One of the more frustrating refractive challenges for both surgeons and patients, corneal irregular astigmatism can arise from a variety of factors, leading to unpredictable visual outcomes. The irregular curvature of the cornea not only affects visual clarity but also increases higher-order aberrations such as coma and trefoil, resulting in discomfort from glare and halos around light sources. Treatment strategies must be tailored to address the specific underlying causes in order to achieve the best possible results.

Here, experts delve into the intricacies of corneal irregular astigmatism, exploring its causes and the management approaches that enhance patient outcomes.

Highly Irregular

Brian M. Shafer, MD, of Shafer Vision Institute in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, explains that corneal irregular astigmatism is defined topographically when the meridians of astigmatism aren’t perpendicular to each other. “This results in reduced best corrected visual acuity that’s not correctable with glasses or soft contact lenses,” he says. “In regular astigmatism, the meridians are perpendicular to each other, and it’s correctable with optical lenses in front of the eye.”

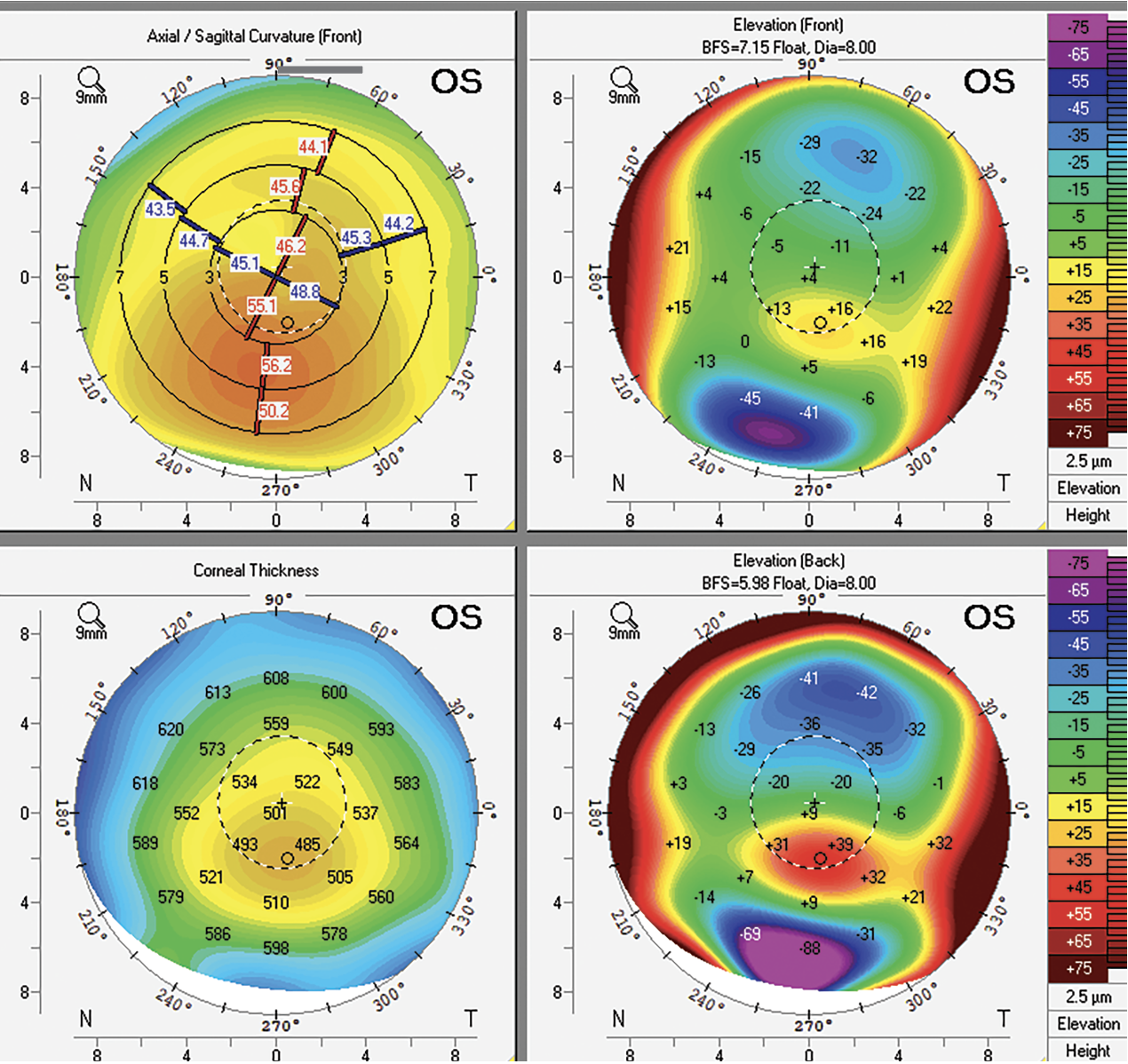

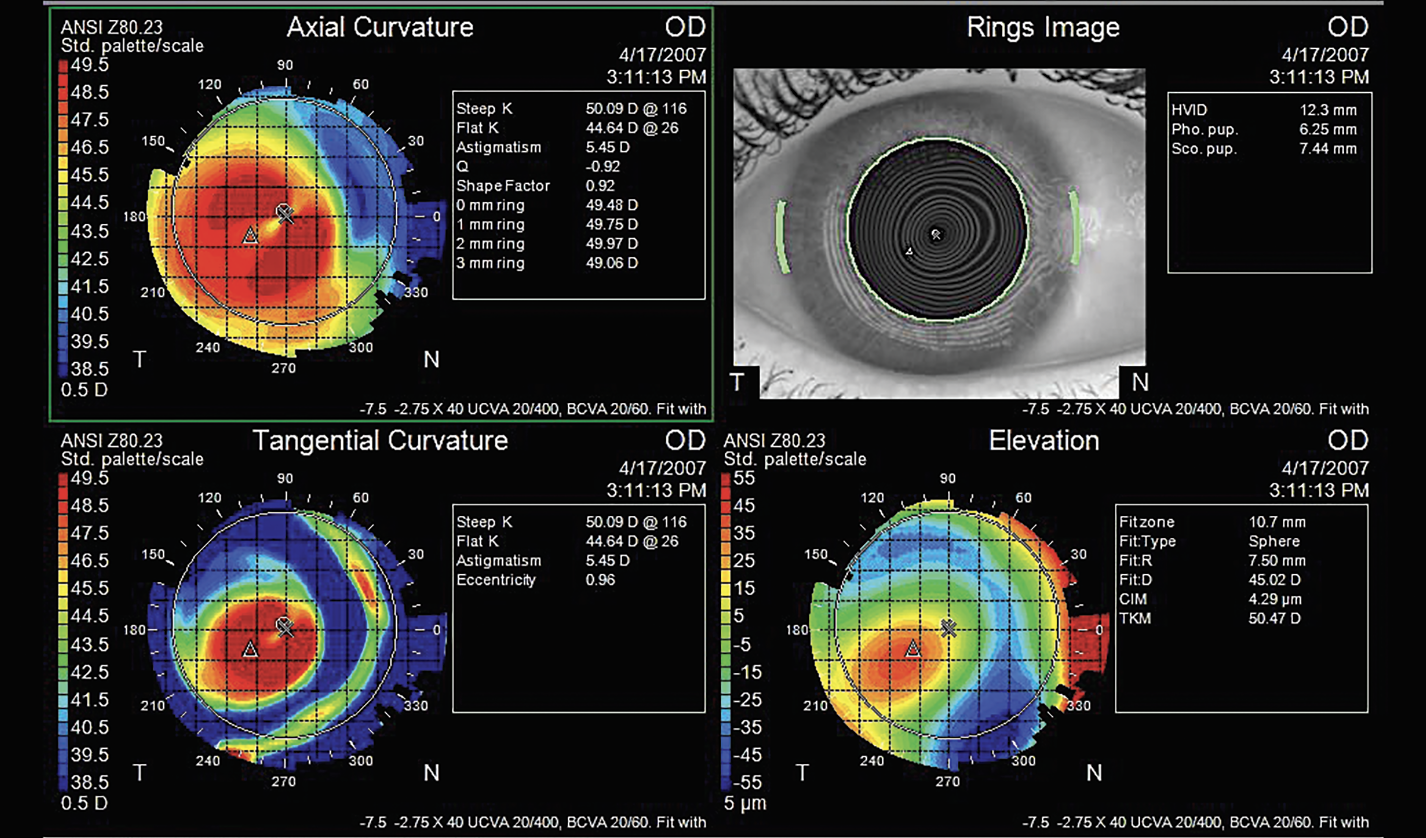

Clinicians rely heavily on corneal topography when assessing irregular astigmatism. “Placido disc imaging is a great technique for assessing the corneal surface, in addition to elevation mapping like the Pentacam,” says Jonathan Rubenstein, MD, Chairman of Ophthalmology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. “Treatment goals vary, depending on the degree of irregular astigmatism and the treatment endpoint. Is the surgeon looking for some degree of improvement in vision or are they looking to provide a patient with functional uncorrected visual acuity? Preoperatively, surgeons need to normalize the cornea enough to make it amenable to astigmatic treatment at the time of cataract surgery. For example, in cataract surgery, we might aim to normalize the cornea so it can be treated with a toric lens that you couldn’t offer before.

