Whether a patient has keratoconus, ectasia following refractive surgery, or pellucid marginal degeneration, corneal collagen cross-linking can be used to prevent progression. This treatment is a particularly safe and effective procedure, and rarely do complications arise. However, complications can occur, and some patients may experience negative effects, vision-threatening symptoms as well as continuous progression. Here, experts share their knowledge on what complications may arise following CXL and how to manage patients.

Complications and Their Management

There are several complications that can present postoperatively. Some are far more common and don’t pose as much of a threat compared to others. In most cases, these problems can easily be treated with topical drugs and contact lenses, but severe cases may need to be retreated with CXL or could lead to a corneal transplant. “Most of the side effects—complications of cross-linking—are really related to epithelial removal,” says Peter Hersh, MD, of Teaneck, New Jersey, and the U.S. medical monitor of the original CXL FDA trial by Avedro, which was acquired by Glaukos in 2019.

• Ocular pain. Common amongst invasive surgeries, patients do experience pain and discomfort following CXL due to the epithelial debridement. The epithelium-off CXL technique is the only technique approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Although pain isn’t touted as a complication, it’s best to ensure that patients are satisfied through this process and given proper care for any irritation that may arise.

“There’s expected pain, which I wouldn’t call a complication, and it could worsen, which I wouldn’t call a complication either,” suggests Brad Feldman, MD, a cornea and refractive surgeon at Philadelphia Eye Associates in Pennsylvania. “Most patients have pretty well-tolerated pain that they’re able to sleep off in the first several hours after the procedure, and by the next morning, they’re no longer in pain. They just have some mild discomfort, tearing or foreign body sensation, but there are some patients who have more intense or prolonged pain, as well as folks who have no initial pain and develop it at day two or three. That’s pretty uncommon, but it can happen.

“So, for people who have very sensitive eyes, it’s just a matter of giving them NSAIDs topically, maybe getting them a pain medication beyond just ibuprofen or acetaminophen,” he continues. “It’s pretty rare that I would prescribe a narcotic, but maybe I’ll prescribe one once every couple of years. Then, there’s the people who are doing fine and they start having pain a few days later, and the most common cause of that would be the contact lens falling out and not being noticed by the patient, or tight lens syndrome, where they start to swell up and get a keratitis from that. In that case, we just swap the lens out for a looser one.”

