The optic nerve, all 1.75 inches of it, has long challenged science to find the reasons it can become inflamed. In 1890, 40 years after the ophthalmoscope arrived on the diagnostic scene, physician A.A.

Hubbell observed in the Buffalo Medical Journal that “[Optic] neuritis, as a rule, presents nothing which distinguishes its cause.” 1

And while technologies now exist to help pinpoint why a patient has optic neuritis, physicians are still vexed by the nerve’s diagnostic one upmanship. In small anatomic regions, “Pathology is more difficult to visualize, such as the optic nerve and the brainstem,” noted one paper in 2019.2

Today, the spectrum of optic neuritis subtypes includes other co-associated inflammatory disorders of the central system, besides multiple sclerosis. The use of OCT and MRI and the discovery of serum biomarkers have helped to provide accurate diagnoses of other causes of optic neuritis, including myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein associated antibody (MOGAD) and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD). Treatments are now available for these disorders.

But most good news has a price tag.

In interviews with prominent neuro-ophthalmologists, who discuss these recent diagnostic and treatment successes, they interject a poignant caveat: Therapeutic success for optic neuritis requires rapid diagnosis and treatment—days, not months—to save the patient’s sight.3 Here, they share their tips for ferreting out the cause.

A Primer

|

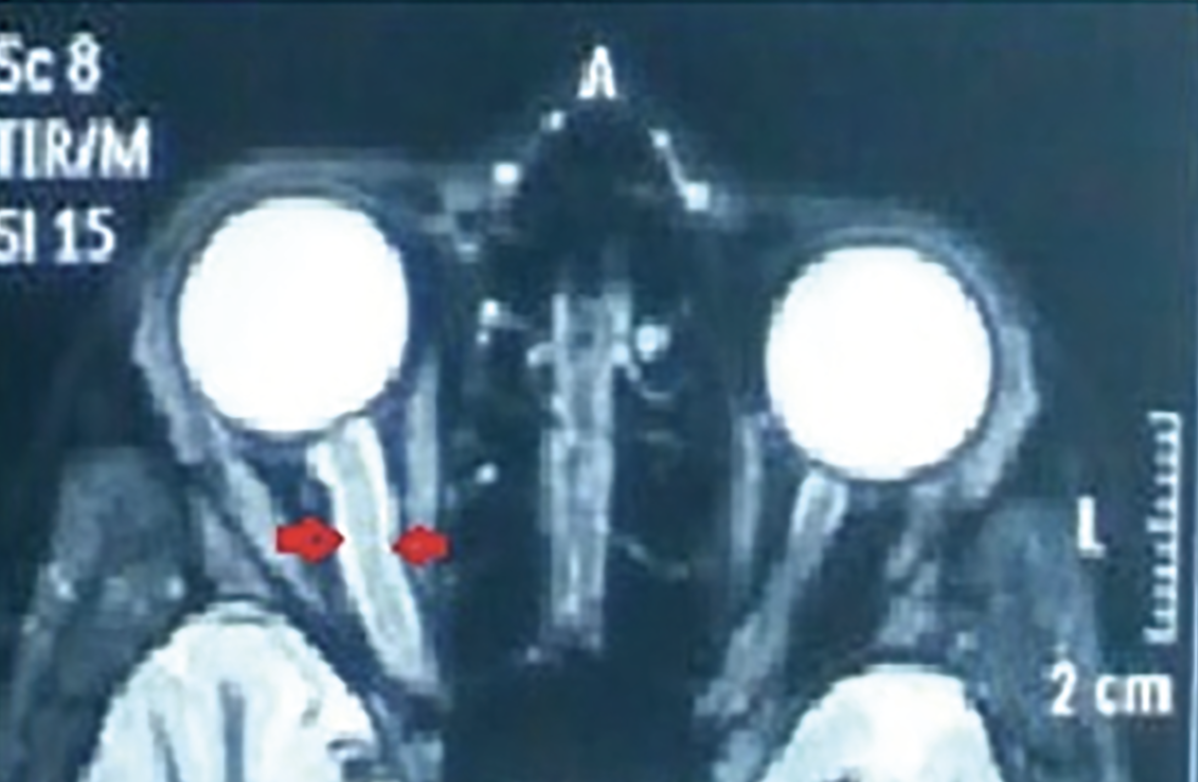

| Axial T 2 MRI scan showing swelling of retrobulbar intraorbital segment of optic nerve of the right eye. (Gupta A. A Case of Unilateral Optic Neuritis in a 13 Year Old Boy. J Ophthalmic Clin Res 2019;6:055.) |

