Many trabeculectomies fail over time, even if the surgery itself goes perfectly. That’s true for a number of reasons, including that patients heal differently; they may or may not use their postop drops or follow up as instructed; or they may have a preexisting condition that influences the final result. (Ideally, you’ve taken these factors into account when choosing your procedure.)

|

When a trabeculectomy does be-gin to fail, it’s usually the result of scarring. Because scarring is a gradual process, a sudden trabeculectomy failure is unusual; it’s more common to have trabeculectomy function decrease slowly over time. How long a trabeculectomy remains viable varies widely; some trabeculectomies don’t fail during the patient’s lifetime. A few of my patients have had a working trabeculectomy for more than 20 years—although those patients are in the minority.

The reality is that most patients who need a trabeculectomy are elderly. The prevalence of glaucoma increases in older patients, especially among those older than 80. For that reason, a trabeculectomy that works well for five to 15 years may be sufficient to prevent significant vision loss in these patients for the rest of their lives. Younger patients tend to heal better than older patients, increasing the likelihood of trabeculectomy failure, which may necessitate consideration of treatment options other than trabeculectomy for those patients.

Of course, failing to lower pressure enough isn’t the only thing that can go wrong with a trabeculectomy. Trabeculectomy blebs can leak, which is dangerous because of the risk of infection. A leak can also cause hypotony maculopathy and blurred vision. Furthermore, blebs can some-times expand across the globe in ways that irritate the patient’s eye or cause a cosmetic problem. To put this another way, some trabeculectomy problems make the doctor unhappy; other problems make the patient unhappy.

Here, I’d like to discuss some common problems that can arise following a trabeculectomy and the options for addressing them. First, I’ll discuss the issues that are disappointing to the doctor; then I’ll talk about issues that bother the patient.

When a Bleb Scars Down

When a bleb has become less effective, that usually means that the conjunctiva and supporting tissues have scarred down to the sclera. This occurs in one of two ways: either as generalized scarring that leaves the bleb looking fairly flat, or presenting as a dome-like bulge, often referred to as an encapsulated bleb or “Tenon’s cyst.” Either type of scarring results in poor pressure control. A large, diffuse bleb without significant scarring is much more likely to successfully lower IOP.