|

|

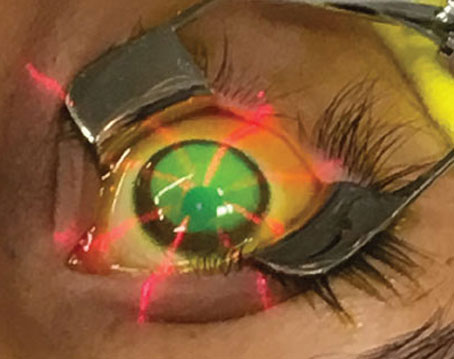

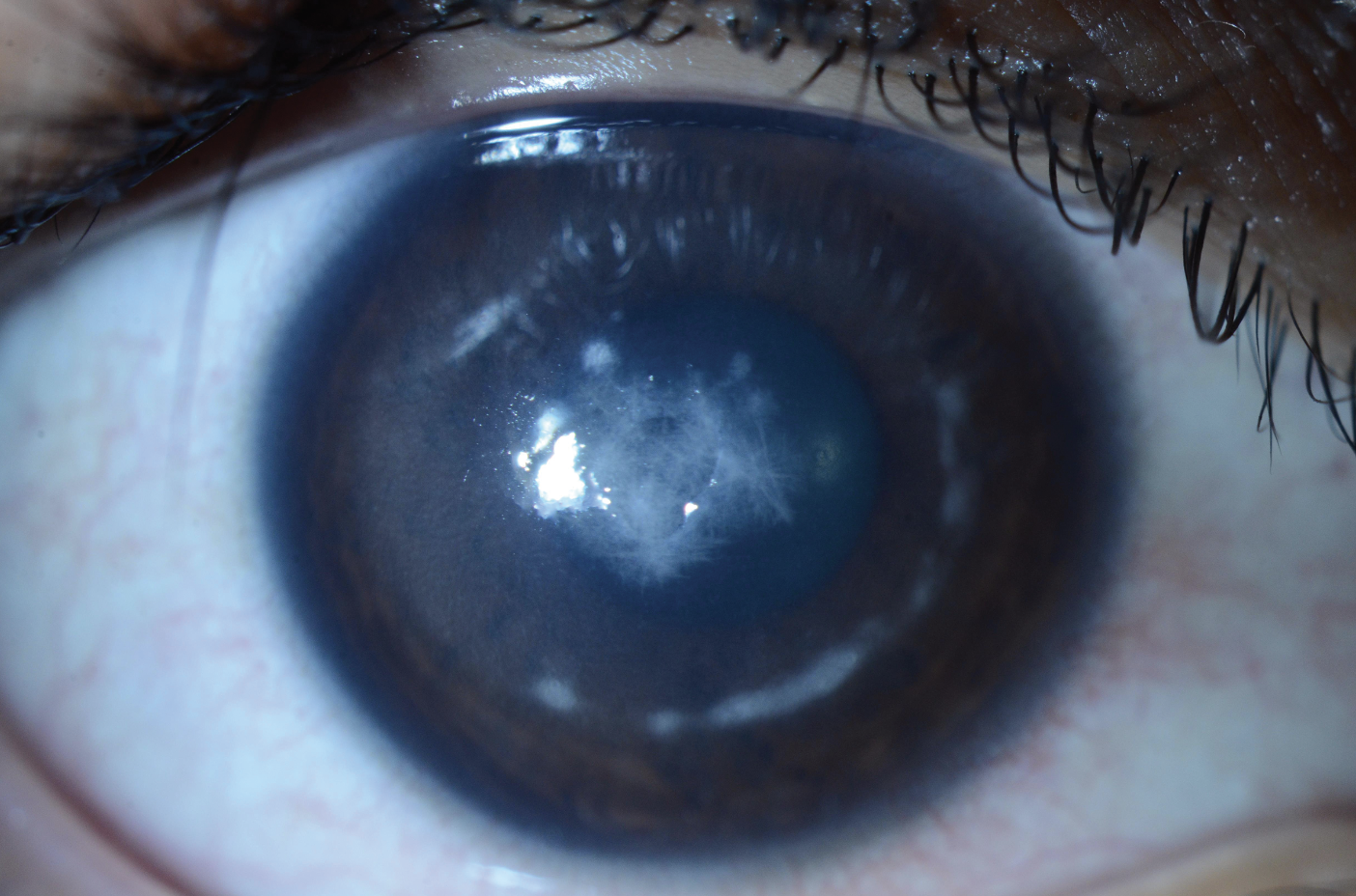

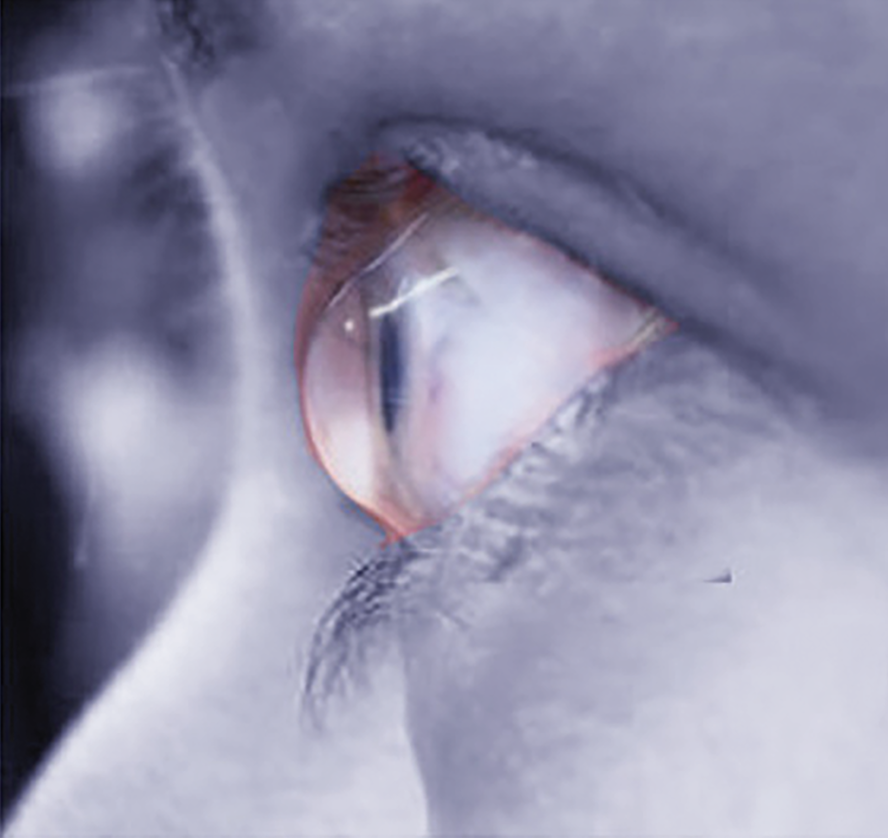

An eye presenting with infectious keratitis four weeks after cross-linking. If infection persists to severe stages, then a corneal transplant may have to be employed. Photo: Zeba Syed, MD. |

• Delayed epithelial healing. Similar to ocular pain in the sense that it’s one of the earliest complaints a patient has following CXL, delayed reepithelization, if not treated properly, can lead to more severe complications, but these cases are rare.