Optic neuritis is a syndrome, not a disease. It’s a common diagnosis; the prevalence is 115 per 100,000 persons in both the United States and the United Kingdom. The optic neuritis associated with multiple sclerosis appears more in women, Caucasians and those who live at high altitudes.4,5

The ON associated with idiopathic and multiple sclerosis usually involves:

• subacute vision loss;

• just one eye;

• pain that often worsens with eye movement;

• a relative afferent pupillary defect in cases of unilateral or asymmetric optic nerve involvement; and

• dyschromatopsia from the affected eye.

Optic neuritis can manifest in autoimmune conditions of the central nervous system, infections and systemic diseases, such as:

• Multiple sclerosis;

• MOGAD;

• NMOSD;

• CRION, or chronic relapsing inflammatory optic neuritis;

• GFAP, or glial fibrillary acidic protein antibody-associated astrocytopathy;

• Tuberculosis, syphilis and cat-scratch fever;

• Sarcoidosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

The optic nerve bridges the outside world to the brain, and in doing so places its diagnostic and clinical jurisdiction, from the vantage point of specialty medical training, into the hands of the neuro-ophthalmologist. But, because it is the eye that becomes symptomatic, first-line health-care providers are those whom a patient generally sees. “A person presents with pain in the eye and loss of acuity,” says Robert C. Sergott, MD, chief of the Neuro-Ophthalmology Service at Wills Eye Hospital. And the place of presentation is often in the emergency department, says Nancy J. Newman, MD, the LeoDelle Jolley Chair of Ophthalmology at Emory University School of Medicine.

Unfortunately, the ER may lack diagnostic tools, such as OCT, to identify optic neuritis or exclude other causes of vision loss, says Fiona Costello, MD, FRCPC, a professor at the Cumming School of Medicine Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Calgary.

A patient with NMOSD might develop rare symptoms such as inappropriate sodium control or protracted hiccups, nausea or vomiting before the optic neuritis, says Jeffrey Bennett, MD, PhD, the Gertrude Gilden professor for Neurodegenerative Disease Research at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. “You can imagine if someone shows up with nausea and vomiting in the ED, they will call gastroenterology. And, unless someone is knowledgeable, the next attack [of NMOSD] could be devastating,” he says.

So, yes, misdiagnosed cases of optic neuritis exist.6 Referrals are important. But to get a referral in time to save a patient’s sight, should the cause of the optic nerve’s inflammation be vision robbing? Not easy, says Dr. Newman: There are just not enough neuro-ophthalmologists out there. At last count: fewer than 700, nationwide7—which increases the urgency to get the diagnosis right on the patient’s initial visit.

|

Background

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial compared patients with newly developed optic neuritis treated with either oral prednisone, IV methylprednisolone or placebo. They found no long-term benefits to visual outcomes and that those with optic neuritis recovered their sight, with or without medication.8

“We used to say that there’s no urgency to treat,” says Dr. Sergott. “Ophthalmologists and neuro-ophthalmologists assumed ON was synonymous with MS. MS is a very serious disease, but for patients with ON and MS, their vision will improve quite well without steroids.”

That all changed when biomarkers for two CNS-attacking autoimmune diseases were discovered in the mid-2000s.

