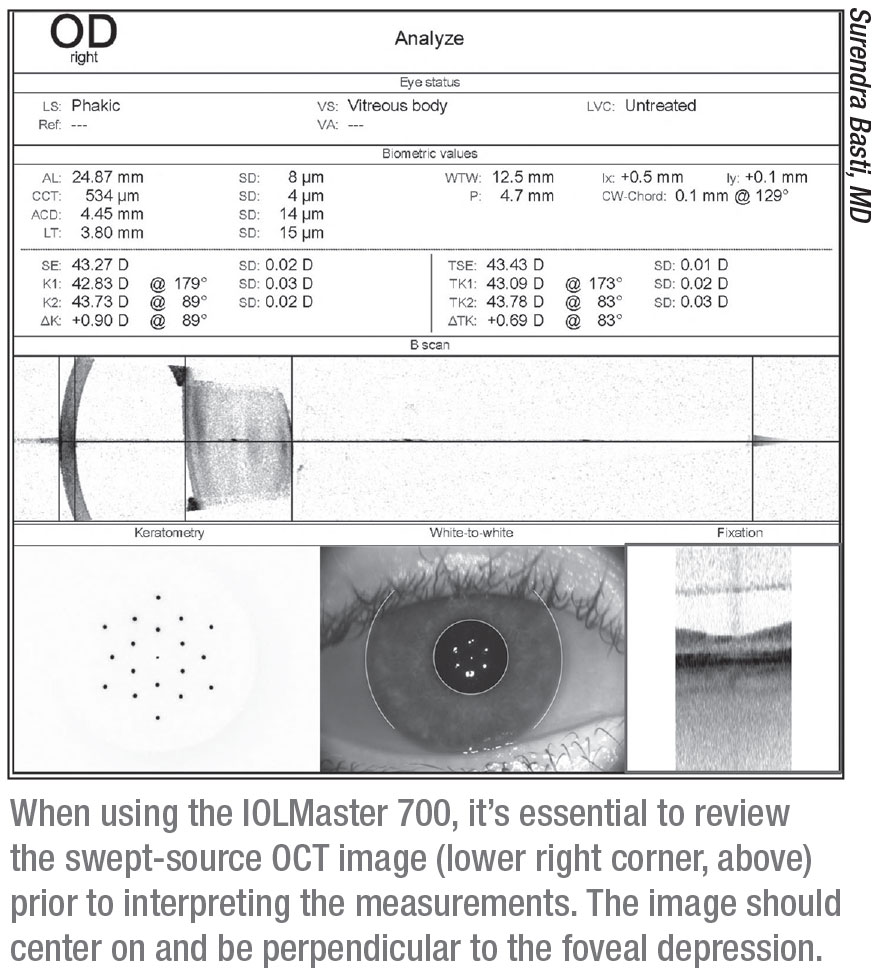

Dr. Koch points out that the IOLMaster 700 lets you look at a macular OCT scan to confirm that the measurement was taken correctly. (See example, above.) “The macular OCT scan lets you know if the patient was fixating adequately,” he explains. “You should see the umbo or the foveal pit clearly in the center of the OCT. If you don’t see a foveal pit, that means that either an epiretinal membrane or some other pathology is present, or the patient was not fixating correctly. That finding should lead to further investigation.”

Taking a Second Reading

Dr. Koch says that validating the biometry with a second reading is very important—especially if you’re considering a toric IOL. “Biometry can be wrong,” he points out. “I recall one case in which I took a Lenstar reading on a patient; it was about 43.3 D. The IOLMaster 700 gave us no readings at all for this patient, with obvious mire distortion on the printout. I went back and looked at a measurement I’d gotten with the Galilei when the same patient initially presented three months earlier. That measurement was 44.4 D—more than a diopter of disagreement, and with very different astigmatism measurements.

“Upon more careful examination, I found dry spots on the cornea that were present during the Lenstar and IOLMaster measurements,” he continues. “So, I treated the dry eye. When I repeated the Lenstar and IOLMaster measurements, they matched the Galilei measurement. The moral of the story is that validating your biometry with a second reading from another instrument can improve the quality and consistency of your measurements and avoid some poor outcomes.”

“If you don’t have a second device, you can at least measure the patient with the same device twice,” he adds. “Ideally, you should measure the patient on two different occasions, perhaps when the patient first presents, then on the preoperative visit. If you have to work with only one visit, get a measurement, have the patient sit back and blink, then get another.”

