|

Despite ophthalmology’s desire to be based entirely in science, many “facts” that are widely accepted and used as a basis for important clinical choices are not necessarily accurate. Sometimes these “myths” are the result of casual observations that more careful clinical testing has failed to support. Some clinical choices, backed by little or no supporting evidence, have become accepted out of fear of not following the “community standard.” Sometimes they result from marketing claims that sound reasonable and simply haven’t been disproven.

“I think the occasional perpetuation of ‘myths’ is partly the result of the history of ophthalmology,” says Francis Mah, MD, who practices at Scripps Health System in San Diego. “This is one of those rare specialties that started off as apprenticeships. A lot of the other specialties sprang more from the academic centers, but many of the key thought leaders in ophthalmology are outside of academics. Much of what we’ve learned to do originated from someone trying something and finding that it worked pretty well; others in ophthalmology tried it and it became accepted. There is science behind a lot of it, but there’s also a lot that’s not science-based.

“For example, the surgeons who developed implantable lenses were not generally hard-core academicians,” he points out. “In fact, the academicians were the skeptics. And it was the high-volume surgeons and private practitioners who advanced phaco technology, while many of the academicians warned that this technology might ‘destroy’ eyes. Refractive surgery was also advanced outside of academic medicine and grudgingly accepted by the universities as more and more studies were produced and its validity was demonstrated. I think, as a specialty, that kind of experience has led to our willingness to accept and use a lot of unproven techniques.”

Challenging commonly accepted ideas is almost always controversial, and contradictory evidence is sometimes met with resistance. Nevertheless, it’s worth stepping back from time to time and looking carefully at some of the ideas and habits ophthalmologists have accepted that may not be supported by the evidence.

Here, a number of ophthalmologists share their thoughts on popular beliefs that deserve a careful second look.

Surgical Myths

Given the number of diseases and surgical approaches encountered in ophthalmology, it should be no surprise that some surgical methods and ideas are adopted without necessarily being evidence-based.

• An asymptomatic hole in the retina needs to be fixed. “When we spot a peripheral retinal hole, many of us react by deciding to prophylactically put some laser around it,” notes Uday Devgan, MD, FACS, FRCS, chief of ophthalmology at Olive View UCLA Medical Center and associate clinical professor at the UCLA School of Medicine in Los Angeles. “Although there’s not too much downside to doing that, any surgery involves some risk and expense. And a study conducted by Norman Byer, et al1, found that the typical, atrophic retinal hole can just be watched. You don’t, in fact, need to do anything about most of them.”

• Pars plana vitrectomies should only be performed by retinal surgeons. “Traditionally, pars plana vitrectomy has meant everything from membrane peeling to repairing retinal detachments,” notes Kenneth J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Utah Medical School and assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology at NYU Medical School in New York. “I agree that those surgeries should be performed by doctors who have been trained to do them. But pars plana vitrectomy has gained a lot of popularity in the past few years as an anterior segment surgical procedure in conjunction with cataract surgery, managing things such as vitreous loss at the time of cataract surgery, implantation of secondary posterior chamber lenses, implantation of anterior chamber lenses or managing dislocated lenses.

“Pars plana vitrectomy has many advantages over the traditional anterior vitrectomy that goes through the cornea,” he continues. “For example, it provides access to the vitreous base and allows the surgeon to remove the vitreous humor with a minimum of traction on the retina. It’s perfectly learnable by anterior segment surgeons, and it makes their surgeries safer and leads to better outcomes.”

Dr. Rosenthal notes that, in contrast, doing a vitrectomy through the anterior segment makes it very hard to get all of the vitreous out. “You’re pulling it up through the pupil,” he points out. “What you want to do is pull it back behind the pupil. The whole point of vitrectomy is to keep the vitreous humour out of the anterior segment and behind the iris. The best way to do this is to go in through the pars plana and allow the vitrector to pull it back into the posterior segment. Pulling it forward is less thorough and less predictable, and it’s harder to clear out residual cortical material.”

Dr. Rosenthal concedes there’s an element of fear involved for some anterior segment surgeons. “In my generation, even up until a few years ago, we were taught that the pars plana is the domain of retinal surgeons only,” he says. “Pars plana vitrectomy has been considered synonymous with repair of retinal detachment and things like membrane peeling or treatment of diabetic retinopathy. In reality, it’s simply a place in which you place the vitrectomy probe, and it’s very effective for anterior segment surgery. I think some surgeons believe it’s riskier than an anterior vitrectomy, but in my experience that’s not the case. In fact, the introduction of 25-ga. vitrectors has made the pars plana approach even more user-friendly for the anterior segment surgeon. These instruments are smaller, less invasive, and can be used in many cases without the necessity of suturing the sclerostomy.