“It’s important to discuss treatment options with the patient and explain how far you can go with treatment,” he continues. “Significant irregular astigmatism due to severe scars from trauma or infections often can’t be treated without keratoplasty. Treatment options depend on the degree of corneal pathology.”

|

|

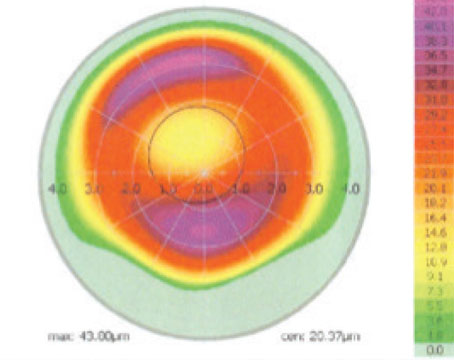

Figure 1. Irregular astigmatism associated with keratoconus, with inferior steepening and thinning. Photo: Brian M. Shafer, MD. |

Key Causes

A variety of conditions and situations can contribute to abnormal corneal shape and irregular astigmatism. Here are some of the causes commonly seen in clinic:

• Corneal ectasia. Ectatic conditions such as keratoconus (Figure 1), pellucid marginal degeneration and post-LASIK ectasia are among the most common etiologies for irregular astigmatism, characterized by irregular thinning, steepening and bulging of the cornea.

• Scarring. Scarring may result from events such as trauma or old infections such as herpes, bacterial infections or fungal infections. “If you have a scar on the cornea from a prior infection, that area becomes very flat after the infection heals and the scar sets into place,” Dr. Shafer explains.

“It’s important to realize that it’s really not the opacity from the scar that tends to decrease vision, but rather the shape change, or irregular astigmatism induced by the scar that causes decreased visual acuity,” Dr. Rubenstein notes.

• Prior RK. Radial keratotomy flattens the central cornea to improve vision by creating multiple incisions. Irregular astigmatism can result from the RK incision scars. Though it’s not performed anymore, having fallen out of favor in the wake of newer, more predictable refractive procedures like LASIK, Andrea Blitzer, MD, of NUY Langone’s Department of Ophthalmology, says that “many patients who had RK in the 80s are now experiencing hyperopia, astigmatism or scarring of the cornea, causing further astigmatism.”

|

| Figure 2. Dry eye is one of the most common and fixable causes of irregular astigmatism. Treatments targeting tear production and the lids may help, depending on the type of dry eye. Photo: Jonathan Rubenstein, MD. |

• Ocular surface disease. “Various disease entities can damage the tear film,” Dr. Rubenstein says. “Ocular surface disease, and more specifically dry eye, is probably the most common cause of irregular astigmatism in my practice (Figure 2). An irregular surface causes degraded optics, poor visual acuity and the inability for the accurate assessment of corneal power that’s required for lens implant calculations before cataract surgery.

“With ocular surface disease, we’re looking at three components of the tear film which may be altered: the aqueous component; the oil component; and the mucus component. The aqueous component can be altered in all sorts of conditions that cause dry eye, from common causes such as aging and reduced aqueous production to decreased blink rate related to driving, or staring all day at computers, cell phones and TVs.

“Chronic meibomian gland dysfunction affects the oil component of the tear glands,” he continues. “Anything that can affect the ability to produce a normal oil layer on the outside of the tear film can result in chronic ocular surface disease from evaporative dry eye. The third component is mucin. Mucus comes from goblet cells in the conjunctiva. Scarring of the conjunctiva, for example, leads to decreased goblet cell density. This leads to decreased mucus formation, which destabilizes the tear film.”