|

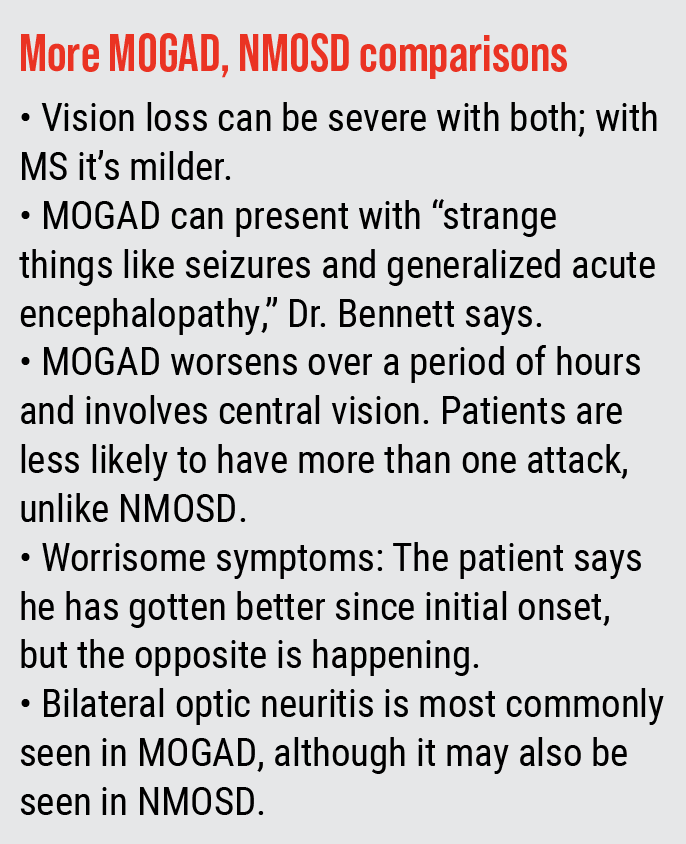

In NMOSD, patients with this disease are anti-aquaporin-4 antibody-positive. The disease moves quickly. These patients don’t have “a lot of time to wait [for treatment],” Dr. Sergott says. “They will get irreversible damage that they can’t repair.” In MOGAD, the immune system attacks a protein called the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, found on the CNS’ sheath. MOGAD also affects the optic nerves and brain. These patients also require treatment within a week after symptom onset to limit the severity of the attack.

NMOSD may cause irreversible injury to the optic nerves and spinal cord. According to Dr. Sergott, NMOSD is “the real big one” with a “devastating natural history.” A quarter of patients have lasting disability after the initial attack, and one-third of patients given steroids show improvement, but in time “these patients may have paralysis from the neck down.”

“What experts know now is that ON is an optic emergency,” says Dr. Bennett. And the point, says Dr. Sergott, is to let all other health-care providers know it too.