“Delayed epithelial healing can occur due to many reasons, such as age, steep corneas, poor hygiene, poor compliance with medication, pre-existing ocular surface disease and more,” explains Joann Kang, MD, a cornea and refractive surgeon at the Montefiore Medical Center in New York. “Delayed epithelial healing then in turn puts a patient at risk for other complications.” This is one of the more frequent complications that arises following CXL, with rates varying between 4 and 26 percent, depending on the literature.1 She notes that, if the wound from removing the epithelium doesn’t heal correctly, then it can result in permanent visual sequelae.

“In the early stages after cross-linking, the most common thing to see would be a delayed wound healing,” adds Steven Greenstein, MD, who practices with Dr. Hersh. “So generally, we see that the epithelium heals somewhere between three to four days. It heals mostly because a high volume of patients are pretty young. We generally will take out a bandage contact lens at about five days for these patients, and rarely you’ll see a slower wound healing where they still have an epithelial defect. Even with those, I would say most tend to heal with minimal additional intervention, but sometimes they do need things like serum tears or even amniotic membrane to help them heal. It’s extremely rare to see infection with it. I can count on one hand the number of cases we’ve seen over the course of a decade that we’ve done cross-linking.”

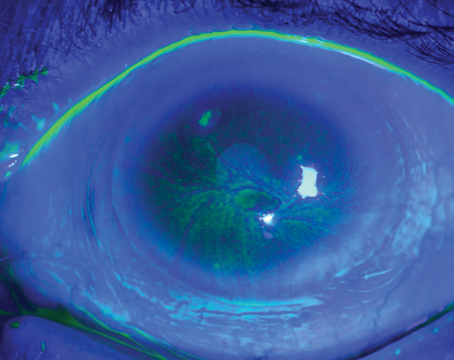

• Corneal haze. “One of the things that we most noticed as a general event after cross-linking is a cross-linking associated corneal haze,” says Dr. Hersh. Corneal haze is an effect that occurs in most patients but isn’t always described as a complication.

