When you’re managing glaucoma, the initial patient encounter and glaucoma evaluation is always the most important. It’s when diagnoses are made, treatment goals are set and a treatment plan is formulated. These are critical and time-sensitive.

Getting these things right during the initial visit is crucial, because these decisions set the direction of our disease management, possibly for years to come. Once we start on our treatment path, we often don’t question certain fundamentals. For example, misclassifying the glaucoma as open-angle when it’s actually closed-angle can be devastating, even for astute clinicians trying to do their best for the patient. To put it another way, a first-visit error (for lack of a better word) can really live on.

Here, I’d like to offer some thoughts about the things we need to address during a patient’s first visit, to get our relationship with the patient off to a good start, address the patient’s concerns and expectations, and ensure an accurate diagnosis and viable treatment plan. Many of my patients are referred to me by other doctors, and being in that position adds additional factors to consider during the first patient visit, so that’s the primary focus of this article. However, I believe many of my comments will apply to any doctor seeing a glaucoma patient for the first time.

Before the Visit

As much as possible, don’t see a referred patient until you’ve received the patient’s records. It’s perfectly reasonable to demand that the patient’s records be delivered to your office prior to scheduling the visit, especially if you know it’s an individual with a significant history. You need to understand how long the patient has had the disease, how quickly it’s progressing, what the pressure was at the first visit, and which medications, lasers and surgical treatments the patient has had.

Unfortunately, many patients don’t understand what it means to transfer records. They assume that doctors are automatically doing this all the time, so they expect me to have their records when they show up; they don’t realize that I can’t get their records without their signature. For that reason we explain this to new patients and tell them that we won’t schedule their visit until we receive the records. (My favorite approach is to ask the patient to physically pick up their records from the other doctor and bring them to my office.)

One reason that having these records is so important is that patients can be very unreliable when it comes to their recollection of previous treatments. For example, I recently offered an SLT treatment to a patient, but she was convinced she’d just had this treatment at a different hospital. I was able to determine that that laser procedure she’d had was an iridotomy. If I hadn’t been able to confirm that, I would have had to eliminate a procedure that could’ve helped the patient.

|

Another reason you need to have the records is that brimonidine allergy happens in about 20 percent of patients. In my experience, about 90 percent of the people who have a brimonidine allergy forget the name “brimonidine.” If you don’t have the records, you may give them the drop they’re allergic to, causing a red, inflamed, itchy eye. This creates an unnecessary problem for both you and the patient.

All these aspects of the history—and others—are really important. Having said that, we all see patients who’ve been treated previously but don’t have their records. I’m willing to proceed if the records are missing for a good reason, such as the previous treatment taking place in a foreign country. But it’s always worth making the effort to get the records. Having the records makes everything a lot easier.

Managing Expectations

As we all know, unrealistic expectations can lead to trouble down the line. The first visit is the place to begin managing this potential problem. A few helpful strategies:

• Determine the level and nature of the patient’s anxieties, and address them. It’s crucial to find out what the patient is thinking and feeling about his or her condition. Patients can bring a limitless amount of anxiety to their visit—and there may be no correlation between the patient’s personal level of concern and their disease severity. Some patients will come in who have no disease but are very concerned; some will have serious disease but not be concerned at all. Regardless of which scenario you face, knowing what the patient is thinking and feeling is critical so you can address their concerns, lower their fear level and manage their expectations.

• Tell the patient that your goal is to avoid surgery, if possible. To me, the most important question you can answer for a glaucoma patient is whether he or she can be managed medically or will require surgery. With that in mind, I tell my new patients that my primary goal is to make sure they don’t go blind, and my second goal is to help them avoid surgery, if possible. Patients usually understand the reason for these goals and agree with them.

• Set ground rules for the role of the referring doctor. If your patient was referred by another doctor, that doctor becomes “the third person in the room”—and the referring doctor’s goals can complicate the initial visit. Sometimes referring doctors are asking you to take over the glaucoma care; sometimes they want you to manage the patient’s glaucoma while they continue caring for the patient’s other eye problems; and sometimes they have a specific procedure such as SLT that they’d like you to do. It’s important to determine what the referring doctor’s goals are during the first visit. (Of course, in some cases you may have to overrule those goals.)

