Presentation

A 64-year-old man was referred to Wills Eye Ocular Oncology clinic for a pigmentary lesion on his left eye. He had seen an ophthalmologist three months prior, at which point the pigmented area had already been noted for approximately four months. The patient denied any vision changes, pain, redness or discharge.

|

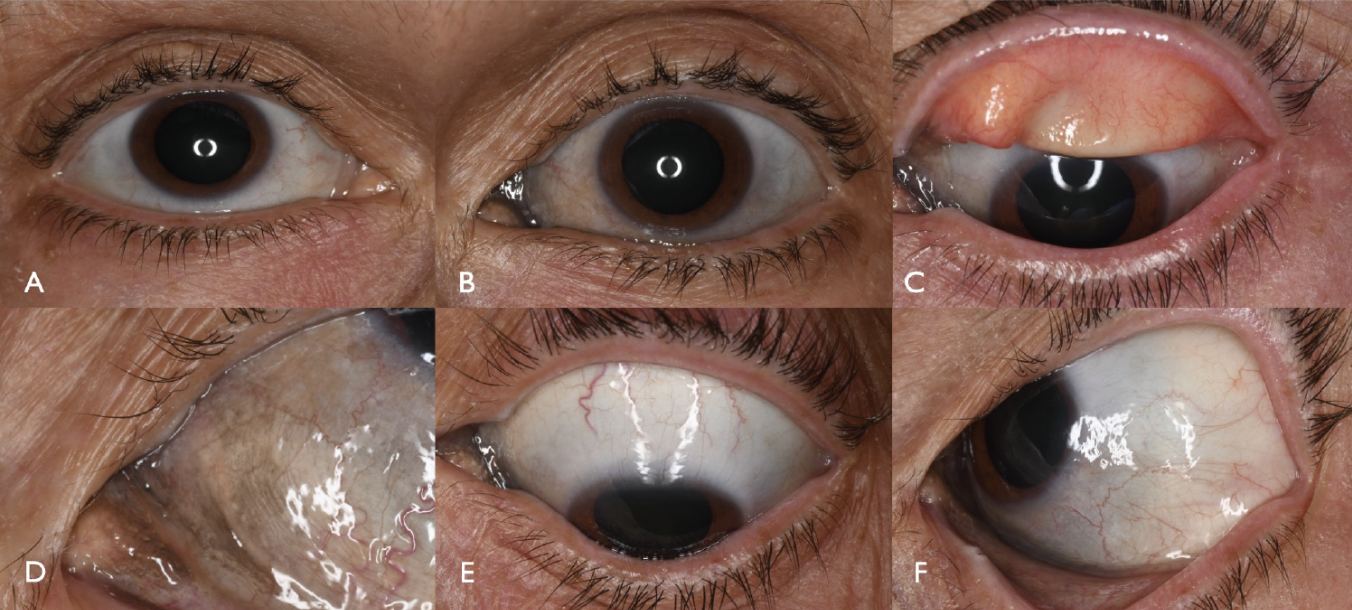

| Figure 1. External photograph of both eyes in primary gaze highlighting gray conjunctival inferonasal pigmentation on the left eye. |

History

The patient had an ocular history of central retinal vein occlusion in the left eye 10 years prior. He also had dry eyes, for which he took an over-the-counter eye drop. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia and benign prostatic hypertrophy, for which he took pravastatin and finasteride. He was a former smoker. Ocular family history included macular degeneration. Review of systems was unremarkable.

Examination

At presentation, corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left. The pupils were round and reactive in both eyes without an afferent pupillary defect in either eye. Intraocular pressures were 20 mmHg OD and 22 mmHg OS. Extraocular motility was full bilaterally.

|

| Figure 2. External photography at presentation of the right eye (A) and left eye (B) in primary gaze. Left upper eyelid eversion showing superior tarsus clear of pigmentation (C). The inferonasal conjunctiva demonstrated pigmentation (D), that was absent superiorly (E) and temporally (F). |