Surendra Basti, MD, a professor of ophthalmology and director of the cataract service at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, in Chicago, points out that it’s not practical to recommend that regular surgeons take multiple measurements of most patients. “There will always be surgeons who have access to a lot of devices, but those surgeons are few,” he says. “We need to focus on what’s practical. All surgeons have a biometry device, and almost all surgeons have a topography device. If you use those—along with immersion biometry in special cases—you should be fine.”

Of course, optical biometry may not work for every patient. “If the cataract is very dense, optical biometry may not be able to provide an accurate measurement,” notes Warren E. Hill, MD, FACS, medical director of East Valley Ophthalmology in Mesa, Arizona, who specializes in challenging intraocular lens power calculations and unusual anterior segment surgery. “In this case, immersion ultrasound is performed. If the patient is also a high-to-extreme axial myope with a posterior staphyloma, then an immersion vector A- and B-scan is required. This is a more sophisticated form of immersion biometry that measures the refractive axial length rather than the anatomic axial length.”

The Formula Factor

Perhaps the more daunting hurdle when aiming for an ideal outcome is plugging the biometric and refractive data into the most effective IOL power formula. When deciding which formula to use, a number of questions arise: Should you compare the results of multiple formulas? Should you use different formulas if the axial length is unusually long or short? And how should your choice be modified if your patient has had prior refractive surgery?

Dr. Koch says he still plugs the numbers into multiple formulas and compares the results. “I like to use the Holladay I, Holladay II, Barrett Universal II and the Hill RBF for my cataract patients,” he says. “Sometimes just seeing variability between the formulas’ results tells you that there may be something unusual about the biometry—a shallow anterior chamber, or a thick or thin lens, for example. If nothing else, you can tell the patient that you’ve run the calculations with four of the best formulas, and they’re not in total agreement. If that only helps in terms of educating the patient, that’s still a real benefit.”

“We know that traditional formulas tend to leave long eyes hyperopic,” says Dr. Koch. “That’s why Li Wang, MD, and I developed the Wang-Koch axial length modification to use with the Holladay I formula. You can also get good results in long eyes using the Barrett Universal II and the Hill RBF 2.0 formulas. Short eyes, under 22 mm, remain a challenge. We reported that the best formulas only gave us a little more than 70 percent of these eyes within a half diopter.1 Interestingly, the best two formulas we found in that paper were the Holladay I and Holladay II. But short eyes remain a problem that we really haven’t solved. You just have to use your best formulas and make your best guess. And in this situation, make sure the patient understands that the calculations may be inaccurate and he or she may be left with a refractive error, despite your doing your best.”

Dr. Hill says his preference is to use both the Barrett Universal and Hill-RBF formulas for all eyes. “When these two calculation methods agree, chances are very good that the refractive outcome will be as anticipated,” he says. “They also have the advantage of not requiring an axial length adjustment for very long eyes, and they perform very well for short eyes.”

|

One Formula Fits All?

As formulas have improved, many surgeons are feeling less need to check multiple formulas. Dr. Basti says he’s moving away from that practice. “Over the years we’ve become used to the idea of using different formulas for eyes with different axial lengths,” he notes. “My technicians still make a printout showing the results using four formulas: SRKT; Holladay I; Holladay II; and Barrett. However, I find myself relying almost entirely on the Barrett Universal II as my go-to formula. It does well, even in eyes with long or short axial lengths. It will almost certainly give you reliable results in almost every eye that you normally encounter.

“The one instance in which I think you would do well to look at multiple formulas,” he adds, “is in post-refractive-surgery eyes. Other than that, the idea of looking at multiple formulas is becoming less and less relevant.”

Dr. Hoffer is well-known for his IOL power formulas, from the original Hoffer formula that he published in 1974 to the Hoffer Q that became available in 1993. He notes that he was the first to suggest using different formulas for eyes with different axial lengths, in 1993. “Initially, most surgeons opted for finding the ‘best’ formula and using it on every eye,” he explains. “Our studies showed that the Hoffer Q formula worked better in eyes shorter than 22 mm, while it was equal to the Holladay I and the SRK/T in the medium axial length range, 22 to 24.5 mm. The Holladay I formula produced the best results in eyes between 24.5 and 26 mm, and the SRK/T was better in eyes over 26 mm.