If the referring doctor wants me to do a procedure, I’ll usually do it—as long as I believe it’s reasonable. After all, that doctor knows the patient better than I do. They’ve usually talked to the patient about the procedure, and the patient was amenable or they wouldn’t be coming to see me. I don’t think the glaucoma specialist always needs to question the referring doctor’s requests. Once the treatment is done, I usually send the patient back to their doctor and say, “I’m here if you need me, but right now I think your doctor is doing a great job. You should continue seeing him or her for a while.”

I believe one of the most important ground rules to establish in a referral situation is that only one glaucoma specialist should manage the disease on an ongoing basis. If that person is likely to be me, I invite patients to get a second opinion about any recommendation I make, if they wish; but after the second opinion, they have to either switch to the other doctor or stay with me. I don’t do “two cooks in the kitchen.” It’s not uncommon for some patients to want that, but there are too many different ways to treat glaucoma to have more than one doctor calling the shots. So for me, the rule is: Every patient gets one glaucoma specialist—if they want one—but never more than one.

• Be careful about how you provide hope. It’s really important to give patients hope, but we have to be very careful to provide hope in the right way. Many patients who’ve lost vision from glaucoma are hoping to have it restored. They want the impossible.

It’s important to explain this to these patients, in the nicest possible way, and to remind them again from time to time. A patient who wants to regain vision probably won’t accept that the lost vision isn’t coming back if you only say it once. The desire to regain vision is so powerful that you’ll often need to remind them: Once you lose vision to glaucoma you can’t get it back.

|

The first visit is the place to start clarifying this. Begin with a hopeful and caring tone, saying, “We can treat you and take care of you and make sure you keep the good vision that you have. If we work together we can hopefully stabilize your disease and prevent future blindness.”

It’s also common for these patients to ask about new possibilities such as treatments using stem cells. You have to be very careful how you answer those questions. If you say something like, “There are doctors working on stem cell treatments for glaucoma and they look promising,” most patients will take that to mean that at their three-month follow-up you’ll have a stem cell treatment. They don’t understand how slowly progress is made in these areas. So, I tell them, “I don’t think it’s likely that we’ll have that type of treatment in our lifetime, but we can hope.” (They’ll still keep asking how the research is going.) So we have to choose our words carefully and be prepared to live with whatever we’ve said.

Risk Factor Assessment

This is a relatively straightforward part of the initial exam. The goal is to identify high-risk patients. Factors to consider include:

• Consider the patient’s age. I think of age as the double-edged sword of risk factors, because it does increase the likelihood of glaucoma getting worse, but it also decreases the amount of time the patient will have to live with the disease. So in some cases being older will increase the seriousness of the problem; in others, such as a patient with a mild case of glaucoma in their late 80s, the disease might not even need treatment.

• Factor in central corneal thickness and hysteresis. In recent years, corneal hysteresis (a measurement of the cornea’s ability to manage stress) has been validated as a risk factor for both the development and progression of glaucoma. Most of my offices have an instrument to measure this, but I understand why a lot of people don’t have access to the technology. If you can measure hysteresis, that’s great. If not, be sure to consider the central corneal thickness as a risk factor.

• Don’t assume patients will be aware of their family history. In my experience, most patients don’t know for sure whether a family member has had glaucoma. Some will recall that a family member had eye surgery, but won’t know whether it was cataract surgery or glaucoma surgery. For that reason I find it more helpful to simply ask if any family went blind over a period of years.

• If one eye has lost vision, find out why. About every fourth glaucoma patient I see has already lost vision in one eye. (Many people lose vision in one eye before they even go to a doctor.) If this is the case, it’s important to confirm how vision was lost in the other eye. For example, if vision loss was caused by a previous glaucoma surgery, you may not want to do that surgery again. The patient’s records may be crucial to answering this question.

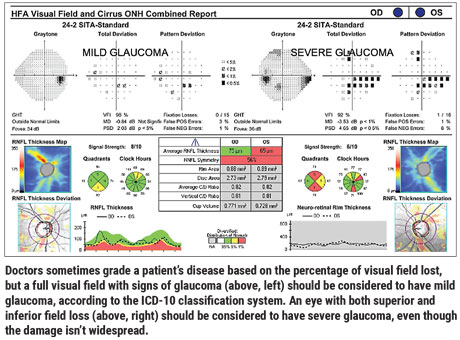

• Don’t under-stage the patient’s disease. In my experience, doctors tend to grade a patient’s disease based on the percentage of the field that’s lost, even if there’s damage in both the superior and inferior regions. They’ll say, “He’s still got half his field remaining, so it’s not that bad.” But glaucoma doesn’t really work that way. The risk of an eye going blind from glaucoma is significantly higher if the eye has both superior and inferior field loss.

