Presentation

A 71-year-old male was referred to the Wills Emergency Room with a concern for markedly elevated intraocular pressure in the right eye. The patient had been seen multiple times at outside optometry and ophthalmology practices for intermittent elevated IOP as high as 36 mmHg and 42 mmHg in his right eye. One month prior, he’d been treated for an unspecified unilateral keratitis with prednisolone acetate eye drops, and initially his elevated IOP was thought to be related to a steroid response. The patient also reported progressively worsening vision over this time, with his initial visual acuity at 20/40 OD one month prior then progressing to 20/100 OD over the month prior to presentation. He denied pain or pressure sensation. He also reported some swelling of the right upper and lower eyelids but was unsure how long this was present. He specifically denied eye redness, photophobia or diplopia.

|

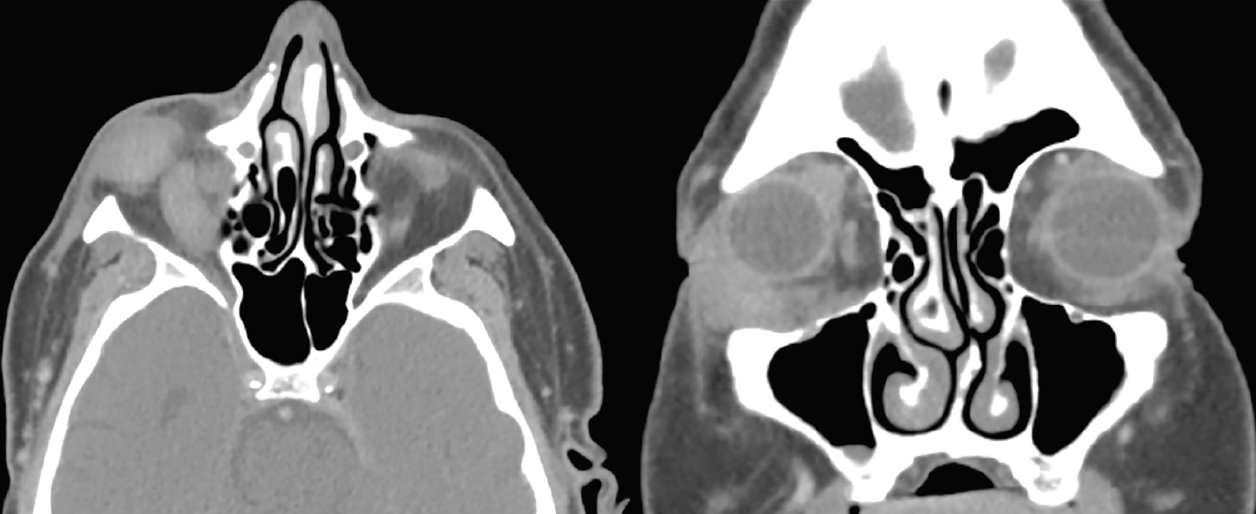

| Figure 1. Right orbital soft tissue mass and right extraocular muscle enlargement. CT scan of the orbits with contrast, axial and coronal sections. |

History

The patient had a medical history notable for coronary artery disease and prior myocardial infarction, deep venous thrombosis, aortic valve disease, peripheral vascular disease, hyperlipidemia, hypertension and atrial fibrillation on dual-antiplatelet therapy. His prior surgical history included coronary artery stenting and aortic valve replacement. He reported a prior smoking history of 15 pack years and occasional alcohol use. His family history included ovarian cancer in his mother and colon cancer in his father. The patient had no known prior ocular history.

Examination

At presentation the best-corrected visual acuity was 20/100 OD and 20/25 OS. His pupils were round and reactive. There was no evidence of a relative afferent pupillary defect OU, though he did report light desaturation in the right eye. Intraocular pressures were 12 mmHg OU. The patient was able to identify zero out of eight Ishihara color plates OD and eight out of eight OS.

External examination disclosed a palpable, non-tender mass in the lower right orbit which was nonmobile. There was marked proptosis of 4 mm and resistance to retropulsion OD. Extraocular motility was restricted in all directions of gaze in the right eye; there was only 10 percent inferoduction, 10 percent superoduction, 50 percent adduction, and 40 percent abduction. He had no visible skin lesions of the periorbital region or on the face.

Anterior segment examination demonstrated mild ptosis OD (MRD1 2 mm OD, 3.5 mm OS) and bilateral mild nuclear sclerosis cataracts, but was otherwise unremarkable. Posterior segment examination was unremarkable, including normal bilateral optic nerves without pallor, hyperemia or cupping.