“If you want to add this to your repertoire, of course, you need to be trained,” he acknowledges. “There are courses at the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery and Academy meetings that include wet labs where you can try out the pars plana approach. Interested surgeons may want to be mentored by someone who is adept at doing it; either scrubbing with them or observing them when they do the surgery. I don’t think it’s a hard technique for a trained, skilled surgeon to learn; there are just a few basic techniques that need to be adhered to.”

• Cystoid macular edema really doesn’t occur following cataract surgery today because of our advanced surgical techniques. “CME does still occur,” says Dr. Mah. “The rate is debatable, but it does occur. I’m concerned when I hear surgeons say that it doesn’t occur, so they don’t feel the need to use a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent. Why would any surgeon want to leave patients at risk for CME? Wouldn’t you want the best possible outcomes? Even if CME only happens in one case out of 100, that’s still a higher rate than endophthalmitis, and we use antibiotics and antiseptics to prevent that. So why wouldn’t you use an NSAID—proven to be efficacious at preventing CME—to improve your outcomes?”

• Preserving the recommended stromal bed thickness with a LASIK flap is critical. “When I was starting to perform LASIK in 1996, the recommended residual stromal thickness was 220 µm,” says Alan N. Carlson, MD, professor of ophthalmology and chief of the Cornea and Refractive Surgery Service at the Duke University Eye Center in Durham, N.C. “Over time the recommendation changed to 230 µm, and later 250 µm. The problem is that some surgeons take that number as a definitive boundary between what’s safe and what’s not. In reality, it’s an artificial number, and it may change again. There are lots of healthy corneas that underwent automated lamellar keratoplasty procedures years ago with beds that were substantially less than 250 µm, that did not go on to ectasia.”

|

Dr. Carlson notes that other factors may be more important than stromal bed thickness in the development of ectasia. “My own personal observation is this,” he says. “In my practice, and in patients referred to me, I’ve yet to find a post-LASIK ectasia patient who didn’t engage in significant eye rubbing, much like keratoconus patients. These are patients who have no family history of keratoconus or ectasia, or any predisposing factors. Every one I’ve encountered that has gone on to ectasia has been an eye rubber. So you shouldn’t have a false sense of security that 251 µm is somehow magically much better than 249 µm. It may have minimal courtroom significance, but it doesn’t have any clinical significance. On the other hand, how aggressively the patient rubs his eyes may be significant. It’s certainly an issue you can address if a post-LASIK patient shows signs of developing ectasia.”

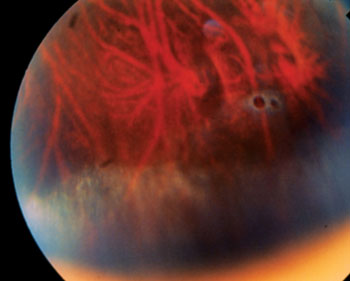

• You should never cause bleeding during surgery if you can help it. “Actually,” says Dr. Devgan, “incisions in avascular tissues such as the cornea heal much more securely if a tiny bit of blood is present in the incision. For example, if you barely nick the limbal vessels as you make the corneal incision for phaco, the healed incision will be very strong and difficult or impossible to reopen later.” (See photo, above.)

• Liquid betadine on the eye and face is optimal for disinfection. “When we prepare a patient for surgery and the patient has a betadine scrub, the betadine is most effective during the drying process rather than in its wet form,” says Dr. Carlson. “It’s the drying process that accentuates the antiseptic effect.”

Medical Therapy

With a huge number of medications in use, and ideal clinical trials being prohibitively expensive, many popular ideas about using medications are open to question.

• The newest antibiotic is better. “In the field of infectious disease, a subspecialty of internal medicine, when a new antibiotic comes on the market infectious disease subspecialists try to establish the optimal circumstances for using that medication,” notes Dr. Carlson. “Should it be used for every case of antibiotic prophylaxis? What pathogens does it treat most effectively? Is it such a good antibiotic that it should be held back and used less often in order to slow down antibiotic resistance?