From Specific to Idiopathic

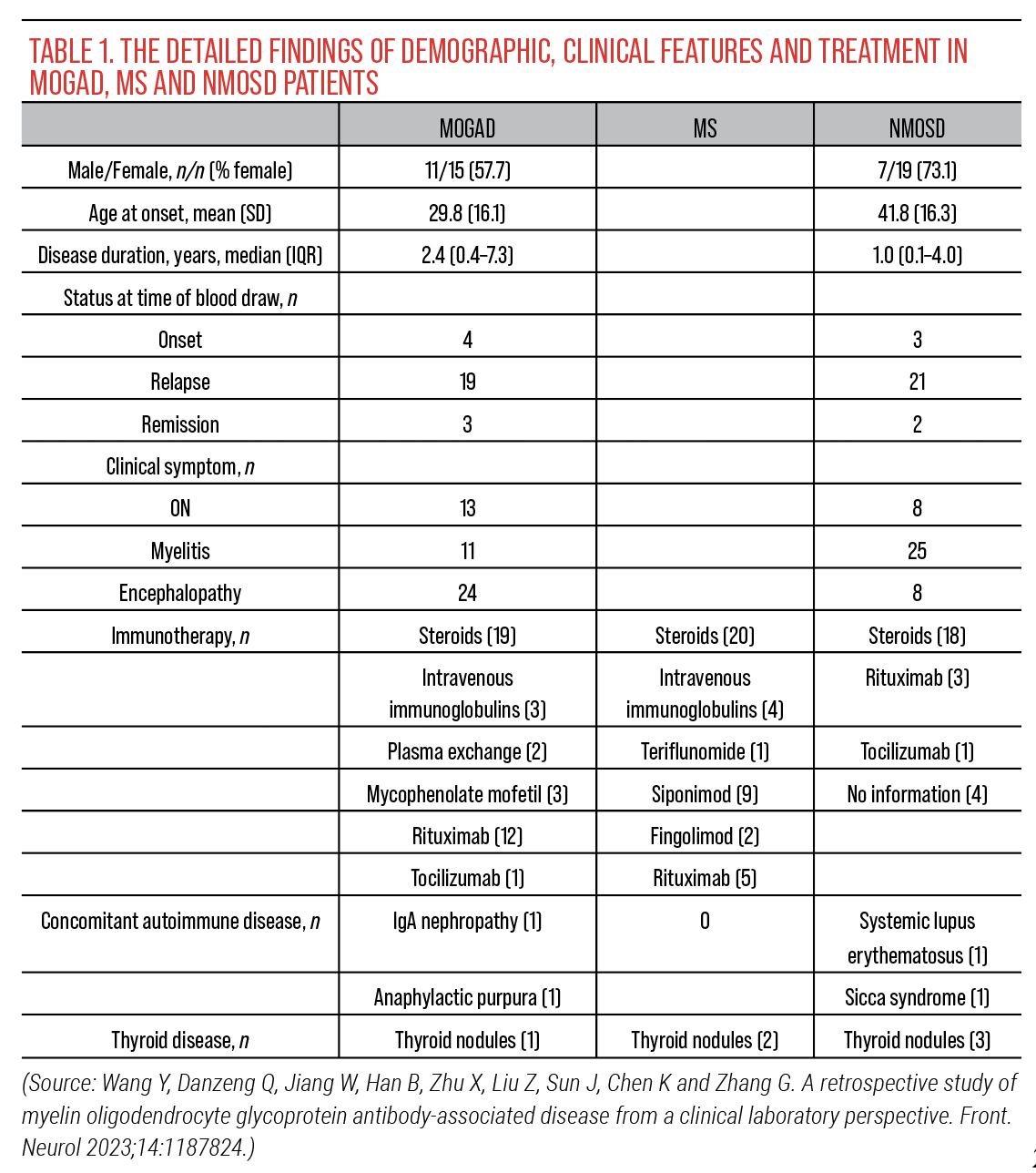

The signs and symptoms of ON’s causes often overlap with each other. One recent study found that, due to the poor specificity of the clinical manifestations of MOGAD, it can easily be misdiagnosed as MS, NMOSD or other demyelinating diseases.9

Moreover, the known disorders or diseases affecting the optic nerve only comprise about 60 percent of actual diagnoses. In the United States “MS accounts for half of what will come through the door, the other two [MOGAD and NMOSD] are 6 percent,” says Dr. Bennett. The “dreaded idiopathic” diagnosis eludes cause but often has significant effects.

|

| Optic neuritis can be visualized through fundoscopy, which may indicate the presence of multiple sclerosis. (Guier C, Stokkermans T. Optic neuritis. StatPearls 2024 [internet].) Photo: S. Bhimji, MD. |

That 50-percent figure represents the patients who are referred by ophthalmologists, primary care physicians and ED visits. A study published in 2018, based on blood samples of 177 patients enrolled in the 1992 Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial, found three patients were positive for MOG-IgG and none had NMOSD.10 The trial’s design likely impacted these findings: It was U.S.-based, restricted age to those 18 through 46, and excluded those with bilateral optic neuritis, which is a characteristic of NMOSD and MOGAD.11

The discovery of NMOSD and MOGAD led researchers to think they could learn more about differentiating MS, but that didn’t happen, Dr. Bennett says. At this time, it’s likely some patients are under the MS umbrella because they mimic a pattern of distribution and progression of activity that fulfills current MS criteria. But, “the risk of MS is heightened by a whole lot of individual mutations and genes. With about 250 genes implicated in that risk, “the [odds of the] impact of one gene remain rather low.”

History

Dr. Costello says the keys to diagnosis are listening to your patient and knowing what to ask. In the case of optic neuritis, she considers who the patient is, how the patient lost vision, what co-associated medical issues they may harbor, and where they live to determine what subtype she may be treating.

Other questions:

• How did the patient notice vision loss? Was it sudden, gradual, did it progress over hours to days?

• What is the pain like? Did it worsen with eye movement? Has the patient felt such pain before?

• Is the vision loss monocular or binocular? What was the patient doing or looking at when the vision loss was noted?

Optic neuritis tends to cause new eye pain over a week or so, generally with demonstrable vision loss in the affected eye. Recurrent pain with transient positive visual phenomena—have the patient alternately cover each eye to check—could be migraine, Dr. Costello says.

