Tocilizumab and teprotumumab have been approved for treating giant cell arteritis and Graves’ disease, respectively. Here, we’ll take a look at what neuro-ophthalmologists have to say about these new treatments and how they can improve the standard of care for these diseases’ ocular complications.

Tocilizumab (Actemra)

Subcutaneous tocilizumab (Genentech/Roche) is now the only drug approved for treating giant cell arteritis in adults. GCA is an inflammatory disease of the small-to-medium-sized arteries that usually manifests with headaches, weight loss, scalp tenderness or jaw claudication. It’s more prevalent in women than in men, and the likelihood of developing the disease increases with age. “Someone who is 80 years old is more likely to get it than someone who’s 60,” says August L. Reader III, MD, FACS, a neuro-ophthalmologist in practice at Pacific Eye Associates in San Francisco. “Patients can have strokes, heart attacks, abdominal infarctions—anything that has an artery in it can become inflamed, decreasing circulation to that tissue.”

This humanized monoclonal antibody was first approved in 2010 for treating rheumatoid arthritis, and approved a year later for treating systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. “It has a long history of treating these diseases, and that gave people confidence that it could be used in GCA as well because we already knew what the side effects were,” says Dr. Reader. “The preliminary trial took place in Switzerland on five patients with GCA who were on prednisone. With tocilizumab, they were able to get them off the steroid quicker.”

Tocilizumab works against the interleukin-6 receptor, a main inflammatory cytokine that modulates the body-wide immune response. But as with any drug that represses the immune system, Dr. Reader says clinicians should be mindful of current and past patient medical history. “You should not prescribe this drug if the patient has an active infection, a compromised immune system, a history of tuberculosis or hepatitis B, or if they live in an area with a high prevalence of fungal infections, such as the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and the Southwest,” he says.

Tocilizumab has no ocular side effects, but Dr. Reader says you should monitor your patient’s blood work carefully. “Patients can get neutropenia or thrombocytopenia from this medication,” he says. “They may also have increased liver function enzymes that will increase their lipid profile, so be sure to watch for elevated cholesterol and triglyceride levels.”

|

Ocular Manifestations of GCA

In the eye, the biggest problem caused by GCA is an acute ischemic optic neuropathy. Patients can go blind from this disease complication, and until the introduction of tocilizumab, glucocorticoids were the only treatment.

“When you have someone with an acute ischemic optic neuropathy, elevated sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein and the classic symptoms, we put them on high-dose steroids immediately to protect the other eye,” Dr. Reader says. “The original studies decades ago showed that if you put the patient on steroids immediately, there’s a good chance you can protect the other eye from getting it; however, if they get it in one eye and don’t go on steroids, there’s a greater-than-50-percent chance that it’ll go to the other eye in three weeks. That’s why getting the patient on steroids is so essential: to protect second-eye vision.”

Dr. Reader says he checks for elevated sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein when patients are referred to him with headaches. If they’re also presenting with the classic symptoms, he begins steroid treatment immediately. Typical steroid dosing for GCA is 60 to 80 mg per day. “We monitor patients closely based on sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, and as they get better, we reduce the steroids based on the blood-work numbers. In most cases, before tocilizumab, patients would remain on steroids for about two years, slowly tapering. Studies show that giant cell arteritis sort of burns itself out after about two years, so if you get them on steroids, your biggest problem is mainly the steroid side effects. That’s why tocilizumab is a real breakthrough for this disease.”

Tocilizumab Studies

“Two studies showed that tocilizumab therapy significantly increased the number of GCA patients that remain in remission after tapering off corticosteroid therapy, compared with placebo-treated patients,” says Kenneth S. Shindler, MD, PhD, a professor in the departments of ophthalmology and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania’s Scheie Eye Institute in Philadelphia.

In the first study in The Lancet in 2016,1 20 patients received tocilizumab subcutaneously and 10 patients received the placebo. Both groups were given oral prednisolone. “This study showed that at the end of the full dosing period (24 weeks), there was an 85-percent response rate, and they were able to get patients off steroids in about 12 weeks,” says Dr. Reader. “Only 40 percent of the placebo group achieved remission. At one year, 85 percent of the treated group was still relapse-free, whereas only 20 percent of the placebo group was relapse-free.”