“Today, we have formulas using all kinds of approaches, including artificial intelligence,” he continues. “The formula that’s currently getting the best results is a new one created by Jack X. Kane, MD, in Melbourne, Australia. I met him five years ago when he was a resident. His formula can be used by plugging in your numbers at his website; he’s following the Holladay principle of not publishing the formula’s details, an approach also followed by Barrett and many of the AI formulas. He also has a formula for use with toric IOLs. Given the study results I’ve seen, both from Dr. Kane and independent sources, I’d recommend using his formula, regardless of the axial length.”

Dr. Koch acknowledges that many surgeons today are simply relying on a single formula. “Many surgeons are just using the Barrett Universal II, which is a fabulous formula,” he says. “That’s fine. How well that will serve you depends on the patient’s expectations, and your expectations. I still think it’s valuable to have more than one formula’s result to look at.”

Dr. Koch adds that there’s another problem that may be hindering better outcomes, regardless of the formula being used. “We may not be inputting the most accurate information about the IOLs we’re implanting, with regards to asphericity,” he says. “That information will be necessary to refine those outcomes. Furthermore, there’s a slight variability in IOL powers. They’re supposed to be within 0.2 to 0.3 D of labeling, and I think the labeled powers tend to be very accurate, but it would be nice to have them refined even further.”

Prior Refractive Surgery

Dr. Koch says that when dealing with a post-refractive-surgery eye, a number of factors add to the challenge. “We’re still struggling with how to measure corneal power in this situation, and we don’t fully understand how previous refractive surgery affects the lens position calculation,” he explains. “In addition, the refraction is more nebulous in these eyes. They often have a somewhat multifocal cornea, so you may not be able to measure a clear endpoint. Twenty to 25 percent of these eyes end up outside the ±0.5 D range, and part of that may reflect the mushiness of the refraction and refractive error.”

Dr. Koch says that getting a good outcome in this situation is all about the formulas. “If you know the patient’s prior refractive history, the Masket, the Barrett and the Haigis L formulas work well,” he notes. “We’ve also had good success with the OCT formula that was developed for use with the RTVue, or the next generation of that device, the Avanti. Another interesting advance is being able to measure total corneal power. With the IOLMaster 700, for example, you can measure total keratometry. But even using that data, we’re still not breaking the 80-percent accuracy mark in our post-LASIK calculations—at least based on the written reports I’ve seen, as well as our own data.”

|

“When measuring eyes that have undergone prior refractive surgery, we rely heavily on standard biometry in the form of autokeratometry,” says Dr. Hill. “In addition, we often measure these eyes with topography and several other methods. A number of different post-refractive-surgery calculation algorithms have been developed for different devices, such as the Atlas topographer, the Pentacam and the RTVue. You can see how these are used on the ASCRS IOL calculation website (iolcalc.ascrs.org/wbfrmCalculator.aspx); for eyes with prior refractive surgery, a specific calculation method can provide the IOL power. My personal preference for both prior LASIK and RK eyes is the Barrett True K method.”

“If you have information about the eye before and after the refractive procedure, both the Barrett True K and the modified Masket formulas will do well,” says Dr. Basti. “In patients for whom you have no prior refractive information, the three formulas that do the best are the Barrett True K No History, the Haigis L, and the OCT-based formula. The OCT formula is useful because in post-refractive eyes the challenge is to estimate the true corneal power, and OCT can give you a very accurate measurement of that.”

When calculating the lens power for post-refractive eyes, Dr. Basti recommends using the ASCRS online calculator. “The ASCRS calculator asks you whether you have information related to how much refractive error was corrected with the prior refractive procedure,” he notes. “If you have that information, you put it in and one row of formulas lights up. Those formulas—the modified Masket and Barrett True K—will be most accurate in eyes that have had refractive surgery, if you have the preop information. If you don’t have that information, which often happens, another row of formulas lights up. That row includes the Barrett True K No History, the Haigis L and the OCT-based formulas.”

Dr. Koch says he’s hopeful that ray tracing may lead to a breakthrough. “Ray tracing does a better job of incorporating the variable corneal power within the central 3- to 4-mm zone than the other technologies,” he points out. “So far, it hasn’t outdone our best formulas, like the Barrett True K formula, but I think that’s because we’re not giving those ray-tracing formulas the best corneal power information. Thomas Olsen, MD, has developed a ray-tracing formula that’s shown some pretty good results. But I still don’t see anybody cracking the 80-percent barrier. Something is still missing.”