“The pharmaceutical industry has led us to believe that they’re always working on the next generation antibiotic, and the next generation is always better,” he continues. “That’s not necessarily the case. For example, a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone is not as good as a third-generation one with respect to pseudomonas, a common infection associated with contact lens wear. So even though you’ve gained a lot of coverage in areas that were not effectively treated with third-generation agents, you shouldn’t assume that the next generation will be more effective in every situation.

|

• Generic and brand name drugs are the same. “It’s well documented that the only FDA equivalency requirement for a generic drug is that the drug has the same active ingredient(s), dosage form, route of administration and strength,” notes Dr. Rosenthal.2 “The devil is in the details. There could be different solubilizers, the pH could be different, and so forth, and as a result the efficacy and side effects may be different. The only consistent product is the brand-name product.

“For example,” he continues, “in postop treatment for inflammation following cataract surgery, excessive, unanticipated postoperative inflammation can be disastrous and cause permanent damage to the eye and vision. I avoid the use of generic topical steroids and NSAIDs in this situation because I know that steroids and NSAIDs are essential for best outcomes, and I can’t rely on a generic medication to have the same potency, efficacy and safety as its brand-name equivalent.”

Dr. Rosenthal admits that he frequently runs into problems with insurance coverage when using brand-name prescriptions in this situation. “The insurance companies want an explanation as to why I’m prescribing the brand name drug,” he says. “They want us to use generic equivalents, or prove that the generic failed first. My answer is that we don’t want cataract surgery to fail because of inadequate treatment. We only have one chance to do it right.” (For more on differences between generic and brand name drugs, see “Changing Treatment Paradigms in Glaucoma,” on p. 58.)

• Antibiotics can be used like antiseptics. “I think ophthalmologists, more than any other subspecialty, have forgotten how antibiotics work,” says Dr. Carlson. “We often use antibiotics as though they were antiseptics, which work to kill an organism on contact. Although there are many different antibiotic mechanisms, the principle behind most antibiotics is related to interfering with the process of replication, where the effect is either static or cidal. Whether an antibiotic is successful is a function of the antibiotic’s mechanism of action, the concentration and the amount of time it’s in contact with a susceptible replicating organism.

“Often when we use antibiotics during surgery, we don’t have a sense of how long the duration of effect is,” he continues, “or how effective it may be against organisms that are either retained in the eye at the completion of surgery or get into the eye at a later date as a result of a wound leak or the patient rubbing the eye. This is particularly the case when we consider the limitations of adding antibiotics to the intraoperative infusion. Clearly, both antibiotics and antiseptics have important contributions to make, but it’s really important to understand that these are different treatments with different effects.”

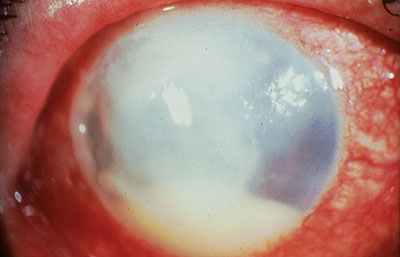

• Steroid drops are contraindicated in patients with rheumatoid melt. “Many ophthalmologists believe this,” says Dr. Carlson. “It’s even in textbooks, but I think it’s based on potentially wrong interpretations of case reports. Nearly 50 years ago, there were anecdotal reports of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmune keratitis with peripheral non-infectious keratitis, often referred to as corneal melting. They were given corticosteroid drops and went on to perforation. I think that led to the conclusion that the steroid drops were responsible for accelerating the process that led to perforation and are therefore contraindicated in that scenario. Doctors even joked that we needed to make sure the caps on the corticosteroid drop bottles were tightened so even the fumes couldn’t get to these patients!

“I believe the misinterpretation resulted from corticosteroids reducing swelling and interfering with the reparative process,” he continues. “When the patients went on to perforation, observers concluded that the steroids were responsible for making the patient worse. However, my personal assessment and review of this topic suggests that this conclusion may not be universally correct. Yes, steroids interfere with the reparative process, but that’s different from actually causing the disease process to progress. For example, it’s not the same as prescribing a topical steroid for a patient with fungal keratitis, where you clearly are at risk of making matters worse.

“Today it’s recognized that patients with rheumatoid arthritis that leads to active inflammation and a so-called ‘melt’ in the cornea need systemic therapy rather than simply topical therapy,” he adds. “But I do think there’s an appropriate time to add topical corticosteroids in patients with a non-infectious autoimmune melt.”