What’s your diagnosis? What further work-up would you pursue? The diagnosis appears below.

Work-up, Diagnosis and Treatment

A CT scan of the orbits with contrast was obtained, which again highlighted right eye proptosis. A right inferolateral homogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass infiltrating between the insertions of the lateral and inferior recti measuring 1.5 cm x 2.3 cm x 1.1 cm was discovered. This study also disclosed an enlarged and centrally hypoattenuating right inferior rectus muscle, as well as enlarged superior, lateral, and medial recti and superior oblique muscles. There was crowding of the right orbital apex due to enlarged musculature. The left orbit was within normal limits. Representative sections from this CT scan are shown in figure 1.

Laboratory studies were also obtained at the initial visit. Labs were notable for an elevated sedimentation rate of 60, mildly elevated LDH of 282 and an elevated monoclonal IgM lambda of 0.11 g/dL. Thyroid function and thyroid immunoglobulin studies, complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, hemoglobin A1C, QuantiFERON gold, ACE, ANA, ANCA and IgG4 were all within normal limits.

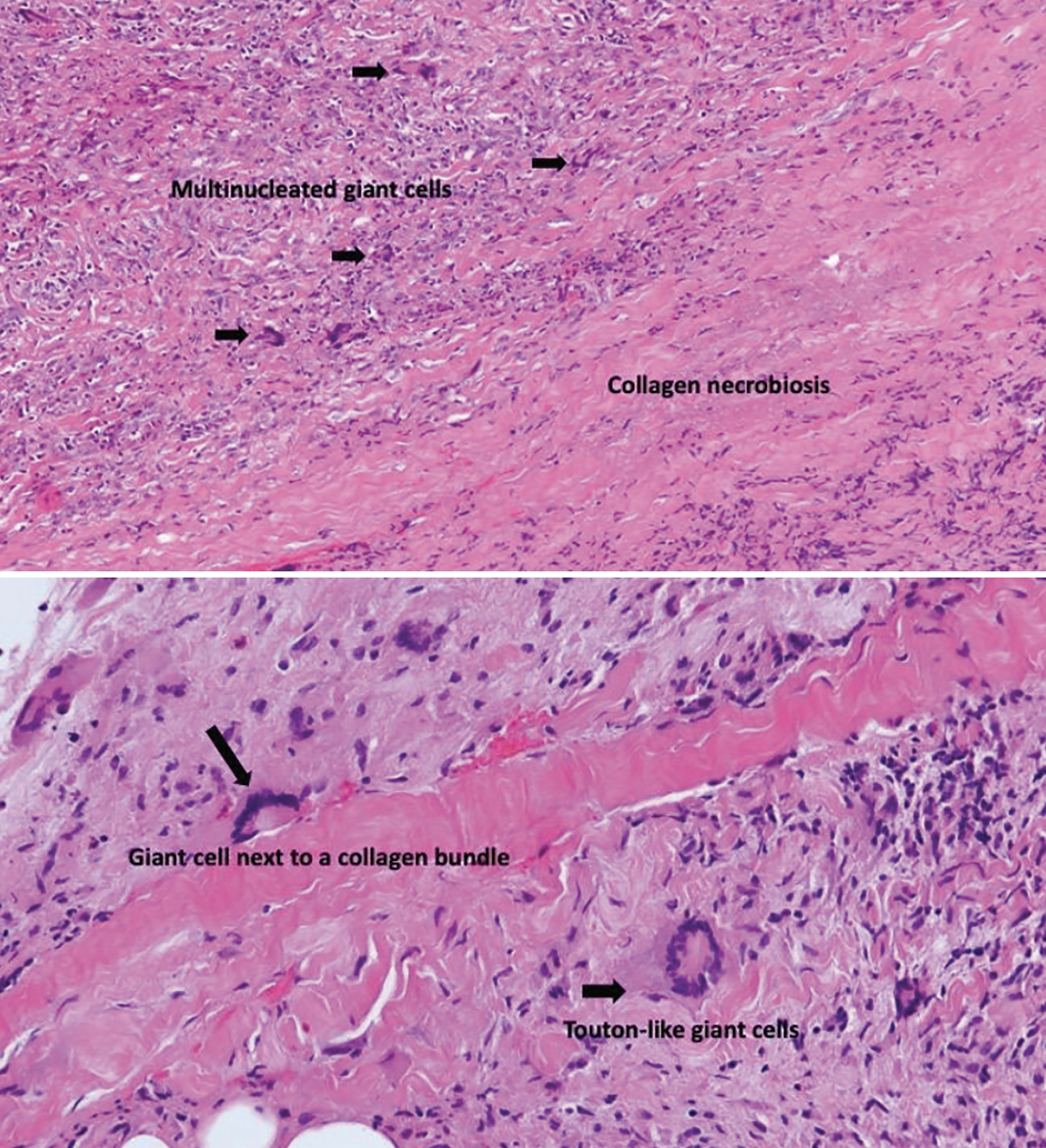

A biopsy was obtained of the mass in the right inferolateral orbit. Histopathology disclosed fibroadipose tissue with a mixed infiltrate largely composed of histiocytes, plasma cells, lymphocytes and rare lymphoid follicles in a background of intense fibrosis (Figure 2). Numerous multinucleated giant cells, mostly foreign body and Langerhans-type were present focally arranged around necrobiotic collagen. Immunohistochemical stains highlighted a mixed population of CD20+ B cells, CD3+ T cells, and CD138+ plasma cells, which were polytypic with a balanced kappa and lambda light chain expression. Although there was no xanthogranulomatous process seen, the combined pathologic and laboratory findings indicated possible necrobiotic xanthogranulomatous disease. The patient was referred to rheumatology and oncology given concern for Erdheim-Chester disease versus necrobiotic xanthogranuloma versus given the predominance of histiocytes and paraproteinemia.

Two months following initial referral, the patient underwent repeat laboratory workup. A significant drop in renal function was discovered, with creatinine of 2.18 from an initial 0.91, with associated hypernatremia. He has thus been referred to nephrology for further workup. He will undergo PET scan and MRI of the brain and orbits for further systemic assessment of his disease burden.

Discussion

|

| Figure 2. Histopathology of right orbit mass highlighting giant cells and collagen necrobiosis using hematoxylin and eosin staining. |