• Epithelial abnormalities. Conditions such as epithelial basement membrane dystrophy can lead to irregular astigmatism, though typically not to the same degree as something like ectasia or scarring. “In EBMD, there’s redundancy in the basement membrane and the epithelium is irregular, which on its own can create some irregular astigmatism,” Dr. Shafer says.

|

| Figure 3. Irregular astigmatism resulting from Salzmann’s nodules. Photo: Jonathan Rubenstein, MD. |

• Salzmann’s nodules. “These can grow anywhere on the cornea,” he says (Figure 3). “They typically start in the peripheral or mid-peripheral zones and lead to irregular astigmatism.”

• Pterygium. “A pterygium typically grows in from the nasal aspect of the conjunctiva and may cross into the central visual axis, creating flattening in that area and inducing irregular astigmatism,” he says (Figure 4).

Optical Strategies

If the patient has a low amount of irregular astigmatism, spectacles are a non-invasive treatment worth trying. However, clinicians say it’s common for patients to remain unsatisfied with this management approach. When it comes to lens-based strategies for irregular astigmatism, hard contact lenses1 and pinhole IOLs are the go-to for many doctors.

“A soft contact lens might neutralize some irregular astigmatism, if it’s a mild amount, and particularly if it’s a lens with a more rigid modulus, such as a silicone hydrogel lens. But typically, irregular astigmatism requires a rigid lens of some sort,” says Deborah S. Jacobs, MD, of Massachusetts Eye and Ear.

“I think most corneal specialists have been in a situation where they originally thought a patient had such a large degree of irregular astigmatism or corneal scarring that the only treatment was keratoplasty, but instead found that when the patient was fitted with a scleral contact lens, they achieved an excellent level of visual acuity,” Dr. Rubenstein says. “The advances that have occurred in hard contact lens design—with computer programs that design the contact lens fit to the development of scleral lenses—have really helped to treat irregular astigmatism and have offered many potential surgical patients a non-surgical alternative treatment.”

Scleral lenses and RGP lenses work by masking the irregular surface of the cornea. “The refractive element of the cornea is really the cornea-tear film interface,” explains Dr. Shafer. “Functionally, [these lenses] create a normal surface that can bypass the irregularity and allow the patient to see more clearly when you correct their manifest refraction as well.”

Scleral lenses are useful options for rehabilitating eyes with conditions such as keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration and after penetrating keratoplasty. “They’re more predictable than incisional surgery to correct irregular astigmatism and may be more appropriate for some patients than PRK or LASIK,” says Dr. Jacobs.

These lenses are typically used as a treatment for bilateral problems. Dr. Jacobs says that it’s rare for patients to tolerate a rigid lens in just one eye. “If the irregular astigmatism is the after effect of trauma or surgery or an infection, and it’s affecting only one eye, then the patient is much less likely to accept or adapt to wearing one contact lens,” she says. “In these cases, surgical or laser approaches make more sense. That said, a rigid scleral lens might fare better [than a rigid corneal lens] if it’s well-fitted.”

Dr. Rubenstein adds that hard contact lenses are also an important diagnostic modality to assess the effects of irregular astigmatism on visual acuity, since the irregularities can be masked with a hard contact lens. “You can place a hard contact lens on the patient in the office and see if that improves their acuity,” he says.

In addition to rigid lenses, surgeons now have the opportunity to manage irregular astigmatism with a small-aperture intraocular lens implant, the Apthera lens (formerly the IC-8). “This lens works via the pinhole principle,” Dr. Shafer says. “It bypasses some of the irregularity by filtering out the scattered light and only letting through the focused light. This can help correct some of the aberrations induced from irregular astigmatism.”

Ectasia

Before turning to optical correction for the irregular astigmatism induced by ectatic conditions such as keratoconus, pellucid marginal degeneration and post-LASIK ectasia, surgeons often perform corneal collagen cross-linking. “This procedure strengthens the cornea to prevent it from progressing and becoming more cone-shaped, but it doesn’t fix the irregular astigmatism that’s already occurred—it’s more of a way to halt further progression,” Dr. Blitzer says.

The decision to cross-link before or after a procedure “is a philosophical question that will differ from surgeon to surgeon,” Dr. Shafer says. “My personal approach at this point in time is to cross-link the patient first, wait six months, and then place ring segments, just because we know that the cornea does change a little bit after cross-linking. I like to see it stabilized before doing something like [ring segments]. However, there are surgeons who perform ring segments first and then cross-link the patient later. I think that’s totally reasonable also.”