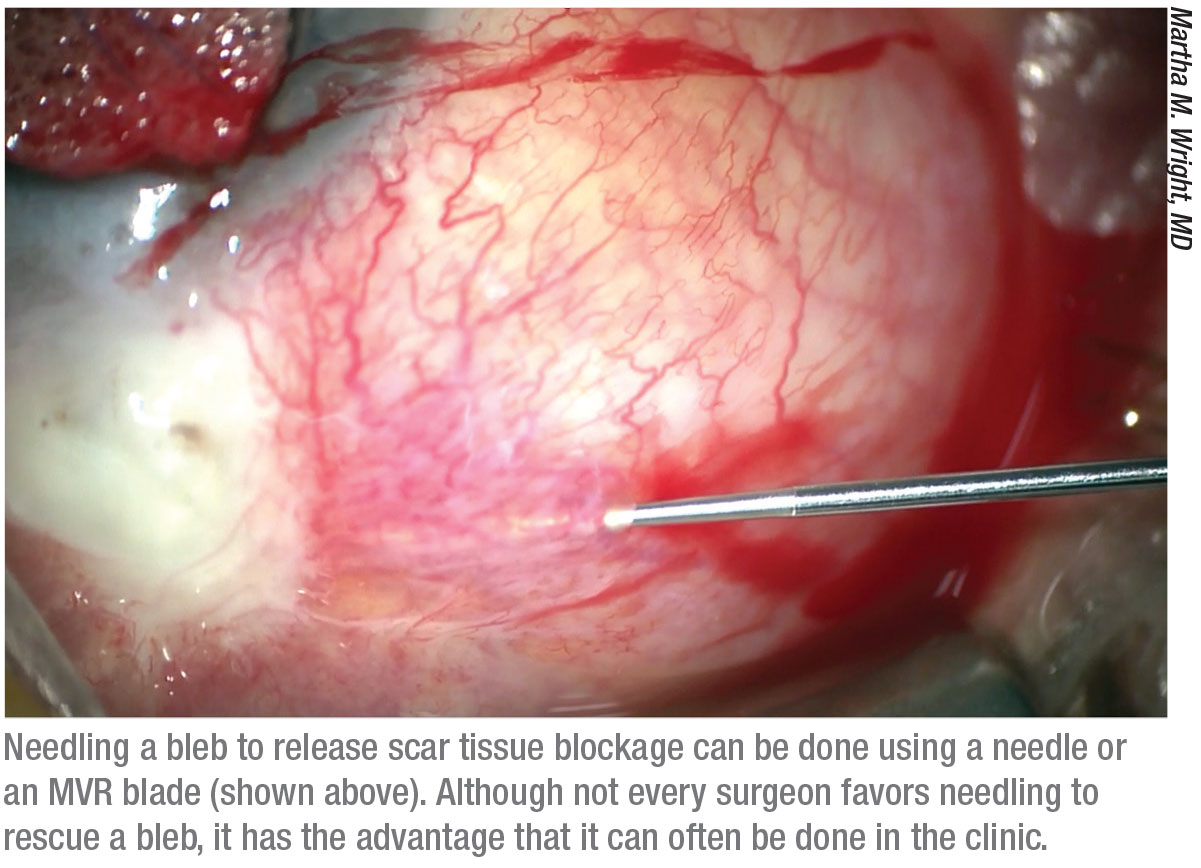

Generally, when a bleb has become less functional because of scarring, we have several options: Add topical medications; perform a different glaucoma procedure; try to release some of the adhesions using needling; or perform a surgical revision. There are several ways to needle or revise a bleb—which means there are problems with every method and no one “best” way. Prevailing opinions about the efficacy of needling seem to differ from practice to practice. Some doctors do a lot of needling to try to restore bleb functionality if the scarring isn’t too serious, while others do almost none.

Needling has one big advantage over surgical revision: In some cases it can be done in the clinic. Whether or not you choose to needle a bleb in the clinic is partly a matter of personal preference and partly an issue of patient cooperation. If needling is going to be relatively quick and the patient is very cooperative, you may be able to do it at the slit lamp. If it’s more involved, or you have concerns about how well the patient will be able to hold still, you may choose to do it in the OR. However, once you plan to perform needling or a surgical revision in the OR, it’s worth considering whether this is the best use of resources. It might make more sense, in selected cases, to do a completely different procedure such as a tube shunt surgery that could have a higher rate of success.

|

Needling is usually done with one of two tools: a bent needle or a blade such as the MVR. Bending the needle to a 45-degree angle makes it possible to ergonomically reach over an obstacle such as the patient’s brow. (Of course, if you’re coming in from the temporal side, it’s fine to leave the needle unbent.) The needle bevel allows you to use it like a blade. However, the sharp area of the tip is small and the shaft of the needle is flexible, making it hard to cut through thick scar tissue effectively. For that reason, when the needle is used, the surgeon often pokes a series of perforations through the scar tissue and then moves the needle side-to-side to “connect the dots.” The resistance to cutting through the scar tissue may cause the eye to move around a fair amount when breaking through the scar tissue.

Unlike a needle, the MVR blade has a longer sharp edge and is more rigid, making it easier to cut or saw through scar tissue. (You can watch a video of this technique at the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s website: aao.org/basic-skills/bleb-needling-failed.) I don’t bend the MVR blade, so I tend to use it in the OR where I have more control over the position of the eye.