Also, females are more prone to optic neuritis and autoimmune disease. For NMOSD, the female to male ratio is almost 10:1.12

Beware the Mimics

Dr. Newman also discussed the following optic neuritis mimics:

• Macular causes of vision loss. These entities can imitate ON, and include such conditions as central serous retinopathy, which is more male prevalent. Other clinical differences: Central serous retinopathy doesn’t cause pain nor is there an afferent pupillary defect. An OCT scan will pick up subtle central serous retinopathy more acutely. Without an OCT, Dr. Newman says, “If you have someone with central vision loss, you might make a mistake, especially if they already have a diagnosis of MS, [because] fingolimod, for example, can affect central vision with macular edema.”

• Nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. NAION is unilateral, painless and causes sudden vision loss, due to a lack of blood flow to the front of the optic nerve. Disc swelling is always present, Dr. Newman says, adding that NAION is the most common misdiagnosis for ON.

• Compressive infiltrative optic neuropathy. Here, there could be sudden awareness of vision loss, like a person covers the affected eye and realizes he can’t see. If a compressive lesion is causing the vision loss, she says, an orbital MRI with contrast and fat saturation sequences will identify it.

• Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy. People with LHON have mitochondrial DNA point mutations. LHON is often mistaken as ON, says Dr. Newman, but LHON differs from optic neuritis as it is most often found in men, is painless and often presents as bilateral, or becomes so within months.

MRI scans with contrast, specifically of the patient’s orbits, are very helpful with diagnosis, she says. At least 90 percent of all acute cases of optic neuritis “will have enhancement of the optic nerve, but you won’t see that in Leber’s or with a maculopathy.”

• Lyme. Dr. Sergott adds that it can be prudent to also consider Lyme disease, because the optic nerve can have infectious inflammation.

Adverse events

Some drugs for certain diseases can affect the optic nerve, such as:

• Arrhythmia: Amiodarone or digoxin;

• Immune check point inhibitors;

• Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors;

• Cancer: Methotrexate, vincristine, and tamoxifen;

• Malaria: Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine;

• Infections: Ethambutol, chloramphenicol, isoniazid and sulfa-type antibiotics; and

• Others: Isotretinoin, linezolid, sildenafil, disulfiram.13

A word about misdiagnoses: The Stunkel paper found that 60 percent of the 122 patients referred to neuro-ophthalmology for possible ON were overdiagnosed. Migraine was misdiagnosed in 22 percent of these patients. “The most common diagnostic error, seen in 33 percent of cases, [was in] eliciting or interpreting the history”; the second, at 32 percent, was “not generating an appropriate differential diagnosis with alternative diagnoses.” 2

Treatments

Steroids have been the mainstay of treatment for ON for decades, and they primarily still are. “MOGAD responds briskly to steroids, and there’s a high risk of recurrence if steroids are taken away too fast,” says Dr. Bennett. Most cases of NMOSD don’t respond to steroids at all, adds Dr. Bennett, but have a more complete response to plasma exchanges, or PLEX.

IVIG, along with intravenous methylprednisolone, can be somewhat effective in preventing NMOSD relapses and extending the time period between attacks—as long as it’s given within days of onset.14

Three prescription medications are now approved for patients with AQP4 antibody-positive NMOSD, namely eculizumab, inebilizumab and satralizumab.

Referrals

As to referrals, Dr. Newman says, “You will only need to send those who make you uncomfortable or the diagnosis doesn’t seem right.”

Discerning what is going on with the optic nerve isn’t especially easy even with the tools in the ophthalmologist’s office, says Dr. Costello. Seeing inflammation behind the globe is tricky and in the areas around the retina and nerve itself, there’s less to see in cases of retrobulbar ON.

Diagnosis isn’t always apparent, even using those specialized tools in eye clinics, says Dr. Costello. It takes experience, she says, to appreciate an OCT’s pitfalls to properly interpret it. An experiment trying to connect ED physicians with more knowledgeable eye specialists—albeit for central retinal artery occlusion—for the purpose of remote consultations, cut treatment time down significantly. 15

Advances in artificial intelligence could aid with more rapid, accurate diagnoses. Using 1,599 fundus photographs, Dr. Costello and colleagues trained an AI algorithm to distinguish optic neuritis associated with MS from non-MS subtypes; the model was 76.2 percent accurate.16 While AI won’t replace a good history and examination to localize ON, she says tools like AI could help flag a patient who needs a quick evaluation for a non-MS optic neuritis subtype, like NMOSD.