The term “orbital xanthogranulomatous disease” describes conditions in which there is orbital proliferation of non-Langerhans histiocytes. This encompasses four main disease categories: necrobiotic xanthogranuloma (NXG); adult-onset asthma with periocular xanthogranuloma, Erdheim-Chester disease; and adult-onset xanthogranuloma.1

This patient’s presentation is most concerning for

Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD). In this patient, tissue biopsy wasn’t ultimately diagnostic but was able to elucidate a final diagnosis within the spectrum of histiocytic disease. The pattern of histiocytosis, paraproteinemia, orbital infiltration into the posterior orbit and apex, history of valvular disease, and worsening renal function is consistent with a presumed diagnosis of ECD. This is a xanthogranulomatous disease in which there is a proliferation and accumulation of histiocytes in adults, often occurring in several areas of the body. Most often ECD is seen in the long bones, but has been seen in the periorbital skin and the orbit.2,3 Orbital disease typically presents with exophthalmos, extraocular movement abnormalities, and/or vision loss related to infiltration surrounding and within the extraocular muscles.4 Patients may also present with eyelid xanthelasma, chemosis and sequela of compressive infiltration of the posterior orbit including compressive optic neuropathy, as seen in the patient described in this case report.5 ECD typically affects the posterior orbit and can infiltrate further posterior into the cavernous sinus. ECD can also affect the central nervous system, notably with infiltration of the pituitary gland and hypothalamus.5

Other manifestations of ECD include those in the cardiovascular system. It’s estimated that roughly 17 percent of patients with ECD develop symptomatic valvular disease. This patient had recently undergone aortic valve replacement for aortic valvular disease, which may have been related to his presentation described above.6 Patients with ECD can also develop renal dysfunction and ultimately even renal failure, similar to our patient.3 It’s important to note that this patient has been referred to nephrology for characterization of renal failure, but his differential for renal failure is highly concerning for ECD-related infiltrative disease versus deposition from known paraproteinemia.

Tissue biopsy is typically required to make the diagnosis of ECD, most often in conjunction with imaging of affected sites and to rule out other infiltration. Laboratory studies are recommended at diagnosis to assess for endocrinopathies, blood count abnormalities, systemic immunologic/inflammatory conditions, and renal or hepatic disease.4 Treatment of ECD involves observation for asymptomatic patients, or systemic therapy for symptomatic patients depending on system involvement. Therapies for ECD can involve BRAF inhibitors, systemic cytotoxic therapies, and immunomodulatory medications, including glucocorticoids. Surgery is typically not involved in treatment.2