• Dry eyes mean insufficient tear production. “I suspect the vast majority of ophthalmologists are still giving dry-eye patients artificial tears and punctal plugs and Restasis,” says Dr. Carlson. “Although this can be helpful for many patients, we’re still under-recognizing the role of the lid margin, the meibomian glands and an inadequate lipid layer contributing to tear film instability. I am a consultant for TearScience, which makes devices designed to evaluate and treat meibomian gland dysfunction, but my experience with those devices has convinced me that MGD really is a significant part of the problem for many, many patients. The report from the Tear Film and Ocular Surface workshop came to the conclusion that MGD may even be the most common cause of dry eye, and I believe it.”

• A red eye post-surgery that’s slow to heal should be treated for herpes simplex. “At least a dozen times a year I see a patient who is on topical herpes medication after some type of eye surgery, because the eye was red and slow to heal and eventually developed an epithelial defect that didn’t get better,” says Dr. Carlson. “The thinking is that surgical trauma, stress and postoperative topical corticosteroids have precipitated HSV keratitis without any pre-existing episodes. In fact, adding the topical anti-viral medication often contributes to ongoing redness and a further slowing of the healing.

“A better approach is to get a more thorough history for herpes simplex and consider culturing for it,” he continues. “In some patients, it might make sense to get a herpes simplex antibody titer. Even though a positive titer doesn’t prove that an infection is present, a negative titer can help rule it out and tell you to look for something else—saving the patient from being subjected to a toxic epithelial agent.”

• When treating for herpes epithelial keratitis, treatment should continue until symptoms are gone. “Seven to 10 days of treatment is generally enough,” says Dr. Mah. “In most cases HEK will go away by itself in that amount of time even without treatment, unless there’s some other issue with the patient such as immunosuppression. I’ve seen doctors keep HEK patients on high therapeutic dose topical agents for weeks or even months at a time. The older generation anti-viral trifluridine (Viroptic) was pretty toxic; the eye would turn red and you’d get epithelial toxicity. Many times, it was assumed to be the herpes epithelial keratitis persisting. In fact, it was medicamentosa; discontinuing the medication would have resolved the epitheliopathy and periocular inflammation.”

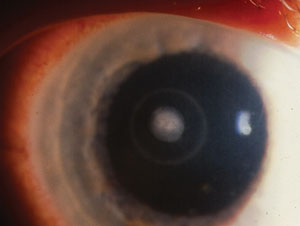

• A ring infiltrate in a contact lens wearer is pathognomonic for acanthamoeba infection. “Although this pathogen may be the cause of this problem, many patients have been getting shotgun treatments for Acanthamoeba whenever a ring infiltrate is discovered,” notes Dr. Carlson.

“Actually, a ring infiltrate can be caused by a number of bacterial infections, including Bacillus cereus; Pseudomonas aeruginosa; and Streptococcus organisms. We shouldn’t forget this and miss an opportunity to identify other causative organisms with an appropriate culture and confocal microscopy.

|

“Furthermore,” he adds, “the ring infiltrate in the cornea is often referred to as a Wessely immune ring. That’s inaccurate, because the process causing the infiltrate in the eye is completely different from the process that causes a Wessely immune ring to occur on an Ouchterlony plate in a laboratory, although it may have some resemblance to that process. In the cornea, the ring is formed by a white cell response to antigen; in the Wessely immune ring, antibodies are precipitating antigen. Understanding that ring-like inflammation in the cornea may not represent Acanthamoeba stresses the importance of culture, Gram stain and diagnostic evaluation to better guide therapeutic decision-making.”

Antibiotics & Cataract Surgery

Almost every cataract surgeon today treats cataract patients with both topical steroids and antibiotics for several weeks following surgery. But while there is considerable clinical evidence that steroids serve an important purpose, the same can’t be said for the use of topical antibiotics.

“The only thing that’s been proven to reduce the rate of endophthalmitis is a drop of povidone iodine before surgery,” says Dr. Devgan. “Using antibiotics after surgery is not only off-label, it’s anecdotal. The argument is that it’s too hard to do a trial to test this, because the rate of endophthalmitis is so low—one out of 3,000 to 5,000 patients. You’d have to do a huge study, and it would be too big an undertaking to be worth it.