Dr. Blitzer says she prefers to cross-link the patient as soon as indicated. “It’s really important to halt the progression, so as soon as I see a patient who’s progressing with keratoconus and they have no contraindication to getting cross-linked, I recommend that as an early procedure.

“After cross-linking, I recommend contact lenses for many of these patients as well,” she continues. “Much of the irregular astigmatism that we see, including with keratoconus, can be improved with RGP lenses and scleral lenses. These can provide good quality vision.”

Some corneas are too cone-shaped for contact lenses or may need additional flattening before glasses or contact lenses can be used to correct the refractive error. Procedures involving implantable corneal ring segments flatten the cornea and may help stave off the need for a future transplant procedure.

Some options include artificial implants such as Intacs, corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments and a new procedure called corneal tissue addition keratoplasty. “Artificial ring segments, which are made out of PMMA, are placed underneath the area of the ectasia to reinforce it and help correct irregular astigmatism,” Dr. Shafer says. He notes that implant extrusion is one complication to be aware of, which can occur with further stromal thinning or ring migration and leads to chronic pain and discomfort for some patients.

The corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments procedure, developed by Soosan Jacob, MS, FRCS, DNB, employs donor corneal tissue instead of synthetic implants to flatten the cone and improve vision. Since 2018, customized CAIRS has tailored the tissue based on the patient’s unique features, including keratometry and pachymetry, allowing for improved visual outcomes.2

Corneal tissue addition keratoplasty is an emerging allogenic inlay procedure for keratoconus. “Custom femtosecond laser-cut tissue segments, created based on a patient’s Pentacam or tomography imaging, are implanted into a femtosecond laser-cut channel in the host cornea,” says Dr. Shafer. “The goal is to bolster some of the area that’s irregular so you can move it more centrally and make the meridians more perpendicular to each other, therefore making the astigmatism more correctable with glasses or soft contact lenses.”

The results of a prospective CTAK clinical trial (NCT02649738)3 published last year in the Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery report improved visual acuity and topography in patients with keratoconus and ectasia. The single center study involved 21 eyes of 18 patients, each of whom received a custom-cut tissue inlay of preserved corneal tissue. The study reported a significant improvement in uncorrected distance visual acuity from 1.21 ±0.25 logMAR to 0.61 ±0.25 logMAR (Snellen equivalents: 20/327 to 20/82). Corrected distance visual acuity improved significantly from 0.62 ±0.33 to 0.34 ±0.21 logMAR (Snellen equivalents: 20/82 to 20/43). Average MRSE improved significantly as well, and the researchers reported that 20 eyes gained more than two lines of UDVA, 10 eyes gained more than six lines and no eyes grew worse. Twelve eyes gained at least two lines of CDVA and one eye worsened by more than two lines. At six months, the researchers reported an average Kmean flattening of -8.44 D (p=0.002), Kmax flattening of -6.91 D (p=0.096) and mean Kmaxflat of -16.03 D.

Dr. Shafer recently completed his first CTAK procedure. “Procedurally, it’s similar to doing an intracorneal ring segment implantation, but requires a bit more nuance since it’s not as rigid of a segment,” he explains. “I’m excited to be offering this to more patients.”

When a patient’s ectasia is too severe for options such as crosslinking or ring segments, a cornea transplant may be necessary. “Keratoconus does very well with deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, because typically, unless the patient has had an episode of acute hydrops, the posterior cornea is relatively normal,” Dr. Blizter says. “A DALK is preferred, but a penetrating keratoplasty is another reasonable option.”

According to retrospective study of long-term keratoplasty outcomes for keratoconus, DALK resulted in higher endothelial survival and lower risk of postoperative ocular hypertension than PKP.4

|

|

Figure 4. Pterygium in the right eye of a patient. Photo: Jonathan Rubenstein, MD. |

Corneal Scars

“If a scar is causing astigmatism, it can be treated with either a laser or surgical modality,” Dr. Rubenstein says. “If it’s a superficial scar, it can be treated with a mechanical superficial or phototherapeutic keratectomy. If it’s deeper, it might warrant an anterior lamellar keratoplasty; if it’s deeper still, a deep lamellar keratoplasty. If the entire cornea is affected, then sometimes you might have to do a penetrating keratoplasty.”