Says Dr. Sergott: “Our job is to make as rapid a diagnosis as we can, to treat as quickly as possible.” Or forgo a definitive diagnosis, and just start treating, based on presentation, history and any other available information.

Dr. Bennett agrees. In lectures, he “points out certain features that would bias [the diagnosis] towards a rare disease.” In these situations, he advises “plasma exchange from the start.” As for risk vs benefit, he says overtreatment is preferable to the time lost “fiddling around to figure it out.”

Dr. Bennett reports fees from Alexion AstraZeneca Rare Disease, Antigenomycs, BeiGene, Chugai, Clene Nanomedicine, Genentech, Genzyme, Reistone Bio, Roche, Imcyse, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, and TG; speaker fees from Alexion; grants from Alexion and the NIH and the National MS Society. Dr. Bennett has a patent ‘Compositions and methods for the treatment of neuromyelitis optica.’ Dr. Costello has received speaker fees or advisory board honoraria from Alexion, Sanofi, Amgen and Novartis. Dr. Newman reports no relevant disclosures. Dr. Sergott consults for Amgen, Mallinckrodt, Roche and Novartis.

1. Hubbell AA. Optic neuritis and its significance as a symptom. Buffalo Med Surg J 1890;29:7:398-406.

2. Stunkel L, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Diagnostic error and neuro-ophthalmology. Curr Opin Neurol 2019;32:1:62-67.

3. Denis M et al. Optic nerve lesion length at the acute phase of optic neuritis is predictive of retinal neuronal loss. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2022;9:2:e1135.

4. Osborne B, Balcer LJ. Optic neuritis: Pathophysiology, clinical features, and diagnosis. UpToDate. Feb. 29, 2024.

5. Braithwaite T, Subramanian A, Petzold A, et al. Trends in optic neuritis incidence and prevalence in the UK and association with systemic and neurologic disease. JAMA Neurol 2020;77:12:1514-1523.

6. Stunkel L, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Diagnostic error and neuro-ophthalmology. Curr Opin Neurol 2019;32:1:62-67.

7. Pakravan P, Lai J, Cavuoto KM. Demographics, practice analysis, and geographic distribution of neuro-ophthalmologists in the United States in 2023. Ophthalmology 2024;131:3:333-340.

8. Beck RW, Gal RL. Treatment of acute optic neuritis: a summary of findings from the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:7:994-995.

9. Wang Y, Danzeng Q, Jiang W, et al. A retrospective study of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease from a clinical laboratory perspective. Front Neurol 2023;14:1187824.

10. Chen JJ, Tobin WO, Majed M, et al. Prevalence of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein and aquaporin-4-IgG in Patients in the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:4:419-422.

11. Bennett JL, Costello F, Chen JJ et al. Optic neuritis and autoimmune optic neuropathies: advances in diagnosis and treatment. Lancet Neurol 2023;22:1:89-100.

12. Levin MH, Bennett JL, Verkman AS. Optic neuritis in neuromyelitis optica. Prog Retin Eye Res 2013;36:159-71.

13. Prasad R, Singh A, Gupta N. Adverse drug reactions in tuberculosis and management. Indian J Tuberculosis 2019;66:4:520-532.

14. Lin J, Xue B, Zhu R, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin as the rescue treatment in NMOSD patients. Neurol Sci 2021;42:9:3857-3863.

15. Biousse V. An OCT-based remote diagnosis protocol may help emergency physicians identify CRAO. Ophthalmology. In press. https://www.aao.org/education/editors-choice/oct-based-remote-diagnosis-protocol-may-help-emerg.

16. Bénard-Séguin É, Nielsen C, Sarhan A, et al; COIL (Calgary Ophthalmology Innovation Laboratory). The role of artificial intelligence in predicting optic neuritis subtypes from ocular fundus photographs. J Neuroophthalmol. 2024 Aug 1 [Online ahead of print].