“Meanwhile, it’s worth noting that on some charity mission trips, antibiotic drops following cataract surgery are not feasible,” he continues. “Furthermore, this practice is not commonly done in other fields of medicine. It’s very unusual for a surgeon to give you antibiotics after almost any other procedure as a preventive measure. But because so many ophthalmic surgeons do it, it’s become seen as ‘the standard in the community.’ Meanwhile, that raises the question: If one in 5,000 individuals gets endophthalmitis, are we needlessly treating 4,999 patients with antibiotics? Should we treat 99.9 percent of the population to help the remaining 0.1 percent? In any case, even using antibiotics after cataract surgery has not eliminated endophthalmitis completely.”

|

He notes that the lack of evidence extends to the question of dosage and length of treatment. “I’m not aware of any studies that suggest when to start or stop the antibiotics in relation to cataract surgery,” he says. “I’ve heard of people using antibiotics for three to six months following routine, uncomplicated cataract surgery. I think that might be excessive.” So how do surgeons decide what to do? “A lot of it, I think, goes back to where and how we were trained,” he says. “I suspect most of us do whatever we were doing in residency. Again, very little science is associated with it; most of us just

adopted the techniques we learned from our mentors.

“Once we’re practicing, I think changes are most likely to occur when a patient has a problem,” he continues. “For example, if you encounter a postop infection, you suddenly start looking at what you’re doing, reading the literature and talking to other people who may be considered experts. Beyond that, I think most changes in protocol that happen happen because of where we practice and what the other doctors in the area are doing. In other words, if a lot of people are giving preoperative antibiotic drops for three days before cataract surgery, you’ll probably adopt that so that you’re not departing from the norm. You don’t want to be lacking in the standard of care, even though there may not be a lot of evidence for it.”

“The question as to whether topical antibiotics are necessary post-cataract surgery still remains unanswered,” agrees Dr. Rosenthal. “It may be true that they make a difference, but it’s almost impossible to prove. That’s why there are no FDA-approved antibiotics for this purpose. Instead, they’re approved for bacterial conjunctivitis.”

Part of the reason this is an issue is that in addition to being supported by, at best, limited clinical data, using antibiotic drops after cataract surgery is a burden on patients, both financially and in terms of their time and effort. “I’ve been concerned about the high cost of postop drops for my patients for a very long time now, and I’ve been working to find a solution,” says James P. Gills, MD, founder and director of St. Luke’s Cataract & Laser Institute, and clinical professor of ophthalmology at the University of South Florida. “For about one year now I’ve been eliminating postop drops for my standard cataract surgery cases by giving patients intraocular antibiotics and steroids along with a 1.2 cc sub-Tenon’s retrobulbar injection of Kenalog at the time of surgery. This regimen eliminates the need for postoperative drops, saving the patients approximately $400 and freeing them from the inconvenience of the postop drop schedule. The results have been the same as for patients with a full postop drop regimen. Furthermore, as an added benefit, I’ve seen fewer rises in IOP postoperatively.”

Managing Patients

Questionable beliefs extend to patient management as well.

• It’s crucial to have a preoperative history and physical clearance by the primary-care doctor before cataract surgery. “The largest study relating to this, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, the number one journal for doctors of internal medicine, showed it made no difference,” says Dr. Devgan.8 “In a long procedure such as heart, lung or brain surgery, you’re giving the patient a large amount of anesthesia. In that situation, there certainly is a need to get the patient’s health fine-tuned—especially with an elective procedure such as hip-replacement surgery. Those procedures put major stress on the body.

But cataract surgery is not such an involved and detailed procedure, and it doesn’t require a large amount of anesthesia. It can take as little as five minutes, and there’s zero blood in most cases. In this study, as long as patients were in reasonable health to begin with, doing the whole preop physical, EKG, history, blood test, chest X-ray and so forth with the patient’s internal medicine doctor was of no benefit.

|

“The reality is, what many of us undergo at the dentist is far more invasive,” he adds, “and the dentist doesn’t require a physical beforehand.”

• Keratoconus patients rub their eyes because of allergies. “It’s true that keratoconus patients are more likely to have allergic eye disease, but it’s a myth that their excessive eye rubbing is entirely a consequence of allergies,” notes Dr. Carlson. “As noted in my article in the October, 2009 issue of Review, these patients rub their eyes in a unique, aggressive manner. There are 15 specific differences between purely allergic and purely keratoconus eye rubbing. For example, rather than rub their eyes for 12 to 18 seconds like an allergic patient, patients with keratoconus may rub their eyes nonstop for three to five minutes, and they may do a very deep, hard, aggressive rub. The data is looking stronger that this habit is accelerating their downhill progress.

“It’s possible to have both keratoconus and allergies, of course,” he adds. “Patients that have both often exhibit both types of eye rubbing. But it’s important to make this distinction, because an ophthalmologist who doesn’t know about this may treat this patient for an allergic component and miss the fact that the eye rubbing won’t be stopped by treating for allergies—and it may be a factor in the keratoconus becoming worse.”