Generally, needling is directed at the area you believe is restricting the flow of aqueous. The needle may be directed subconjunctivally, beneath the scleral flap, or through the sclerostomy. Some surgeons have even developed an ab interno approach for needling, in which a 23-gauge needle enters the anterior chamber across from the trabeculectomy, is passed across the anterior chamber and out the sclerostomy, with the tip of the needle at the posterior lip of the scleral flap.1

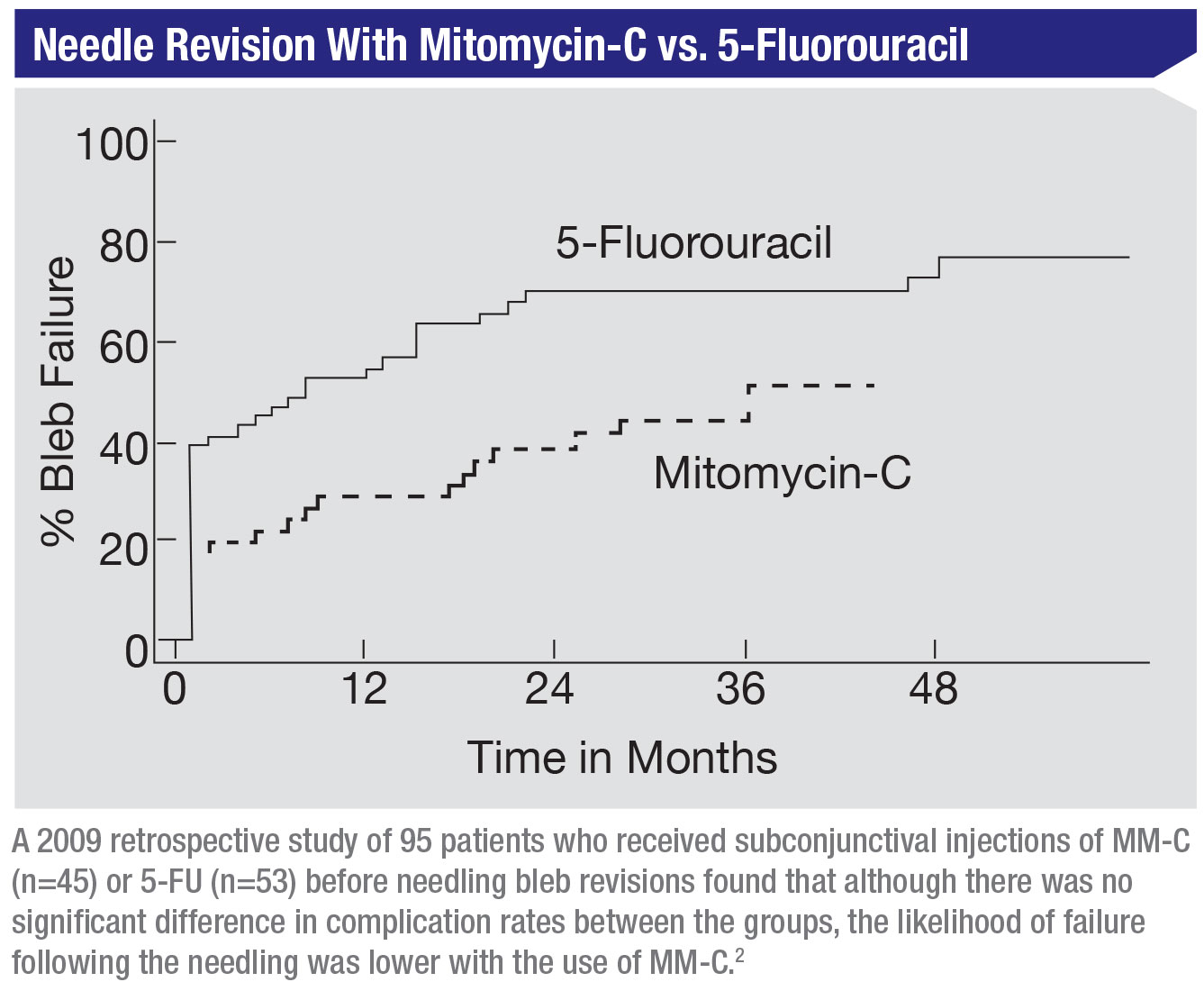

If the needling procedure isn’t done in the first week or two after surgery, it may be worthwhile to add an antifibrotic, either mitomycin-C or 5-FU, to help ensure that the scarring doesn’t immediately resume. (In a published study comparing these two drugs as an adjunct to needling, mitomycin-C was shown to be to be more effective than 5-FU.2)

Another option for a failing bleb is surgical revision.3 This entails going back to the OR, applying mitomycin-C and revising the trabeculectomy to reestablish the flow. This usually means dissecting the conjunctiva again and cutting through some of the scar tissue that’s impeding the flow of aqueous. The surgeon may or may not dissect the flap completely free. Unlike needling, where one does not have to close up or suture the entry site if it’s some distance from the scleral flap, a surgical revision requires creating an incision, so you have to close it when you’re finished.