For example, consider the eyes shown on page 61. Many doctors would grade the field on the left as preperimetric glaucoma, or even a glaucoma suspect. In fact, according to the ICD-10 classification system, that’s mild glaucoma. Similarly, many doctors would grade the field on the right as early or moderate glaucoma, when in fact it’s severe glaucoma according to the ICD-10 classification.

To put it another way, if a patient shows signs of disease but still has a full visual field, that’s mild glaucoma. A field with just a few points of loss is severe glaucoma, especially when you find damage in both the superior and inferior regions. That eye is at high risk of eventually going blind.

Needless to say, we do our patients a serious disservice if we under-stage their disease.

• Be careful when establishing the speed of progression. When we get the patient’s old records we can start to piece this together and determine whether the patient is stable or deteriorating. In many cases, a patient is referred because the other doctor thought the patient was rapidly progressing, when in reality, the patient had one bad test. Simply repeating the test may be enough to indicate that the eye is actually stable. So, if the evidence appears to suggest the patient needs surgery, double check to make sure that conclusion is valid. Never base a decision to do surgery on the results of one test. (Of course, there may be exceptions. If the difference between an old test and your new test result is sufficiently extreme, and the other evidence you have supports rapid progression, you may be justified in taking the patient to surgery.)

• Factor in how many drops the patient is unable to use. That’s important because every eye drop allergy or intolerance dramatically increases the risk of the patient needing surgery.

The Physical Exam

There are several things you want to be careful not to miss during your first patient exam. These include:

• Endothelial disease. This is easy to overlook. Always take the time to check carefully for endothelial guttae, or prior surgeries such as tube shunts touching the corneal endothelium.

• Brimonidine allergy. Sometimes when patients are referred to our office they’re already using multiple drops. In that case, if an eye looks red and inflamed and the pressure’s out of control, a brimonidine allergy could very well be the problem. It’s a very common reason for patients to seek out a second opinion, because the patient can tell something is wrong, even if the doctor doesn’t see it.

So, if you’re the doctor giving the second opinion, and the eye looks very toxic and red or inflamed, stopping brimonidine is often a successful strategy.

• Pseudoexfoliation. This is one of those conditions that gradually worsens over time, sneaking up on the doctor and patient. In the beginning it can be present in extremely subtle form, so if you’re on the lookout you may spot early signs of pseudoexfoliation that many doctors would miss. Examining the mid-peripheral anterior lens capsule in the dilated eye for early exfoliation material or pigment can be the most sensitive way to detect the disease.

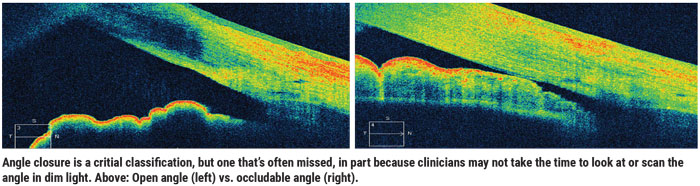

• An occludable angle. Angle closure is a critical classification, yet it’s often missed. That’s true for several reasons. One is that doctors often look at the angle in a brightly lit room, which can cause the angle to open.

Ideally, you should look at the angle using gonioscopy under dim illumination. In today’s digital world, that means turning off the iPad, having the patient put their phone away, turning off the computer monitor and shutting the doors. (If you’re not in the habit of doing gonioscopy in the dark, try it for a month. You’ll be amazed how many additional cases of angle closure you detect.) People spend at least a third of their lives sleeping in the dark, and if someone has a narrow angle, you can bet their angle is even narrower during that time.

Another approach to monitoring the angle is anterior segment optical coherence tomography. It’s a good screening tool, but it’s subject to the same caveat; doctors often take the scan in a brightly lit room. Taking it in a very dark room is key to catching angle closure.