For corneal ulcers and scars from prior infections, Dr. Blitzer urges caution when performing procedures such as topography-guided LASIK or PRK. “I’d hesitate to do any ablative surgery on those eyes,” she says. “However, these patients would still be good potential candidates for contact lenses and for DALK or PKP if needed.”

Radial Keratotomy

Today, clinicians are managing the late-stage complications of RK. “Some patients do well with contacts, but many of them are also at cataract surgery age, and if their astigmatism in the center of the cornea is relatively regular, they may do well with a toric intraocular lens,” Dr. Blizter says. “The Apthera is another option.”

“The ideal patient [for the Apthera lens implant] has irregular corneal astigmatism, either from perhaps a previous keratoplasty or keratoconus,” Dr. Rubenstein says. “The best patients seem to be those who had previous radial keratotomy. Radial keratotomy can cause all sorts of funny aberrations, especially those who had RK years ago with more and longer incisions. I’ve found that the Apthera is a real advantage for these patients.”

Ocular Surface Disease

Dry eye is a common culprit for irregular astigmatism, and it’s important to treat the root cause. “You have to figure out which part of the ocular surface is affected and what the cause is,” Dr. Rubenstein says. “We’re basically talking about tear film deficiency. So, you have to break it down into its components. Is it an aqueous deficiency? Is it a mucin or mucus deficiency? An oil deficiency? How you treat it depending on the etiology.

“If it’s more aqueous-deficient, try to increase use of artificial tears or anti-inflammatory drops,” he continues. “You can stimulate tear production, perhaps with some of the newer entities like Tyrvaya, for example, or you can block tear outflow with punctal occlusion in various ways. If it’s more of an oil-related etiology, options include performing good eyelid hygiene or using different approaches to physically remove the excess eyelid oil and debris. Some treatments mechanically try to evacuate the oil glands. If it’s a mucus problem, then it’s usually due to conjunctival scarring which can be harder to treat other than with replacement of a more viscous artificial tear.”

Other Corneal Conditions

“Other pathological entities that cause irregular astigmatism are epithelial basement membrane disorders, such as epithelial basement membrane dystrophy or epithelial basement membrane abnormalities,” says Dr. Rubenstein. “These lead to an irregular basement membrane and an overlying irregular corneal epithelium that’s thrown into slight folds, resulting in an irregular surface.” These patients are treated with debridement plus superficial keratectomy with diamond burr polishing.

“If the irregularity is related more to corneal roughness of the surface than a specific dioptric optical feature, one option would be a phototherapeutic keratectomy, which can serve to regularize an irregular surface,” Dr. Jacobs says. “A customized excimer ablation or topography- or wavefront-guided ablation are other options.”

Like PTK, superficial keratectomy also addresses a variety of ocular surface disorders,5 including EBMD.6 Salzmann’s nodules are another condition benefiting from superficial keratectomy. “The epithelium is removed, and the Salzmann’s nodules are peeled away from Bowman’s layer,” Dr. Shafer says.

Dr. Shafer adds that “for a pterygium, excise the pterygium and remove it from the cornea. Use either a conjunctival autograft or an amniotic membrane graft to fill in the area over top of the sclera.”

Dr. Rubenstein is a consultant for Alcon. Dr. Shafer is a consultant for CorneaGen, which cuts CTAK tissue, and Glaukos. Dr. Jacobs and Dr. Blitzer have no related financial disclosures.

1. Noufal KH, Babu SP. Short-term visual outcome with sclerocorneal contact lens on irregular cornea. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2023;37:1:43-47.

2. Jacob S, Agarwal A, Awwad ST, et al. Customized corneal allogenic intrastromal ring segments (CAIRS) for keratoconus with decentered asymmetric cone. Indian J Ophthalmol 2023;71:12:3723-3729.

3. Greenstein SA, Yu AS, Gelles DJ, et al. Corneal tissue addition keratoplasty: New intrastromal inlay procedure for keratoconus using femtosecond laser-shaped preserved corneal tissue. J Cataract Refract Surg 2023;49:7:740-746.

4. Borderie VM, Georgeon C, Sandali O and Bouheraoua N. Long-term outcomes of deep anterior lamellar versus penetrating keratoplasty for keratoconus. Br J Ophthalmol 2023;108:1:10-16.

5. Salari F, Beikmarzehei A, Liu G, et al. Superficial keratectomy: A review of the literature. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:915284.

6. He X, Huang AS, Jeng BH. Optimizing the ocular surface prior to cataract surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2022;33:1:9-14.