Another consistent cause of explantation still evident in this year’s survey is incorrect lens power. “Overall, it’s still the third most common reason for explantation,” Dr. Mamalis says. “This may partly reflect the fact that we’re now dealing with a large group of patients who’ve had refractive surgery.”

Dr. Mamalis notes that some lenses appear to have a propensity for calcification. “Some silicone lenses—both one-piece plate lenses and three-piece lenses—are being explanted because of calcification on the posterior surface in the setting of asteroid hyalosis, especially when the patient has had a YAG capsulotomy,” he says. “This is something we’ve just been seeing recently. Also, the hydrogels—the hydrophilic acrylics—have more of a propensity to calcify than the other materials, and they are most often being removed for this reason. The latter are still very commonly used outside the U.S., but the number used in the United States is quite small.”

Perhaps not surprisingly, multifocal implants are being taken out for different reasons. “Multifocals are often removed because of dysphotopsias—glare, haloes and things like that—while we’re seeing far fewer reports of explantation due to dislocations and decentrations,” says Dr. Mamalis. “It may be that if you’re putting in a multifocal you have to make sure you have a perfect capsulorhexis, an absolutely intact capsule and no chance of that lens not being perfectly centered. Surgeons tend to only implant multifocals in situations where the cases are likely to go perfectly.”

Dr. Mamalis notes that the survey has several limitations. “Initially, the survey was seven pages long, which provided a lot of detailed information,” he says. “However, in the interest of getting a greater number of responses, we shortened it. As a result, we now end up with data that’s not broad enough to answer some of the questions people would like to ask. In addition, we don’t know the actual number of explantations of each lens that are taking place. We can only say that if you use this type of implant, these are the complications that are associated with the need to explant or exchange it.

“To avoid having to explant lenses, we have to have excellent surgical technique, and the implant has to be completely inside the capsular bag, to decrease dislocation,” Dr. Mamalis concludes. “We have to have accurate IOL measurements so we can minimize incorrect lens power. And of course, proper patient selection for multifocal lenses is critical.”

Dr. Mamalis adds that this is an ongoing survey. “If you have explanted IOLs and you want to report them, the survey is available on the ASCRS and ESCRS websites,” he says. “Please fill it out so we can keep this going for many years to come.”

Fovista Enhances Lucentis Wet AMD Treatment

The ongoing study of angiogenesis in ophthalmology suggests that the addition of platelet-derived growth factor antagonists (anti-PDGFs) to anti-VEGF treatment can improve outcomes.

Ophthotech (New York, N.Y.) recently announced the results of its global, multicenter, randomized and double-masked Phase IIb trial of Fovista (pegpleranib) injected in combination with Lucentis. The study is published online in Ophthalmology at: http://www.aaojournal.org/inpress. It demonstrates that Fovista, administered monthly at a 1.5-mg dose in combination with 0.5 mg of Lucentis for a period of 24 weeks, was more effective than Lucentis alone in improving acuity in patients with wet AMD.

The combination-therapy group receiving 1.5 mg of Fovista with 0.5 mg of Lucentis achieved the greater gain in visual acuity: 10.6 EDTR letters at week 24, representing a 62-percent relative improvement from baseline. The Lucentis monotherapy group gained 6.5 letters at week 24.

Vascular endothelial growth factor antagonists intercept VEGF, a chemical that triggers choroidal neovascularization in wet AMD. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), however, signals pericytes to form a protective sheath around the diseased blood vessels as they grow. As a result, once a choroidal neovascular membrane is mature, however, the ability of anti-VEGF alone to slow or stop its growth is limited. Adding an anti-PDGF to anti-VEGF treatment is thought to help the anti-VEGF work better by disrupting PDGF signaling and stripping out the pericytes, leaving the CNV membrane vulnerable to the effects of anti-VEGF therapy.

Study author Glenn J. Jaffe, MD, Robert Machemer Professor of Ophthalmology at Duke University, says, “Combination therapy, when compared to anti-VEGF monotherapy, also resulted in less fibrosis and better resolution of subretinal hyper-reflective material,” which is associated with poorer visual acuity. “The results support the hypothesis that the two drugs work by complementary mechanisms,” Dr. Jaffe adds.

“For the past 10 years or so, we’ve been really fortunate to have a great treatment in Lucentis for patients with wet AMD,” says Sunir J. Garg, MD, ophthalmologist at the Wills Eye Hospital’s retinal service and associate professor of ophthalmology at Thomas Jefferson University. “Since then, however, we haven’t had another revolutionary treatment. Some patients still don’t respond well to our current anti-VEGF treatments. Perhaps Fovista will enable some of those patients who don’t respond well to current therapies to get better acuity improvement.”

Ophthotech says that results of two Phase III clinical trials of Fovista plus Lucentis will be forthcoming.

Dr. Garg reports that he was a subinvestigator for the Fovista trials, and is a member of the speakers’ bureau for Roche-Genentech.

Chlorhexidine and Colistin Resistance

In a study published online ahead of print in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, researchers in England found a pathogen that is now resistant to chlorhexidine, a bisbiguanide antiseptic that’s widely used as a handwash and disinfectant in health-care settings.1 Perhaps more alarming for surgeons, however, is that researchers found that this resistance to chlorhexidine resulted in a cross-resistance to the antibiotic colistin.

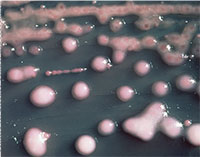

While antiseptic resistance has been reported before, there’s a lack of understanding of the mechanisms that allow it to occur. In this study, researchers tested different strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the hopes of better understanding the adaptation to chlorhexidine and the development of the antibiotic cross-resistance. In five of six strains of K. pneumoniae, adaptation to chlorhexidine also led to a resistance to the antibiotic colistin. Researchers say that this risk of resistance to colistin emerging in K. pneumoniae may have implications for infection-prevention procedures.

|

| K. pneumoniae has developed resistance to an antiseptic and a powerful antibiotic. |

Randall J. Olson, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at the University of Utah School of Medicine, says the finding exerts more pressure on physicians to find new ways to fight infection. “This finding is so new we will have to look at other non-antibiotic disinfectives,” he says. “However, it may not be as simple as switching antiseptics, as these too may result in cross-resistances.”

The implications of this study are important for the treatment of multi-drug resistant K. pneumoniae infections and outbreaks, as many resistant strains are susceptible to only a few antibiotics, notably colistin, and the treatment often involves colistin combination therapy. This increased resistance has the potential to lead to new outbreaks or prolong existing ones.

Dr. Olson says this newfound resistance may not have a direct impact on ophthalmology, but notes it’s still a disturbing development. “We generally categorize resistance as an overuse-of-antibiotic issue and not an antiseptic issue,” he says. “Clearly, this information shows that chemical resistance can be just as troubling. These results aren’t surprising so much as they are concerning. However, because chlorhexadine is so toxic to the ocular surface, it’s very seldom used in ophthalmology. Povidone-iodine is used 99 percent of the time, so unless they show PI has the same problems, I don’t think this is a big issue for ophthalmology. It is, however, a huge concern for medicine in general.” REVIEW

1. Wand M, Bock L, Bonney L, et al. Mechanisms of increased resistance to chlorhexidine and cross-resistance to colistin following exposure of Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates to chlorhexidine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. doi:10.1128/AAC.01162-16. Epub ahead of print. Accessed 21 Nov 2016.