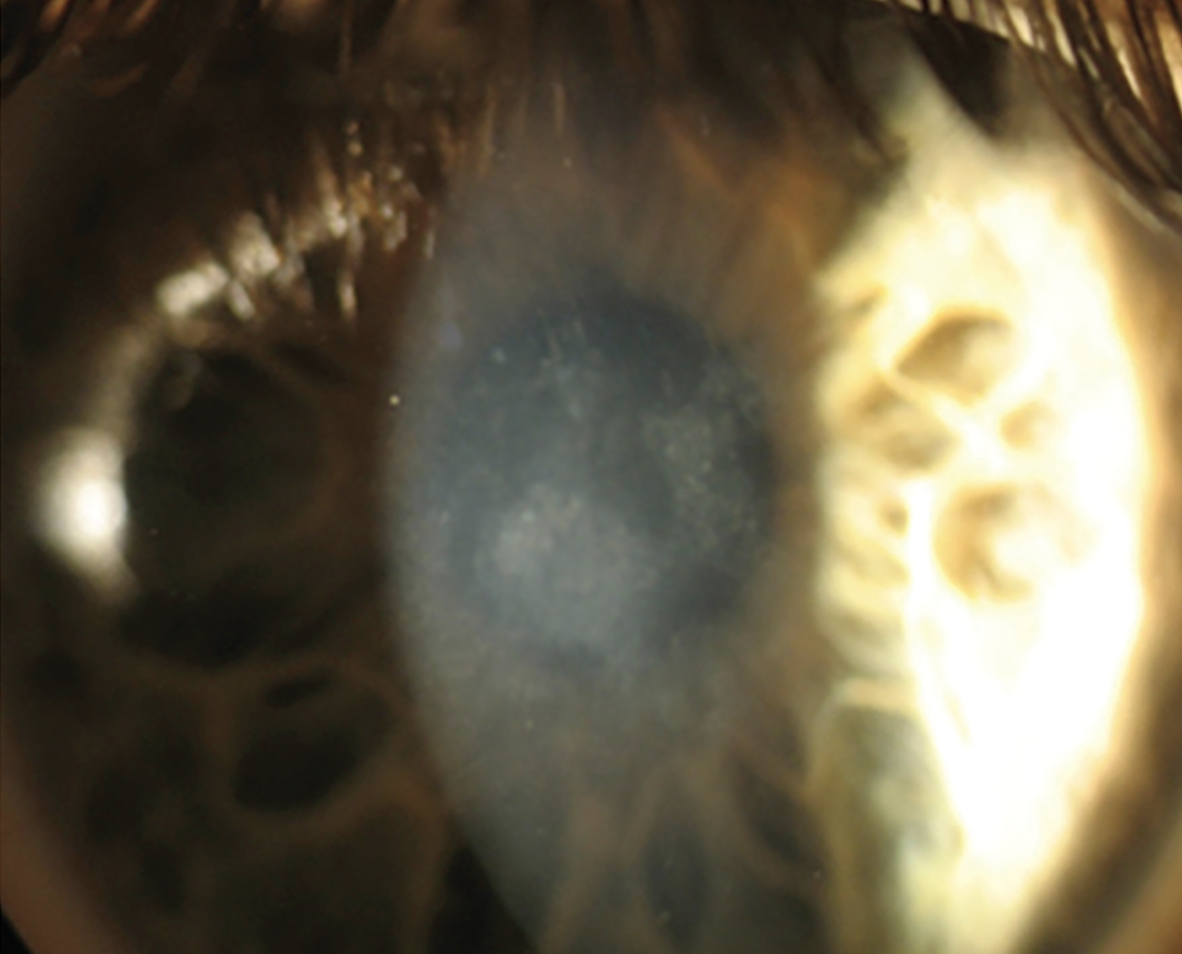

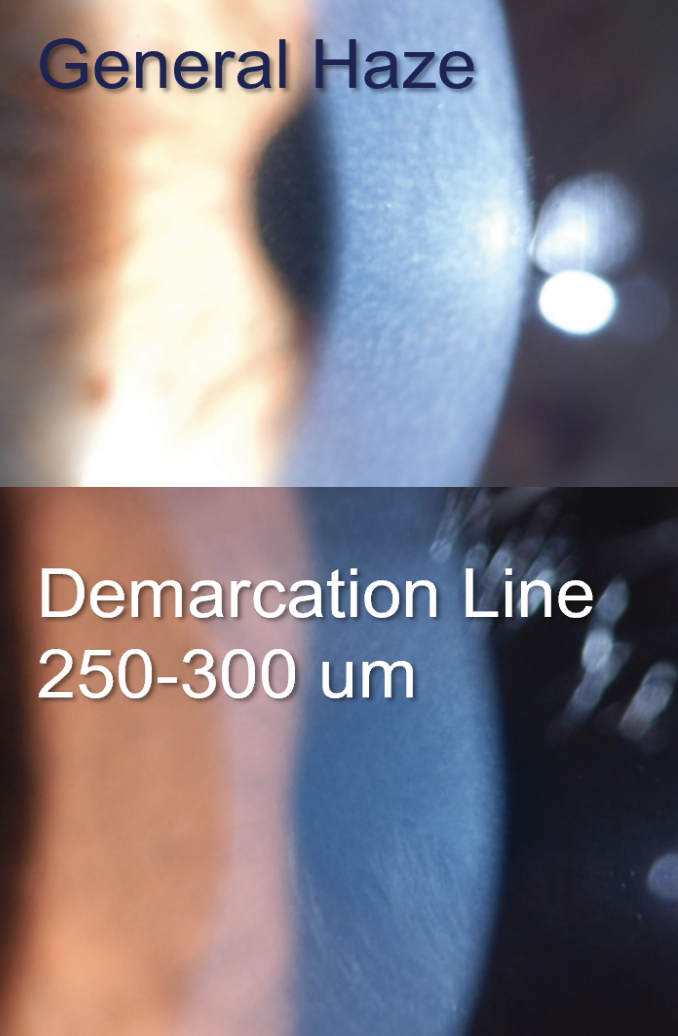

“Most patients who undergo cross-linking initially develop a generalized haze in the anterior corneal stroma soon after the procedure, and then this tends to evolve into what we call a demarcation line,” Dr. Hersh explains. “If you look carefully under the slit lamp or with OCT, you can see a little bit of haziness down to the area of cross-linking, and this demarcation line delineates really the area of cross-linked tissue from the area of non-cross-linked tissue posteriorly. Typically, with a standard procedure, this is about 250 or 300 microns deep.

|

| A slit-lamp photograph of a patient’s left eye with deep corneal haze. Although not seen as a complication, haze can progress late after cross-linking and cause further issues to arise. (Creative Commons License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.) Photo: Peponis V, et al. |

“Now, what we find with the cross-linking associated haze is that it peaks in a month, it plateaus at three months, and then it returns to baseline,” he continues. “Typically, it goes back to baseline by the first year. It’s very important that the ophthalmologist recognizes this, and we always will advise the patient that this haze will generally subside over time.”