• Patients should be checked frequently after cataract surgery. “How many postop visits does a cataract patient need?” asks Dr. Devgan. “At the county hospital where I work with residents, we used to have cataract patients return for five or six post-op checkups, usually at day one, day three, week one, week two, month one

and month two. At just 1,000 cases per

year, this amounts to at least a few thousand unnecessary follow-up visits.

“We finally decided to only do follow-up visits at points at which an intervention might be called for,” he continues. “Now we’ve cut follow-up visits down to three. We see patients on postop day one because the incision could be leaking, the pressure could be high, the lens could have slipped or there could be a retained piece of cataract in the eye. We see them at one to two weeks post-surgery, because the biggest studies show that patients with endophthalmitis present around postop day nine to 11. Six weeks post-surgery also makes sense because that’s a good point to dilate the eyes, examine the retina and see if a YAG laser treatment is necessary. Residents often aren’t as meticulous at cleaning the posterior capsule when they perform surgery because they’re afraid they’ll pop it, so their patients need to be checked for this.

|

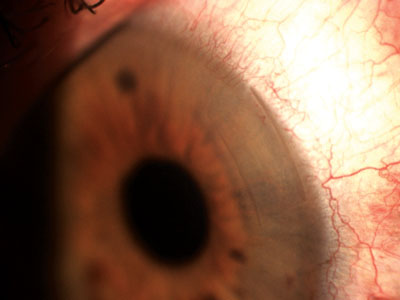

• Extended-wear contact lenses are safe. “Because this type of contact lens is FDA-approved for extended wear, both doctors and consumers tend to assume there’s no significant risk involved in using them,” says Dr. Carlson. “Actually, I am unaware of any contact lens that can be worn overnight that has been proven to not increase your risk of getting microbial keratitis. In the contact lens-associated microbial keratitis study, wearing contact lenses overnight increased the risk of infection fifteenfold; the only other risk factor that was even marginally significant was the patient being a smoker. Since that time, I’m not aware of any contact lens being developed that’s been proven to not elevate the risk of infection.”

A Reason for Doing What You Do

Dr. Mah believes the fundamental principle here is that it’s a good thing to have a reason for doing what you’re doing. “If a doctor says he’s using antibiotic drops for a week prior to surgery, I’d like to know why he’s doing that,” he says. “I don’t know that any evidence supports that, and potentially you’re contributing to antibiotic resistance. But if you’re doing it because you want to teach the patient to use the drops correctly, then at least you have a reason. There are studies that show that if you have a clean ocular surface, using antibiotics for three days before surgery clears out the normal flora better than using them only one day before. If that’s your protocol and that’s your reasoning, great. Go with that.

“My advice,” he concludes, “is to stop and step back a little bit and think about what you’re doing in day-to-day practice. Don’t just say, ‘Well, that’s how everybody does it,’ or ‘That’s how I was taught to do it.’ Have a real reason for what you’re doing.” REVIEW

1. Byer NE. Prognosis of asymptomatic retinal breaks. Arch Ophthalmol 1974;92:3:208-210.

2. From FDA regulations. See: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/informationondrugs/ucm079436.htm.

3. Allen HF, Mangiaracine AB. Bacterial endophthalmitis after cataract extraction. A study of 22 infections in 20,000 operations. Arch Ophthalmol 1964;72:63-78.

4. Allen HF, Mangiaracine AB. Bacterial endophthalmitis after cataract extraction. II. Incidence in 36,000 consecutive operations with special reference to preoperative topical antibiotics. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1973;77:OP581-588.

5. Jensen MK, Fiscella RG, Moshirfar M, Mooney B. Third- and fourth-generation fluoroquinolones: Retrospective comparison of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery performed over 10 years. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008;34:9:1460-7.

6. Moshirfar M, Feiz V, Vitale AT, Wegelin JA, Basavanthappa S, Wolsey DH. Endophthalmitis after uncomplicated cataract surgery with the use of fourth-generation fluoroquinolones: A retrospective observational case series. Ophthalmology 2007;114:4:686-91.

7. Jensen MK, Fiscella RG, Crandall AS, Moshirfar M, Mooney B, Wallin T, Olson RJ. A retrospective study of endophtalmitis rates comparing quinolone antibiotics. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;139:1:141-8.

8. Schein OD, Katz J, Bass EB, et al. The value of routine preoperative medical testing before cataract surgery. N Engl J Med 2000;342:168-75.