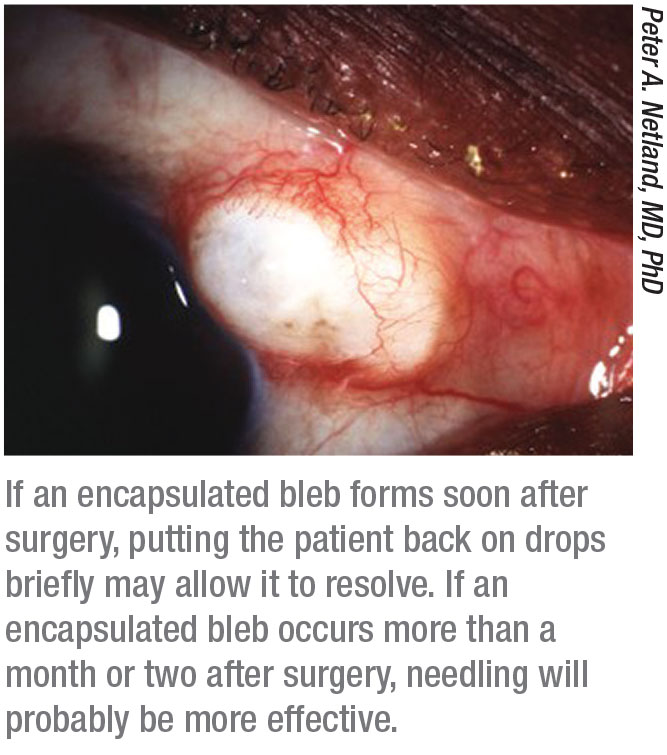

Managing Encapsulated Blebs

Some patients develop an en-capsulated bleb early on following surgery. Unfortunately, studies have shown that pressure control isn’t as good in trabeculectomy patients who have—or have had—an encapsulated bleb.

If an encapsulated bleb develops soon after surgery, it may resolve on its own, but many encapsulated blebs do not. Generally, when we do a trabeculectomy we don’t want to put the patient on any glaucoma medications in the early postoperative period because the flow of fluid through the trabeculectomy site is essential to the functioning of the trabeculectomy. Suture lysis to increase flow and lower the pressure is usually preferred over adding medication after surgery, often in conjunction with digital massage. The one exception to this rule is when there’s early encapsulation of the bleb. Laser suture lysis and digital massage may not be possible or effective in this scenario.

|

While some have recommended needling for early bleb encapsulations, studies have shown that in the first few weeks after surgery putting the patient back on drops may be more effective than needling. In many cases this will result in the bleb reverting to a more normal-looking trabeculectomy bleb. However, once you get more than a month or two from surgery, needling will probably be more effective than putting the patient back on drops. (Absent encapsulation, the strategy of needling to release scarred tissue is more effective when done soon after the surgery than when it’s done years later, because the scar tissue will have become very well established at that point.)

Managing a Bleb Leak

Bleb leaks are often associated with very thin bleb tissue, typically found in blebs that have a lot of scarring around them. The scarring makes the bleb smaller, and as blebs get smaller and more compressed the tissue tends to get thinner. This phenomenon has been likened to putting air into a balloon or surgical glove and then squeezing the air down into one tiny area; the balloon wall gets thinner and thinner. If a leak develops, the longer it leaks, the harder it is to close it up. As with trabeculectomies themselves, the flow of fluid keeps the hole open.