Both Drs. Hersh and Greenstein were a part of clinical trials for corneal cross-linking, and they published a study in the early days of the procedure which reported that 90 percent of eyes that were cross-linked experienced stromal haze.2 If there are so many patients presenting with this, then why should it be seen as a complication?

|

| The demarcation line seperates the area of cross-linked tissue from the area of non-cross-linked tissue posteriorly in a case where haze is present. Photo: Peter Hersh, MD. |

“It’s always been a big debate whether haze is even a complication at all,” explains Dr. Greenstein. “It’s important when you talk about haze in cross-linking to really distinguish the type of haze that you expect to see. We did a lot of early work and published papers in terms of the natural course of haze, which tends to increase to its peak and then generally returns to baseline somewhere between six months and a year. That we don’t really consider it a complication. In fact, in some ways, we view that as the cross-linking taking effect and working.

“On the other hand, a longer-term haze, which kind of leads to more corneal stromal scarring, is certainly a rare complication that you can see with cross-linking in the later phases somewhere between three months and a year down the road,” he adds. The standard postop regimen for CXL at Drs. Greenstein and Hersh’s clinic includes a combination of antibiotics and steroid drops, which are tapered over three weeks. But, in cases of long-term haze, Dr. Greenstein notes that they extend the steroid taper and try to limit any inflammatory response that may be seen.

“More recently, we’ve tried topical losartan, which we’ve compounded,” Dr. Greenstein adds. “There’s been some early studies that have shown that that might be effective in corneal scarring. We haven’t seen it work that well post-cross-linking, but we have tried that as an option.”

• Corneal scarring. This complication is tricky. Some patients may present with scarring before the CXL procedure, and some may develop scarring afterwards. In one study, the incidence of scarring was reported to be 2.9 percent.3 As explained earlier, scarring can occur due to long-term haze in patients, and losartan can be employed to treat this, although it’s used off-label.5

What ophthalmologists need to be aware of is that pre-existing corneal scarring is seen as a contraindication for CXL and can increase the risk of further complications following the procedure. “Assess the thickness of any pre-existing scarring because this may lead to a greater incidence of haze or scarring after the procedure,” notes Dr. Hersh. “Patients who have central scarring might require a corneal transplant, and patients who have more peripheral scarring, where the risk of haze might be somewhat increased, [should be seen as a contraindication].”

“We know that if we treat people who have scars in the cornea, they’re more likely to develop haze, and I typically won’t treat those patients with cross-linking,” adds Dr. Feldman. “Instead, depending on the size of the scar, we either offer scleral or specialty contact lenses alone, or if it’s a dense scar that the patient can’t see well out of, then we can do a corneal transplant.”

• Infectious keratitis. Infections can be caused by a whole host of reasons and should be avoided if possible. Cases of infection are rare, but they’re seen as one of the most dreaded complications to arise following CXL, according to Praneetha Thulasi, MD, an assistant professor of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and a cornea specialist at the Washington University Eye Center. In a large population study, researchers found that infection occurs in 0.12 percent of cases.6

“[At our practice], we treat patients with steroids postoperatively,” says Dr. Thulasi. “With cross-linking and steroids, patients do have sort of an immunosuppressed state. So, infectious keratitis is the thing that we worry the most about. It’s fairly rare. It’s usually related to some sort of patient compliance issue, but I’ve done this for nine years now, and I’ve seen this in three cases. Only one patient had a really severe infection to the point where we needed to do a corneal transplant.

“[Infectious keratitis] could be from possible contamination during the surgery,” she continues. “These aren’t technically sterile procedures. They’re what we call ‘clean procedures.’ So, surgeons aren’t doing them in the operating room. It could be from the fact that we put a contact lens on the patient for postoperative pain management. It could be from patients not using antibiotics after treatment. Also, the few patients I’ve had were all young folks who had trouble putting drops in. It could’ve stemmed from that. I don’t think we have a definitive answer as to what causes these infections, but those are all the things we look at any time we have a complication.”

Zeba Syed, MD, a cornea and refractive surgeon at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia, makes a procedural plan with her team prior to CXL to avoid infection and treat it if it occurs after the procedure. “I always use povidone-iodine to cleanse the eyelids prior to cross-linking and minimize the risk of eyelid flora resulting in infectious keratitis,” she says. “My team members involved in the procedure always wear masks while cross-linking to reduce the chances of oral flora contaminating the surgical field. An antibiotic drop is placed at the conclusion of the procedure, and patients are advised to start antibiotic treatment immediately afterwards.

“These infections are cultured, and the patients are started on fortified antibiotics, and culture results will guide more targeted therapy,” she continues. “I’ll typically discontinue any corticosteroid drops until culture results return or the clinical picture starts improving.”