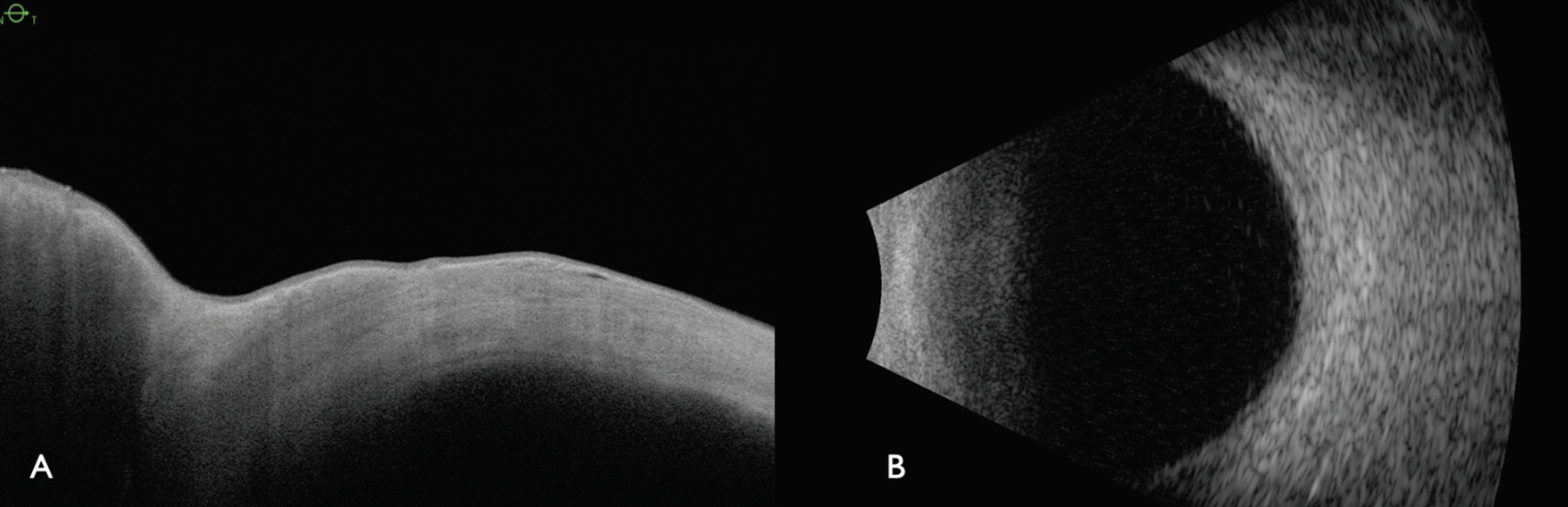

The anterior segment examination OD was unremarkable (Figures 1 and 2). The anterior segment examination OS revealed a diffuse (30 x 20 mm diameter) area of ill-defined gray pigmentation of the inferonasal bulbar conjunctiva, extending from the inferonasal limbus and involving the tarsal conjunctiva, plica semilunaris and caruncle (Figures 1 and 2). There was no skin, scleral, iris or choroidal involvement. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography of the conjunctiva OS was normal with no atypical thickening, hyperreflectivity or cystic changes. B-scan ultrasonography OS was unremarkable with no evidence of scleral or choroidal abnormalities (Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. (A) Anterior segment OCT and (B) B-scan ultrasonography of the left eye with normal findings. |

What’s your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

The differential diagnosis for a conjunctival pigmentary lesion includes benign and malignant melanocytic tumors such as complexion-associated melanosis (CAM), primary acquired melanosis (PAM), secondary acquired melanosis (SAM) and conjunctival non-melanin pigmentation from trauma, exposure, systemic diseases (ochronosis), mascara, tattoos or medications. Since the lesion was gray and unilateral, conjunctival deposition of an unidentified material was the suspected diagnosis.

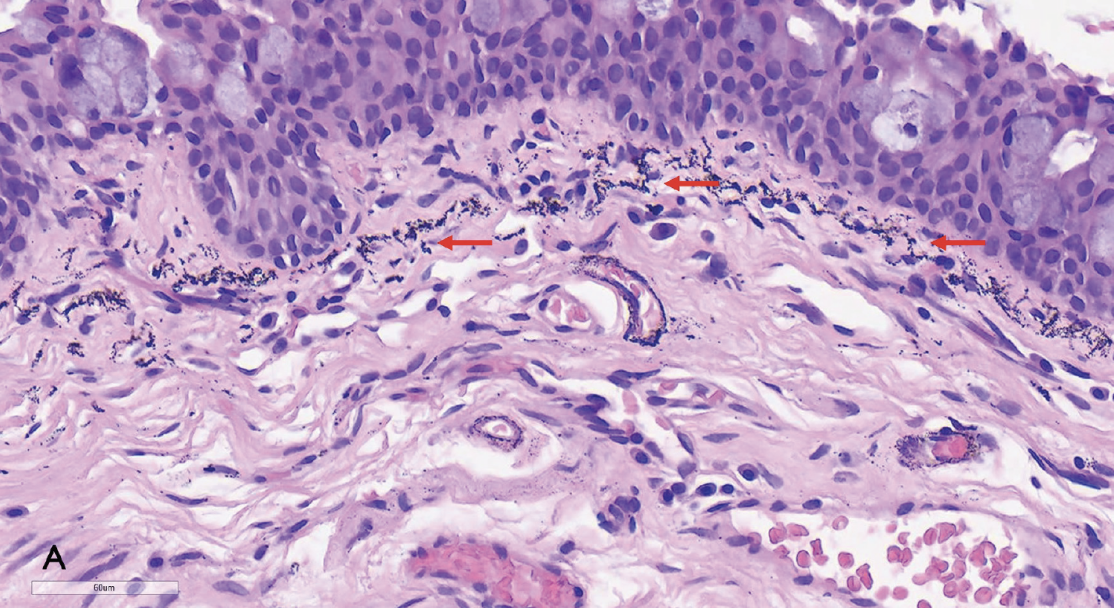

The patient underwent an incisional biopsy with cryotherapy to better understand the diagnosis. Histopathology demonstrated black, punctate, uniform size, non-birefringent deposits scattered deep to the epithelium between collagen fibrils in the stroma, and in a perivascular distribution (Figure 4). The deposits were primarily extracellular and associated with a mild chronic non-granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate. There was no evidence of malignancy. Further history revealed the patient used a medication, Nature’s Sunshine brand Silver Shield eye drops for nine years for dry-eye symptoms, three to four times a day, instilled directly into the eyes as advised by his naturopathy practitioner.