A few pearls:

• If you’re checking for angle closure in a darkened room, be patient. If I’m using gonioscopy to check for a narrow angle in dim light conditions, and I get the sense that the patient’s angle is closing, I’ll wait a little longer—as long as five minutes. This will often result in the angle closing to a dangerous degree. I certainly don’t do that with every patient; if I turn off the lights and the angle remains widely open, I can tell it’s not going to close. But if the angle is starting to close in the dark, it’s worth it to wait and see just how closed it will get.

• If you have anterior segment OCT capability, consider scanning every patient to check for angle closure. Doing so only takes about 20 seconds of technician time. This is routine in our practices, and we almost never bill for it. The result does sometimes catch me by surprise; an angle I didn’t think was narrow looks quite narrow on the OCT scan.

• Remember that angle closure can change over time. It’s important to check the angle periodically because angle closure can progress. An angle that looked open two years ago may now be narrow. It’s easy to classify the patient at the initial exam and then stop looking, but that can backfire. I think it’s important to reassess the angles at least once a year, and any time the patient’s characteristics or IOP are changing. If you’re consistent about this, you can save many people’s vision.

Challenging Prior Conclusions

I’ve found it interesting how many times a note in the chart from a referring doctor (or a statement coming from the patient) turns out to be leading us in the wrong direction. For example, you may be told that a patient can’t take one of the commonly prescribed drops, or that a drop was tried and produced little effect. I’m all for honoring these conclusions if I have all the options in the world still open to me, but the reality is that glaucoma patients go blind when they run out of options—medical, laser and ultimately surgery—so you don’t want to eliminate a treatment option without checking to be sure it’s really off the table. For that reason (and based on my first-hand experience) I always assume that these conclusions could be mistaken.

I refer to some of these assumptions as “pseudo-contraindications.” For example, a patient may come in quite sure that he or she can’t take such-and-such a medication. In many cases, this conclusion was the result of a miscommunication. I’ve experienced this with my own family. My aunt has glaucoma; she was placed on a medication while being seen by another doctor, but her pressure didn’t come down much. The doctor said, “This drop isn’t for you.” Then, it was placed on the list of drops she couldn’t use in the future—not an appropriate conclusion!

I’ve encountered pseudo-contraindications relating to several different drug classes:

— Beta blockers. Sometimes I’ve seen a note in a patient record saying “The patient can’t take a beta blocker.” If you ask the patient why, she may say, “My doctor prescribed me an asthma inhaler.” Upon further investigation, the patient doesn’t have asthma but was prescribed an asthma inhaler for bronchitis several years ago. You may end up avoiding prescribing a beta blocker that could have helped the patient because of a misunderstanding. That’s not uncommon.

— Prostaglandin analogues. Some patients have been told to avoid prostaglandin analogues because the label states that PGAs can cause uveitis. In my experience uveitis caused by a PGA is rare and almost unheard of. It’s based on a case report from shortly after the PGAs were discovered, and my guess is that it was a patient who just happened to have uveitis that wasn’t caused by the PGA. But because prostaglandins are involved in inflammation in the prostate and other areas of the body, the concept stuck.

Unfortunately, the result has been that some patients who are going blind with mild uveitis and severe glaucoma often don’t even get tried on a PGA for fear of this contraindication mentioned in the labeling. This has eliminated the possibility of using the single most effective therapy we have to help many desperate patients, for no good reason.

— CAIs. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are technically in the sulfa class, but they’re not contraindicated in patients who’ve had a sulfa antibiotic allergy. There’s no cross-reactivity between those two medications; they both just happen to have an atom of sulphur in their chemical formulas. In fact, in the military soldiers with a sulfa allergy are routinely given an oral CAI—Diamox—without problems.

A 2013 study by M. Bruce Shields, MD, and colleagues evaluated more than 1,000 glaucoma patients; it found that while sulfa-allergic patients may have more allergies overall, the CAI class was not a particular problem.1 Nevertheless, you’ll still see a lot of pharmacists disallowing it to patients, some of whom might lose their vision without another drop.

For these reasons I don’t assume that patients who say they can’t use a drug are correct, if the reasoning sounds questionable to me. I rechallenge patients who say that a medicine didn’t work for them, if they only tried it once briefly. I also check to see if a feared drug interaction is legitimate. At the least, you want to properly weigh the risk of the allergy or uveitis against what in most cases is a very serious risk of going blind from glaucoma.

If you do this appropriately, you may open up treatment options that will help to save the patient’s sight.