What both Drs. Thulasi and Syed are alluding to are bacterial infections that may occur after the procedure, but there are other causes. Fungal infections are also a rare possibility that may occur following CXL. “Typically, our first-line drug would be a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone [to treat infection], but I think it’s also particularly important to look for unusual organisms in some of these patients,” suggests Dr. Hersh. “We’ve found in our practice a couple of fungal infections after cross-linking. So, one needs to be wary of that kind of infection as well. You certainly should recommend first, a genetic culture and sensitivity, including a fungal culture and, secondly, if there isn’t a good response to antibiotics, perhaps re-culture and consider a fungal infection.

“Fungal keratitis has been the most severe complication that we saw [in clinical trials], but is that directly affected by the cross-linking? If the epithelium isn’t completely smooth and healed, those patients are more prone to infection. Certainly, if they’re also on prolonged steroid treatment, they’re more susceptible to infection, particularly the possibility of fungal infection. Again, fungal infection is very rare, but it’s one of the more unusual things that we have seen.”

Additionally, it should be noted that herpes simplex keratitis can cause infection and should be noted as a contraindication for CXL. “Anybody with a history of viral keratitis, particularly herpetic keratitis, we know any procedure can trigger recurrence of that virus again, and they’ll have delayed healing as well,” adds Dr. Thulasi.

|

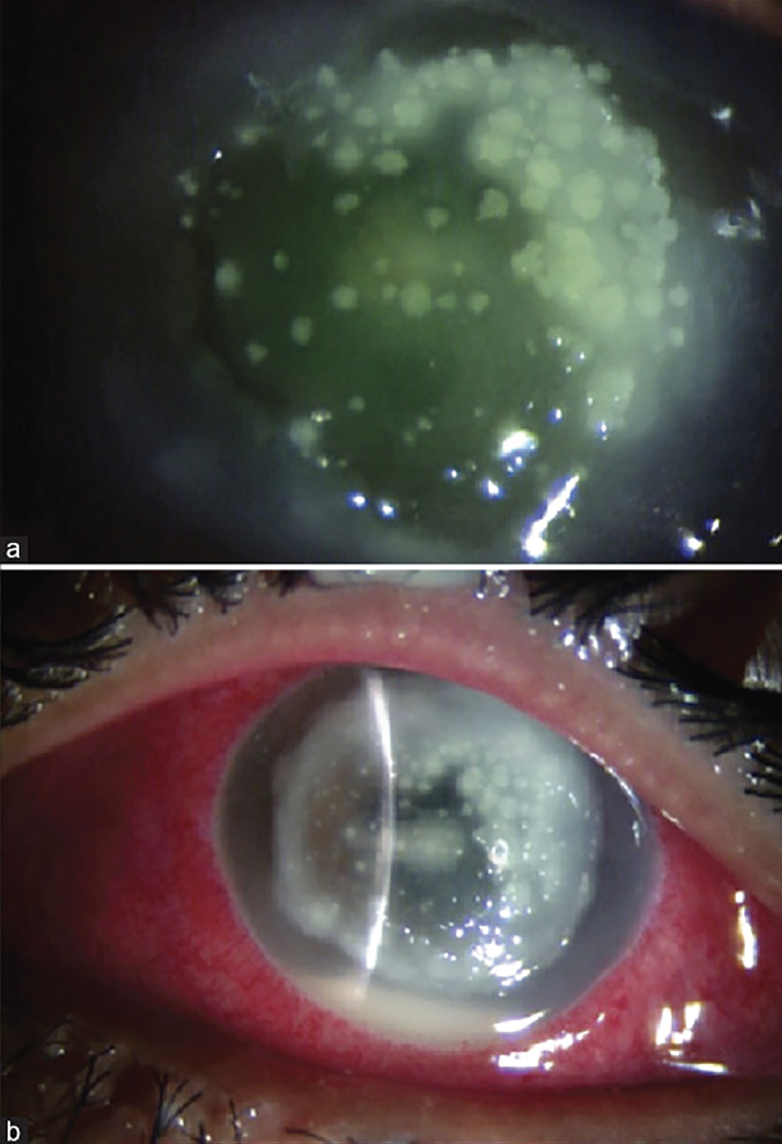

| Corneal melt presenting in a 15-year-old patient post-CXL. (A) Patient’s eye with diffuse infiltrates three days postop. (B) Patient’s eye with corneal melt six days postop. They were treated with penetrating keratoplasty. (Creative Commons License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.) Photo: Agarwal R, et al. |

• Corneal melt. In some cases of infection, the patient may progress to having a corneal melt. “In severe infections, if the patient isn’t improving or they progress to having a corneal perforation or melt, we may need to do a corneal transplant, but severe infections are generally pretty rare,” says Dr. Thulasi.