Bleb leaks are fairly common. That’s especially true when an antifibrotic was used during the trabeculectomy, because the antifibrotic causes the bleb to have a thinner wall. Trabeculectomies performed with an anti-fibrotic also tend to continue to function longer, allowing more time for a leak to occur. It’s possible that some leaks are intermittent, and therefore may be missed by the surgeon, but a persistent leak can lead to a bleb infection—or worse, endophthalmitis. So, when we dis-cover a persistent leak, it’s usually a good idea to try to repair it.

A persistent leak may be discovered in any of several ways. The patient may report a sudden increase in what they believe is tearing. They may wake up with a wet pillow, or report blurred or fluctuating vision. The surgeon may note that the patient’s intraocular pressure is suddenly lower, or note a suspiciously thin area or a frank hole in the conjunctiva. Confirmation of a leak is done with Seidel testing.

There are many methods for trying to fix bleb leaks, but none of them is perfect. They include lowering the pressure by putting the patient on medication; patching the eye; or putting the patient on an eye drop that’s a little irritating to encourage healing. Some clinicians may perform autologous blood injections into the bleb, and/or as a peri-bleb injection, which can be helpful in some cases. But in many cases you have to go back to the OR and do something surgically. The main thing is to not create a bigger problem than the one you’re trying to fix.

Some of the most common surgical approaches involve pulling in healthier conjunctiva from the surrounding area to cover the leak, with or without removing the leaking tissue. Unfortunately, some eyes are so scarred that you can’t move the surrounding conjunctiva—it’s like concrete. In some patients, autologous conjunctival patch grafts can be considered. Some surgeons have tried repairing a bleb leak by simply securing a piece of amniotic membrane on top of it, thinking that if the tissue remained there for a while it would heal the leak. Unfortunately, in practice that doesn’t work very well.

My preference is to place an amniotic membrane under the conjunctiva. Rather than bringing healthier conjunctiva in, I lift up the patient’s leaking conjunctiva, secure the amniotic membrane over the trabeculectomy site, put the conjunctiva back on top of the membrane and close the incision. The amniotic membrane tissue is a bit tedious to work with; it’s kind of like manipulating a wet Kleenex. However, all procedures for fixing bleb leaks can be difficult, and I’ve had good success with this approach. I believe the amniotic membrane acts as a scaffold; the conjunctiva grows over it during the next week or so, healing the leak.

When the Patient is Unhappy

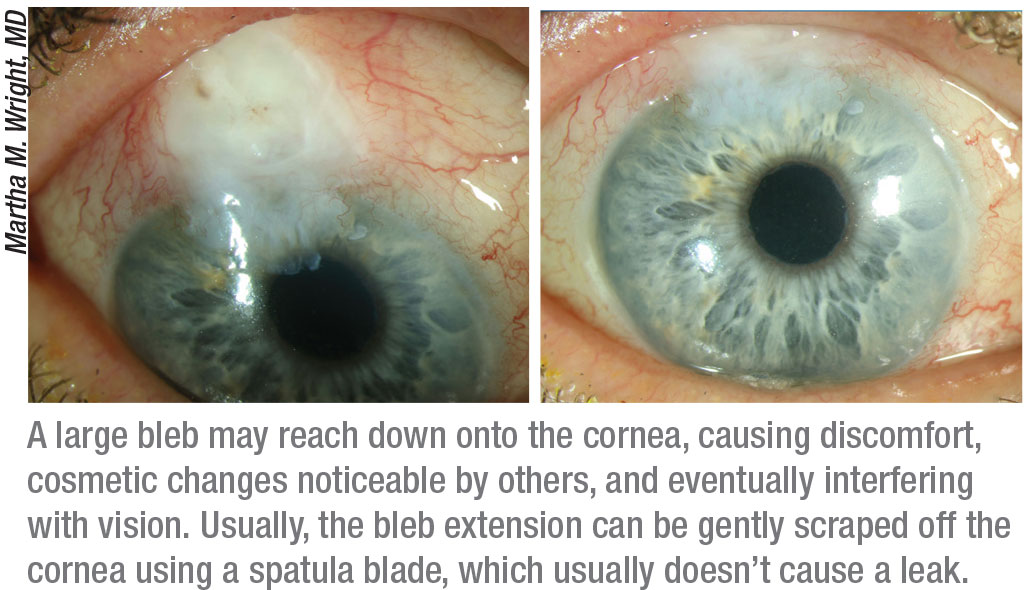

Occasionally, even after excellent pressure is achieved, changes in the bleb can make the patient unhappy. Most often this is because the bleb has expanded in size. A large bleb can be uncomfortable and/or produce unwanted cosmetic changes.