Overall Visit Strategies

Pearls to keep in mind:

• Don’t be afraid to treat early glaucoma aggressively. Early glaucoma grows up to be severe glaucoma, and the more aggressively we treat early glaucoma, the better we do at keeping our patients out of trouble. The reality is that you can’t always tell which early glaucoma patients are going to go on to need surgery. As a result, it’s always a good idea to err on the side of more treatment, not less.

• Look for “low-hanging fruit.” One of the best things you can do for a new patient is look for things you can do right away that may give them some relief. I think of these treatments as my “fastballs.” These include:

— If the eye is irritated, especially with follicular conjunctivitis, try eliminating brimonidine from the patient’s regimen. As noted earlier, brimonidine allergy is common and often missed. If the drug is causing some of the patient’s suffering, eliminating it will bring the patient some quick relief.

— Make sure the patient has really tried all of the main medications. Any exclusions may have been the result of an inadequate trial or a false assumption, as noted above.

— Make sure the patient has had SLT. I’ve had many patients referred to me for surgery for whom I think SLT may handle the problem.

— Try pilocarpine. Pilocarpine is my “get out of jail free” card, for people who are really looking to avoid surgery. It’s almost never been tried when a patient is referred to me. You might argue that it’s an old treatment; it doesn’t work that well, and it has pretty bad tolerability. That’s true. But it gives me one more chance to show some due diligence before I take the patient to the OR.

• Before moving to surgery, exhaust your other options. When possible, proceed slowly. I do schedule some patients for surgery the first time I see them, but in most cases I try to develop a little rapport and trust with the patient first, and make sure we’re comfortable with each other’s styles. There’s a long waiting time to get an appointment to see me, so I don’t like to bring people to my office unless I think they’re going to be comfortable not rushing. Once I know the patient is willing and able to proceed slowly, I’m happy to have one more visit, one more pressure check, one more trial of a new medication, before resorting to surgery. That can go a long way to show patients that you’re willing to work for them and trying to avoid the need for surgery.

|

• If you need to make a surgical plan at the first visit, clarify expectations. If a new patient has advanced glaucoma or is progressing rapidly, you may need to make a surgical plan right away. However, because the patient is new, you won’t have a well-established relationship with the individual. For that reason:

— Make sure the patient understands the goals and risks of the glaucoma procedures you’re considering. This is essential to avoid unrealistic expectations and postop distress.

— Remember to reinforce that you can’t bring back vision that’s already lost. I often say, “Your eye doesn’t have the vision you’d like it to have, but it still has useful vision, and I’d like to keep that vision for you with this surgery.” As noted earlier, it takes some repeating to drive home the point that we can’t bring back lost vision.

— Remember that the referring physician may have unrealistic expectations as well. Interestingly, this is not uncommon. You’d think that because this person is an ophthalmologist or optometrist and has a lot of experience his or her expectations would be realistic, but not everyone understands glaucoma as well as we might hope. I was sent a patient recently from a well-known ophthalmologist, and the referring physician was shocked that I couldn’t bring back the vision lost to glaucoma.

The Main Points

To sum up, when a patient is referred to you, keep several things in mind during your first visit:

- If possible, don’t schedule the visit until you have the patient’s records in-house.

- Do your best to give the patient a realistic amount of hope—but be careful about the words you choose.

- Focus on the most important parts of the history.

- Don’t omit critical exam features such as checking for an occludable angle.

- Look for some low-hanging fruit that you can address to reduce the patient’s suffering.

- If surgery is needed, it’s OK to be decisive. However, be clear about what the patient can and should expect.

One final thought: As important as the first visit is, it’s also crucial to avoid simply staying the course for years after, assuming that the conclusions you drew during the first meeting still apply. Our glaucoma patients’ diagnoses and treatment goals can change throughout their lives—probably not every visit, but maybe every few years. That’s not to say that we should approach every visit the same as the initial encounter, but we should re-examine some key factors such as angle closure periodically. In short, remain vigilant for changes over time. REVIEW

Dr. Radcliffe is a clinical associate professor at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, and practices at the New York Eye Surgery Center. He reports financial ties to Reichert, Allergan, Alcon, Novartis, Lumenis, Ellex, Aerie and Bausch+Lomb.

1. Guedes GB, Karan A, Mayer HR, Shields MB. Evaluation of adverse events in self-reported sulfa-allergic patients using topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 2013;29:5:456-61.