Corneal melt can be induced by NSAIDs prescribed to patients for a presenting epithelial defect.4 This treatment, along with others, can produce changes in the cornea which increase the risk of melt and perforation. There are ways to reduce the epithelial defect and mitigate the risk of corneal melt.

“In these cases, I’ll typically place amniotic membrane in the clinic to help reduce inflammation and promote epithelialization,” says Dr. Syed.

• Disease progression. Sometimes conditions such as keratoconus progress following surgery. The experts in this article tend to see a younger patient population for CXL, therefore these patients’ corneas are still progressing naturally as they get older. While CXL is meant to prevent further progression of corneal diseases, the condition can relapse due to patients’ changing corneas.

“In cases of disease progression, repeat cross-linking is usually indicated,” says Dr. Syed. “I counsel patients who’ve been cross-linked that even though they’re now at a decreased risk of progression, they should still avoid rubbing their eyes because progression is possible. Increased rates of progression after cross-linking typically occur in younger age groups.”

The incidence of disease progression for keratoconus is staggeringly lower than the rates of progression for other diseases. For keratoconus, CXL is quite successful, with only a 7.6 percent failure rate according to one study.7 In another study looking at the disease progression three years after treatment for both keratoconus and post-LASIK ectasia patients, keratoconus progressed in 5 percent of subjects, while ectasia progressed in 25 percent of subjects.8

If the patient begins to complain about their disease progression and how it’s affecting their vision, then moving forward with another treatment option could satisfy them. “Contact lenses, particularly the new scleral lenses for keratoconus are very helpful in patients who don’t have good spectacle-corrected vision, and then there are a number of surgical procedures that are now available,” shares Dr. Hersh. “One of the things that we’re particularly interested in is what we called CTAK, or corneal tissue addition keratoplasty, in which we use a shaped allograph to preserve corneal tissue in order to improve corneal topography and vision. But that’s really separate and distinct from the need for retreating for progression.”

Pearls for CXL

|

| Corneal collagen cross-linking was approved for keratoconus in 2016, and has been effective in treating cases in the center and periphery of the cornea. Also, it’s able to treat other peripheral conditions such as pellucid marginal degeneration. (Creative Commons License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.) Photo: S. Bhimji, MD. |

There are ways to mitigate complications following CXL. While precautions can be made to avoid infection by keeping the procedure sterile, evaluation of each patient prior to treatment can help avoid any surprises that may occur.

“Good patient selection and preoperative comprehensive discussion with patients regarding risk/benefits [helps prevent complications],” says Dr. Kang. “I discuss in detail what to expect and the importance of follow-up and adherence to treatment recommendations.”

Dr. Hersh shares how his clinic selects the right patient for CXL. “What you want to do is evaluate the ocular surface and any ocular surface disease should be treated [prior to cross-linking],” he says. “This includes dry eye, blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction. So, we recommend a complete ocular surface examination and observe tear breakup time and perhaps look at imaging of the tear film. Some people will also use tear-film osmolarity. So, we recommend that any ocular surface, dry eye, tear film abnormality or blepharitis be treated beforehand. I think this is one of the most important things in preventing a complication.”

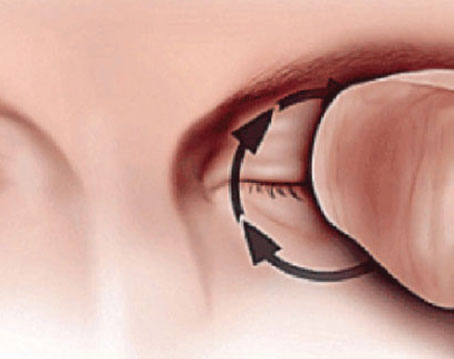

In some cases, adjusting the position of the UV light can help, but ensure that the limbus is protected when cross-linking the periphery of the eye. “Sometimes for very peripheral cones, we might de-center the UV light somewhat toward the periphery of the cornea. Although there hasn’t been enough proven data that that affects the limbal stem cells, you’re clearly shining more of the UV light in that area, so sometimes we’ll place a limbal protector around that area to prevent the light from hitting it, but that’s for specific cases. We don’t do that across the board.” He notes that post-LASIK ectasia patients sometimes present with peripheral cones, in which case he’ll de-center the UV light and add protection to the limbus.

After the procedure, there are a host of options to avoid complications. For instance, Dr. Feldman provides his patients with UV light-blocking sunglasses and requires patients to wear them for three months after treatment. In addition, physicians try to keep the cornea lubricated, possibly with a bandage contact lens, to ensure re-epithelialization. But Dr. Feldman notes that an epithelial defect may persist even with the presence of a bandage contact lens covering exposed nerve endings, since the epithelium was removed during the procedure.