Sometimes a bleb extends down onto the cornea, slowly expanding toward the visual axis. In addition to making the patient uncomfortable, this can interfere with vision. The bleb is white and translucent (see examples, below) and tends to produce some scar tissue, so you don’t want it to get into the visual axis. It can also alter the appearance of the eye, causing people to ask the patient: “What’s wrong with your eye?”

|

The good news is that you can gently scrape the bleb extension off the cornea using a spatula blade and amputate it at the limbus. The bleb on the cornea usually peels up back to the limbus once you get it started. Surprisingly, this generally doesn’t cause the bleb to leak; you usually don’t have to do any suturing. In most cases, the cornea will re-epithelialize and the bleb won’t start working its way back onto the cornea again—although sometimes it does, possibly requiring another excision.

If a bleb gets very large, it can cause bleb dysesthesia, making the eye uncomfortable—usually because it’s interfering with the tear film. If the bleb protrudes, it can prevent the eyelid from moving over the eye in a smooth motion, and patients can feel it when they blink. Furthermore, a large bleb at the limbus can prevent the blinking reflex from spreading the tear film evenly over the cornea. This can create a dry spot, or dellen, resulting in a constant foreign body sensation that can be very uncomfortable. Some enlarged blebs cause a bubble to form on the edge of the lid, and the bubble pops every time the patient blinks. The patient can either feel the pop or hear it—or both! That’s distracting, given the number of times a day we blink.

|

Occasionally, a bleb may simply expand all the way around the limbus, creating a bleb 360 degrees around the eye. Ironically, the IOP is usually excellent when this happens because a lot of aqueous is exiting the eye. Unfortunately, the large bleb may be uncomfortable and patients can be very unhappy if they feel the bleb every time they blink.