The researchers found that the mean survival-time difference to stopping steroids was 12 weeks in favor of tocilizumab, which they noted led to a cumulative prednisolone dose of 43 mg/kg in the tocilizumab group versus 110 mg/kg in the placebo group after one year. Half of the placebo group patients experienced serious adverse events, compared to seven patients (35 percent) in the treated group.

The major FDA trial for the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous tocilizumab included 251 patients with GCA, divided into four groups to receive subcutaneous tocilizumab (at a dose of 162 mg/kg) weekly or every other week combined with a 26-week prednisone taper, or placebo with a prednisone taper over a 26- or 52-week period.2 Here are some of the findings:

• At week 52, 56 percent of patients treated with tocilizumab weekly and 53 percent on the every-other-week dose achieved sustained remission.

• At week 52, 14 percent of the placebo group on the 26-week prednisone taper and 18 percent on the 52-week taper achieved sustained remission. These differences between the tocilizumab and placebo groups were significant (p<0.001).

• Cumulative mean prednisone dose over one year was 1,862 mg in the tocilizumab groups, 3,296 mg in the placebo group on the 26-week taper and 3,818 mg for the 52-week taper (p<0.001).

• Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy developed in one patient in the tocilizumab every-other-week group.

Both studies support the use of tocilizumab for GCA, but Dr. Shindler notes that the continued need for a fairly long course of corticosteroids is still a limitation. “From the perspective of an ophthalmologist,” he adds, “the studies weren’t designed to examine effects in those patients that specifically present with ocular manifestations of GCA. Those patients may have unique disease susceptibility that may or may not respond to tocilizumab as well as patients without ocular manifestations of their GCA.”

Dr. Shindler says that it would be good to know if tocilizumab is effective in suppressing GCA without the need for concurrent steroid treatment, but he adds, “I suspect this would be difficult to study, given the long history and successful use of steroids.”

Dr. Reader says studying the use of tocilizumab alone as an initial treatment for GCA will also likely be difficult because the chance of vision loss from acute ischemic optic neuropathy is too great a risk.

Dosing for GCA

Injections are typically done by a rheumatologist. The recommended dosing for GCA is one prefilled syringe of tocilizumab (162 mg) once a week, in combination with a tapering steroid treatment. Dr. Reader notes that for patients under 100 kg of weight, every-other-week dosing is preferred. “There’s an initial loading dose, and then it’s double the dose every three weeks thereafter for a total of eight infusions, either IV or subcutaneous injection,” he says.

“Just as with any medication that reduces the immune response, be wary of secondary infections,” Dr. Reader continues. “Most of these patients are already on steroids before they start tocilizumab, which would reduce their resistance even further. Preventing and watching out for new infections or exacerbations of infections is key. Tocilizumab decreases the white blood cell count and platelet count in the body.”

Teprotumumab (Tepezza)

Teprotumumab-trbw (Horizon) was approved on January 21 for treating active Graves’ disease in adults, based on two multinational clinical trials. “This drug was developed specifically for Graves’ disease and it’s the first drug approved for it,” Dr. Reader says. “Everything we’ve used in the past has been off-label, like corticosteroids, azathioprine and methotrexate—mainly cancer drugs with variable responses. That’s why it’s exciting to have something specifically for Graves’ disease. Teprotumumab will make a huge difference in lessening the treatment burden.”

Teprotumumab blocks insulin-like growth factor-1, which is elevated in those with Graves’. As a thyroid hormone disease, Graves’ disease is usually treated by an endocrinologist.

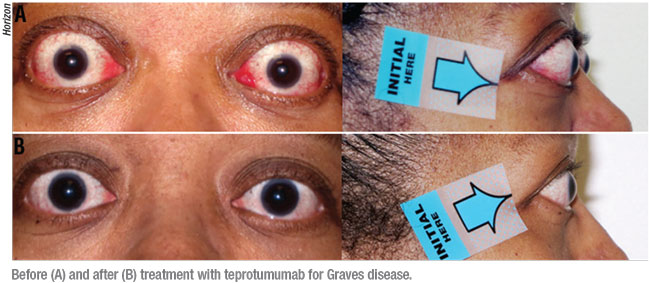

“In Graves’ disease patients, the muscles and fat around the eye become inflamed and cause proptosis,” Dr. Reader says. “This leads to different side effects of exposure such as dry eye and double vision because of the muscle enlargements.”