Talking with Patients

|

| Patients might not understand how cross-linking treats their condition. Ensure each patient is informed about the procedure, its outcomes and any possible complications that may arise. |

Keep in mind that CXL is a relatively safe and effective procedure, but physicians can’t always rely on preoperative and postoperative treatment management. Patients must be made aware of the signs and symptoms of their case as early as possible to alleviate treatment burden. “From a public health point of view, the field would be greatly helped and the loss of vision from keratoconus would be dramatically reduced if patients were recognized early and received proper treatment early on,” states Dr. Hersh.

When a patient walks into the clinic presenting with keratoconus or some other CXL-treated condition, begin a conversation with them. Every physician’s goal is to satisfy their patients’ needs, and that’s reliant on how much the patient complies to the treatment plan.

“The most critical thing with cross-linking is to really drill into patients that this is a stabilizing procedure,” comments Dr. Greenstein. “Patients expect results that’ll improve their situation when they go through a procedure anywhere on the body. So, when it comes to eye procedures, patients are expecting that the procedure is going to improve their vision. While all of our studies have indicated that cross-linking, on average, does slightly improve spectacle-corrected vision, those changes are incredibly small, and for the vast majority of our keratoconus patients, they’re not really noticeable.

“We have other procedures that can help with improving corneal curvature and vision, but the key is to stress the stability component of the procedure and that we don’t expect things to get better from a vision standpoint, or even significantly from a curvature standpoint, simply by doing cross-linking alone,” he continues.

Advancements Towards Safety and Efficacy

Dr. Thulasi says certain advancements are improving CXL and improving the safety and efficacy of the procedure. “There are three groups of people I can think of where we could use advancements,” she explains. “One is to decrease risk of complications of infection and pain. So, epithelium-on cross-linking, at least according to the data that we have so far, shows efficacy. It essentially eliminates any pain. So, that’s something we’re very excited about.

“The second issue is that cross-linking is a really long procedure,” she continues. “It takes an hour and a half during which a patient has to sit in a room. And so, there are accelerated cross-linking and certain variable-fluence cross-linking that do decrease the duration significantly, and that would increase tolerance. It would allow us to do cross-linking on patients such as kids or patients with Down syndrome or other patients where they wouldn’t be able to stay still for about an hour. So, that would really expand the number of patients we could offer this to safely.

“And the third issue is that patients who come in with advanced keratoconus who are already below the threshold of 400 microns don’t have the required corneal thickness for treatment,” she continues. “So, there are some newer ideas out there. One being contact lens-assisted cross-linking, which can artificially boost the thickness of the cornea, so to speak, and prevent complications. There’s also some interesting research on this method. Investigators are individualizing the duration of cross-linking to each person’s corneal thickness and that would certainly allow for effective treatment without ruling all these patients out and letting them progress to needing a corneal transplant. So, those would be the groups that could use these advancements. I think some of these advancements are very exciting in those particular subgroups."

Dr. Hersh is the U.S. medical director for Glaukos and a consultant for Corneagen. Dr. Greenstein consults for Glaukos. Dr. Syed is a consultant for Glaukos. Drs. Feldman, Kang and Thulasi have no related finacial disclosures.

1. And MJ, Darbinian JA, Hoskins EN, et al. The safety profile of FDA-approved epithelium-off corneal cross-linking in a US community-based healthcare system. Clinical Ophthalmology 2022;16;1117-1125.

2. Greenstein SA, Fry KL, Bhatt J, Hersh PS. Natural history of corneal haze after collagen crosslinking for keratoconus and corneal ectasia: Scheimpflug and biomicroscopic analysis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2010;36;12:2105-14.

3. Agarwal R, Jain P, Arora R. Complications of corneal collagen cross-linking. Indian J Ophthalmol 2022;70;5:1466-1474.

4. Wilson SE. Topical losartan: Practical guidance for clinical trials in the prevention and treatment of corneal scarring fibrosis and other eye diseases and disorders. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2023;39;3:191-206.

5. Rigas B, Huang W, Honkanen R. NSAID-induced corneal melt: Clinical importance, pathogenesis, and risk mitigation. Surv Ophthalmol 2020;65;1:1-11.

6. Farrokhpour H, Soleimani M, Cheraqpour K, et al. A case series of infectious keratitis after corneal cross-linking. J Refract Surg 2023;39;8:564-572.

7. Koller T, Mrochen M, Seiler T. Complication and failure rates after corneal crosslinking. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009;35;8:1358-62.

8. Chanbour W, El Zein L, Younes MA, et al. Corneal cross-linking for keratoconus and post-LASIK ectasia and failure rate: A 3 year follow-up study. Cureus 2021;13;11:e19552.