Our final diagnosis was conjunctival secondary acquired pigmentation (SAP) from Silver Shield eye drops. This medication was advised to be discontinued. The patient didn’t require additional treatment.

Discussion

|

| Figure 4. (A) Histopathologic specimen of the left eye from the nasal bulbar conjunctiva and plica semilunaris showing black, punctate nonbirefringent deposits (arrows) in the stroma, underlying the epithelium and focally in a perivascular distribution. |

Pigmented lesions of the conjunctiva include a variety of neoplastic and non-neoplastic conditions.1 Melanocytic neoplasms can present with few symptoms and include benign nevus, CAM, PAM and SAM, but it should be noted that serious life-threatening neoplasms can also occur in the conjunctiva, such as melanoma and pigmented squamous cell carcinoma.

SAM can result from a number of conditions including conjunctival trauma, inflammation, exposure from edema or exposure from elevation over pinguecula/pterygium/squamous cell carcinoma, by a mechanism of reactive melanosis of the conjunctival epithelium. In contrast, SAP can be caused by systemic disorders (such as Addison’s disease), ochronosis, or exposure to radiotherapy or chemicals. SAP can also be caused by deposition of medications (Argyrol, silver-dosed eye medications, oral minocycline/tetracycline), periocular makeup (mascara) or periocular/ocular tattoos.3-6 In contrast to SAM, SAP is pathologically characterized by deposition of pigment without melanosis, though clinically the presentation of SAM and SAP can be difficult to distinguish.1-4 An understanding of each of these conditions is important as each carries different implications on the ocular and systemic management.4,7

Notable to this case, SAP was from chronic conjunctival silver deposition and is known as conjunctival argyrosis, a condition that can be mistaken for CAM and PAM.7,8 The clinical symptoms of argyrosis relate to the gray discoloration of the conjunctiva that results from deposition of silver within the epithelium and later infiltration into the subepithelial layers.7-9 While this clinical manifestation may be cosmetically disfiguring, ocular argyrosis dosn’t cause visual disturbance.7-9

Historically, naturally occurring silver was used for various applications. In the late 1800s, silver nitrate was used as prophylaxis for neonatal ophthalmia to prevent the effects of ocular infections.10 Silver-containing drops are no longer used.9 Silver is still used for wound dressings (Nanocrystalline silver) and medical devices (bone cements, catheters, surgical sutures, cardiovascular prostheses and dental fillings) as a broad-spectrum anti-infection agent.9 Other common causes of ocular argyrosis include unintended exposure to silver compounds from inadequate eye protection in workplaces, such as with silver workers including polishers, engravers, and smelters; and workers in the photographic film and X-ray film manufacturing industry.7,8

In summary, this patient demonstrated conjunctival SAP from chronic exposure to silver eye drops. It’s worth noting that manifestations of SAP can masquerade as potentially a neoplastic process and it’s important to review the patient’s history, medication use, systemic conditions and exposures to uncover the proper etiology.

1. Bresler SC, Simon C, Shields CL, et al. Conjunctival pigmented lesions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2022;146:5:632-646.

2. Stulberg DL, Clark N, Tovey D. Common hyperpigmentation disorders in adults: Part I. Diagnostic approach, café au lait macules, diffuse hyperpigmentation, sun exposure, and phototoxic reactions. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:10:1955-60.

3. Liesegang TJ. Pigmented conjunctival and scleral lesions. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69:2:151.

4. Shields CL, Shields HA. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Surv of Ophthalmol 2004;49:1:3-24.

5. Gandhi V, Verma P, Naik G. Exogenous ochronosis after prolonged use of topical hydroquinone (2%) in a 50-year-old Indian female. Indian J Dermatol 2012;57:5:394-395.

6. Maloney SM, Williams BK, Shields CL. Long-term minocycline therapy with scleral pigmentation simulating melanocytosis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2018;136:11:e183088.

7. Tendler IM, Pulitzer MP, Roggli V et al. Ocular argyrosis mimicking conjunctival melanoma. Cornea 2017;36:6:747-748.

8. Zografos L, Uffer S, Chamot L. Unilateral conjunctival-corneal argyriosis simulating conjunctival melanoma. JAMA Ophthalmol 2003;121:10:1483-1487.

9. Landsdown ABG. A pharmacological and toxicological profile of silver as an antimicrobial agent in medical devices. Adv Pharmacol Sci 2010:910686. Epub 2010 Aug 24.

10. Moore DL, MacDonald NE, Canadian Paediatric Society. Preventing ophthalmia neonatorum. Paediatr Child Health 2015;20:2:93-96.