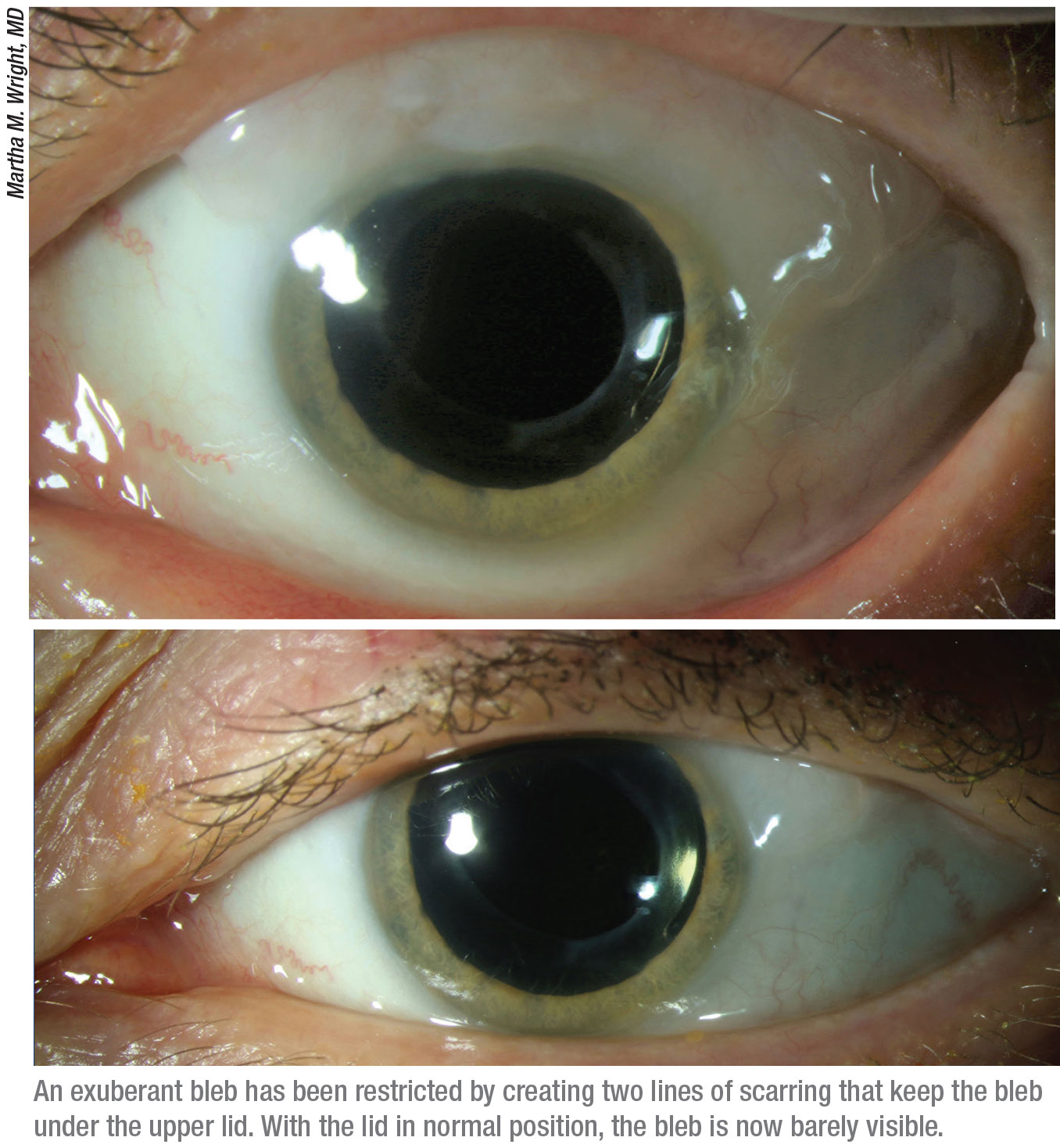

Often, these “exuberant blebs” will flatten out on their own given time—but not always. If it remains, you need to do something to make the patient more comfortable by limiting the extent of the bleb. In some instances, a laser re-shaping procedure (using a surgical marking pen as a chromophore for laser absorption) can lower the profile of the bleb, or reshape it. Some authors have recommended putting tight sutures over the lines you want to scar down; this would create enough scarring that the bleb should stay up under the eyelid and away from the palpebral fissure where it’s most likely to be felt by the patient. You can reliably create two lines of scarring that will contain the bleb in a more limited area by making incisions through the conjunctiva down to bare sclera. (See images.)

I’ve done this procedure in the clinic at the slit lamp and in our treatment room, using a topical anesthetic, although you certainly could do it in the OR. Most patients who were miserable before this procedure have been very happy after a few days of healing.

Doing What Works

As we all know, trabeculectomy is not a perfect procedure, but it remains an important part of our treatment armamentarium. When we feel that a patient needs a trabeculectomy to prevent a loss of vision, strategies like those described here can help to restore a less than perfect bleb, allowing our patients to benefit from the lower pressure it provides. REVIEW

Dr. Wright is a professor in the department of ophthalmology and visual neurosciences at the University of Minnesota, and a glaucoma specialist at the Veterans Affairs Hospital in Minneapolis. She reports no financial ties to any product mentioned in this article.

1. Lee GA, M Desiree, Shah P. Ab interno bleb needling revision: A new approach. Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology, 2016;45:4:409-410.

2. Anand N, Khan A. Long-term outcomes of needle revision of trabeculectomy blebs with mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil: A comparative safety and efficacy report. J Glaucoma 2009;18:7:513-520.

3. Chen PP, Moeller KL. Smaller-incision revision of trabeculectomy with mitomycin: Long-term outcomes and complications. J Glaucoma 2019;28:1:27-31.