Another consideration for this patient’s diagnosis is necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. NXG specifically involves proliferation of histiocytes with associated lymphocytes, giant cells and varying degrees of fibrosis as well as necrobiosis, which is the degeneration of collagen.1 The pathogenesis of this condition isn’t well-understood, but is thought to be caused by reaction and proliferation of macrophages in the tissue.1 NXG proliferation of macrophages has been postulated to be associated with viral infection, immunoglobulin deposition, and paraproteinemia, among other potential causes.7

NXG often presents with cutaneous lesions that are typically firm and yellow-orange in color. These lesions can be seen anywhere on the body, but most commonly are found in the periorbital region.7 The most commonly reported ocular findings include these periorbital skin findings, as well as proptosis, ptosis, palpable anterior orbit lesions and restricted eye movements.8 The patient in this case study presented with an anterior orbital lesion and eye muscle enlargement but no skin findings. Radiographic studies have shown extraocular muscle involvement in this disease process. Laboratory studies most commonly disclose elevated sedimentation rate and IgG kappa monoclonal gammopathy, similar to this patient.9

Data is mixed regarding specific diagnosis of systemic proliferative disease in light of the frequency of associated monoclonal gammopathy. Patients diagnosed with NXG have been reported in association with multiple myeloma, plasmacytosis and lymphoproliferative disorders.6 This disease entity should be considered in this patient given his elevated inflammatory markers and paraproteinemia.

NXG tends to be a progressive and chronic condition.8 Its treatment includes multiple modalities, all with inconsistent and mixed results when reviewing the literature. Alkylating agents are the most commonly reported treatment, with varied responses to treatment reported, either alone or in conjunction with systemic corticosteroids.8,9,10 Other treatment modalities involve both intralesional and systemic corticosteroids, again with mixed reported results in the literature.11 Excision has been shown to have a possibly favorable response,10 though previous literature reviews have shown recurrence with excision.4,9 Interestingly, it’s been shown that the NXG lesions often don’t resolve in patients with monoclonal gammopathy even after the systemic disease has been adequately treated.12

In conclusion, this patient presented with one month of intermittent intraocular pressure elevation and progressive vision loss in the right eye. On examination, a right orbital mass was discovered as well as proptosis limitation of extraocular motility of the right eye. Further investigation including imaging, serologic studies and incisional biopsy disclosed paraproteinemia as well as histiocyte proliferation and necrobiosis of collagen consistent with possible Erdheim-Chester disease versus necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. This infiltration of the orbit and extraocular muscles has precipitated the above orbital signs and optic neuropathy. The patient is currently being referred to rheumatology and oncology for further assessment for possible treatment, which may include systemic immunomodulatory versus cytotoxic medication.

1. Kerstetter J, Wang J. Adult orbital xanthogranulomatous disease: A review with emphasis on etiology, systemic associations, diagnostic tools, and treatment. Dermatologic Clinics 2015;33:3:457-463.

2. Shamburek RD. Erdheim-Chester Disease. In: The NORD Guide to Rare Disorders, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2003:441.

3. Cavalli G, Guglielmi B, Berti A, et al. The multifaceted clinical presentations and manifestations of Erdheim-Chester disease: Comprehensive review of the literature and of 10 new cases. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1,691.

4. Goyal G et al. Erdheim-Chester disease: Consensus recommendations for evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment in the molecular era. Blood 2020;135:22:1929-1945.

5. Merritt H et al. Erdheim-Chester disease with orbital involvement: Case report and ophthalmic literature review. Orbit 2016;35:4:221-226.

6. Costa IBSDS et al. Cardiovascular manifestations of Erdheim-Chester’s Disease: A case series. Arq Bras Cardiol 2018;111:6:852-855.

7. Spicknall KE, Mehregan DA. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. International Journal of Dermatology 2009;48:1:1-10.

8. Ugurlu S, Bartley GB, Gibson LE. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: Long-term outcome of ocular and systemic involvement. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;129:651–657.

9. Mehregan DA, Winkelmann RK. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Arch Dermatol 1992;128:94–100.

10. Cornblath WT, Dotan SA, Trobe JD, Headington JT. Varied clinical spectrum of necrobiotic xanthogranuloma. Ophthalmology 1992;99:1:103-107.

11. Plotnick H, Taniguchi Y, Hashimoto K, et al. Periorbital necrobiotic xanthogranuloma and stage I multiple myeloma. Ultrastructure and response to pulsed dexamethasone documented by magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;25:373–377.

12. Flann S, Wain EM, Halpern S, et al. Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma with paraproteinaemia. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31:248–251.