He says that Graves’ disease-related eye problems have always been challenging to treat. Steroids have been the go-to therapy, as well as radiation and surgery. “Studies out of the Mayo Clinic demonstrated that if someone is steroid-sensitive, has Graves’ disease and is beginning to experience severe side effects from steroids, orbital radiation to kill the inflammatory cells and decrease the muscle size is effective,” he says.

“Usually the patients who receive radiation are the ones with double vision,” he continues. “We also see a reduction in diplopia [with radiation]. A patient may come in with 20 D of hyperopia and 15 D of esotropia or exotropia and the steroids just don’t clear it up. We do the radiation, specifically to the affected muscles causing the diplopia, and in most cases, we’re able to get the eyes back together close enough to allow us to control the disease with a little bit of surgery, or in some cases, just prism and glasses.”

Dr. Reader reminds us that, so far, no treatment has been perfectly successful, but in severe cases, invasive surgery has helped. “In extreme cases where the proptosis is so bad that it’s constricting the optic nerve and the patient is starting to lose vision, we do an orbital decompression,” he says. “This involves going in surgically and removing the two lateral walls and roof of the orbit—removing the muscles—so this enlarged tissue mass can expand into those areas and give relief to the optic nerve. But that’s rarely done today and only in extreme cases. I think I’ve had only three cases in the past 10 years that required surgery.”

Safety and Efficacy

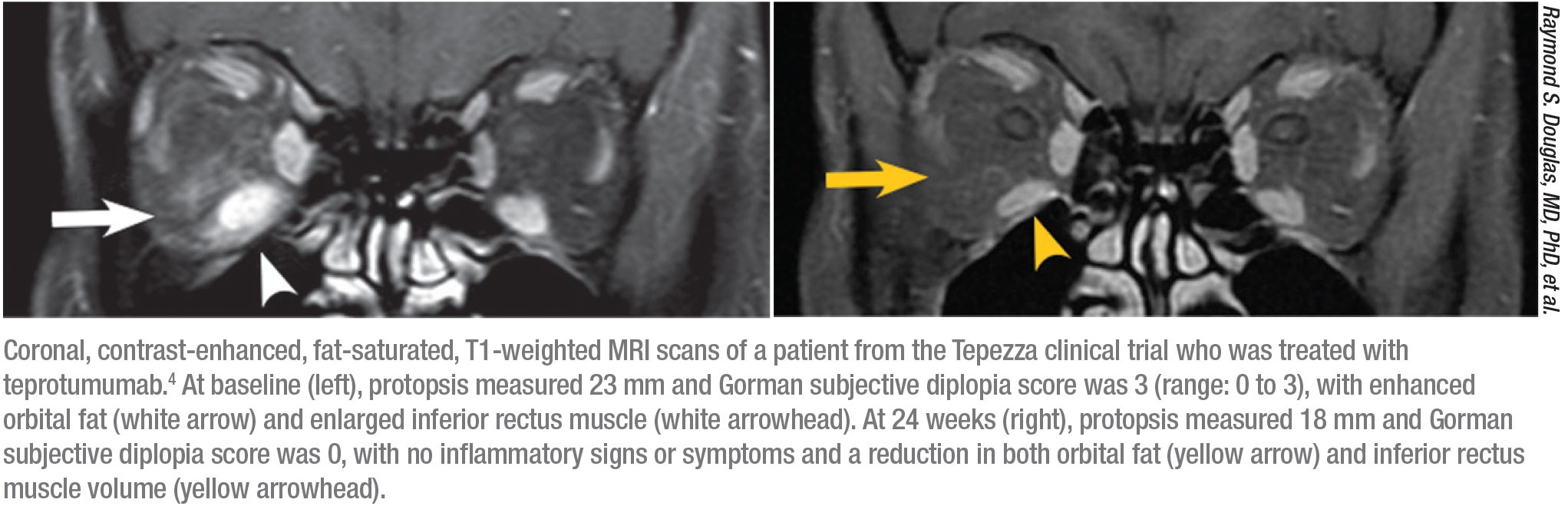

The original safety study for teprotumumab, done in two arms, included 170 patients—84 received the drug and 86 received a placebo.3,4 “In the first arm, proptosis improved by 2.5 mm in the treated group but only 0.2 mm in the placebo group,” Dr. Reader says. “The response was 69 percent in the treated group and 20 percent in the placebo group at 24 weeks (p<0.001).” The only drug-related adverse event in the first arm was hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes, which was controlled by adjusting their diabetes medication.