Strategies for Success

Surgeons offer these pearls for improving your outcomes:

• Know your biometry device well. “The better you know your biometer, the better your outcomes will be,” says Dr. Basti. “Every biometry device has recommendations from the manufacturer explaining how to optimize its use. In fact, one of the biggest mistakes surgeons make is not looking at the quality metrics of each measurement they take.

“For example,” he continues, “the IOLMaster recommends that the measuring beam go from the cornea to the fovea. The instrument gives you a swept-source-OCT image that shows the trajectory of the beam; it can confirm that the patient was looking at the correct spot and the measurement was taken accurately. In contrast, older versions of the IOLMaster such as the IOLMaster 500 let you see the light reflections on the cornea. If those reflections are crisp, that indicates that the measurement was reliable.”

“The best way to do biometry is to follow the validation guidelines that have been developed for each biometer,” notes Dr. Hill. “Validation criteria are available for both the Haag-Streit Lenstar and the Zeiss IOLMaster. [Dr. Hill assembled those criteria for both companies.] Surgeons need to avoid simply ‘button pushing’ and accepting everything at face value, because a measurement is only as good as our ability to know what it means. I’ve seen numerous cases in which a refractive surprise was traced back to some problematic aspect of the preoperative measurements that could have been identified if validation criteria had been applied. As carpenters like to say, measure twice and cut once.”

• If the axial length measurement is different between the eyes, check the measurement with immersion biometry. “Axial length is the biggest determinant of lens power, so even a small error can lead to a significant error in the lens power you pick,” says Dr. Basti. “A difference in axial length between the two eyes of more than 0.3 mm is a red flag. The eyes might simply be different, but there could be something else going on. In that situation it’s prudent to take another measurement using immersion biometry.”

• If implanting a toric lens, also use topography. “You can’t just use the astigmatism measurement taken by the biometer,” notes Dr. Basti. “With high astigmatism, a current optical biometry device will likely give you accurate an spherical power, but if you want to measure the astigmatism for a toric lens, it’s prudent to also use a topographer—especially a device such as the Pentacam, Galilei or Cassini devices—that can help factor in the posterior corneal astigmatism.”

Looking Ahead

Not surprisingly, the existing popular formulas continue to be improved and refined. “Later this year, version 3.0 of the Hill-RBF artificial intelligence IOL power calculation method will be released, first as an on-line calculator and later within the EyeSuite software of the Haag-Streit Lenstar,” says Dr. Hill. “This update is the culmination of one and a half years of work in cooperation with 44 study sites in 22 countries, with some of the world’s most accomplished cataract surgeons contributing data. Version 3.0 will now take into account the influence of the white-to-white measurement, lens thickness, central corneal thickness and gender.”

Dr. Hoffer is also preparing to release his latest update. “Later this year we’ll be releasing the Hoffer QS formula,” he says. “Refinements in this new formula are producing results on a par with the Barrett Universal II.”

Of course, no matter how good your biometry and formulas are, some patients will inevitably miss the intended mark. For those patients, new technologies that offer the possibility of changing IOL powers postop may save the day. “The FDA-approved RxSight light-adjustable lens is a neat technology,” notes Dr. Koch. “The problem is that it’s expensive. It’s not for the average patient. I’m cautiously optimistic about the upcoming technologies that use femtosecond lasers to modify almost any IOL that’s already inside the eye; they’ll allow us to implant affordable IOLs in our patients and tweak them postoperatively, if the patient desires. However, those options are in much earlier phases of development.” (For more on these technologies, see the feature "Adjustable IOLS: Lights, Lasers and Lock-ins.") REVIEW

Dr. Koch is a consultant for Carl Zeiss Meditec, Alcon, Johnson & Johnson Vision and Perfect Lens. Dr. Hill is a consultant for Zeiss, Haag-Streit, Alcon, Omega Ophthalmics, Optos and Veracity Surgical. Dr. Hoffer earns name trademark royalties from companies that include his formulas in their devices, for ensuring they’re programmed accurately. Dr. Basti has no financial ties to any device mentioned.

1. Gökce SE, Zeiter JH, Weikert MP, Koch DD, Hill W, Wang L. Intraocular lens power calculations in short eyes using 7 formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg 2017;43:7:892-897.