“In the follow-up study (41 treated, 42 placebo), the response rate was 83 percent among treated patients and 10 percent among the placebo group,” he continues.4 “The reduction in proptosis was 2.8 mm in the treated group and 0.5 mm in the placebo group. Of all the patients in the beginning of the study, 73 percent had diplopia, and at the end of the 24-week study, diplopia was gone in 54 percent of the treated group and in 25 percent of the placebo group.”

“These two clinical trials demonstrated significantly better improvement in multiple features of thyroid-related orbitopathy, including proptosis and clinical activity scores in patients treated with teprotumumab compared to patients treated with placebo,” Dr. Shindler says. “Additionally, the studies were well-designed and the benefits were convincing without significant or serious adverse effects. One potential limitation is that the results weren’t directly compared with pulsed intravenous steroids, which are often used for active thyroid orbitopathy.”

Teprotumumab is relatively safe, as far as side effects are concerned, but the drug may cause hyperglycemia and exacerbate existing irritable bowel disease. “If someone is diabetic or glucose intolerant, teprotumumab may worsen or kick them over into diabetes,” Dr. Reader explains. “That’s occurred in about 10 percent of patients in studies. Then with IBD, where patients already have reduced IGF-1, adding anything that will further reduce IGF-1 will make the disease worse.”

Per the final FDA approval, teprotumumab is administered intravenously. “Patients start off with an initial dose of 10 mg/kg and then three weeks later they’re given 20 mg/kg,” Dr. Reader explains. “They do the 20 mg/kg for six more sessions, for a total of one 10-mg/kg and seven 20-mg/kg infusions. The infusion goes in over about an hour and a half, but those who tolerate it well may take it over one hour.”

|

Lessening Treatment Burden

Both tocilizumab and teprotumumab stand to lessen the treatment burden for their respective diseases, which, as Dr. Shindler notes, are currently treated—with varying success—with corticosteroids, which themselves carry the potential for significant adverse effects.

“The data for each therapy is compelling,” he says. “They suggest that these drugs should become important options for standard-of-care therapy in appropriate patient populations—e.g., GCA patients that can’t wean off of corticosteroids without signs of relapsing and thyroid orbitopathy patients with active, progressive disease.

|

“The studies suggest roles for both therapies as first-line agents,” he continues, “although I suspect they likely will be used more as second-line agents for a while, given a number of factors, including cost of therapy and current practice patterns using corticosteroids that may be difficult to convince practitioners to replace. For teprotumumab, one barrier is the complex nature of the thyroid orbitopathy disease that has made it difficult to quantify features that define the disease state in each patient.”

Another barrier is cost. Dr. Reader says that, without insurance, cost may be a major obstacle for accessing these drugs; it runs in the thousands of dollars, unlike corticosteroids. “Monoclonal antibodies are expensive to develop,” he says, “and since these diseases affect only a small percentage of the population, their use will be niche and it may take several years before the cost begins to come down.” REVIEW

Dr. Reader and Dr. Shindler have no related financial disclosures.

1. Villiger PM, Adler S, Kuchen S, et al. Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: A phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:10031:1921-7.

2. Stone JH, Tuckwell K, Dimonaco S, et al. Trial of tocilizumab in giant-cell arteritis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:317-28.

3. Smith TJ, Kahaly GJ, Ezra DG, et al. Teprotumumab for thyroid-associated ophthalmopathy. N Engl J Med 2017;376:18:1748-61.

4. Douglas RS, Kahaly GJ, Patel A, et al. Teprotumumab for the treatment of active thyroid eye disease. N Engl J Med 2020;382:4:341-52.