On a typical day in the OR, cataract surgeons are most likely going to deal with traditional presentations with no hiccups. However, every so often they need to be prepared for rare cataracts and their inherent challenges, whether it’s a hyper-mature Morgagnian, traumatic or even the visually striking Christmas tree cataracts.

“I perform approximately 6,000 cataract surgeries a year, so just by sheer probability it’s common for me to see all of these presentations,” says Douglas K. Grayson, MD, who is a cataract and glaucoma specialist at Omni Eye Services in New Jersey, as well as an attending surgeon at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary. “Even the hyper-mature cataracts—you’d be surprised that patients can walk around with good vision in one eye and not realize an issue in the second eye until something obstructs it.”

Here, we offer helpful reminders and tips to successfully navigate a few of these unique cataracts.

Morgagnian

Morgagnian cataracts are hyper-mature cataracts, where the cortex of the lens is fully liquefied, and the nucleus is essentially floating in this liquid pool of cortex. According to Amanda C. Maltry, MD, who is a general ophthalmologist and ophthalmology pathologist, as well as an associate professor at the University of Minnesota, Morgagnian cataracts are often called “Sunset” cataracts.

“When the patient is seated upright at the slit lamp, the nucleus sinks to the bottom, resembling the setting sun,” says Dr. Maltry. “One significant concern in these cases is that the liquefied cortical proteins can leak through the lens capsule. This leakage can lead to protein accumulation in the anterior chamber, where macrophages may attempt to clear it, potentially clogging the trabecular meshwork and causing an increase in intraocular pressure, or phacolytic glaucoma. Therefore, the main reasons for performing cataract surgery in these cases are to prevent secondary glaucoma and to clear the visual axis by removing the opacity.”

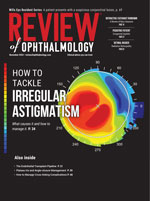

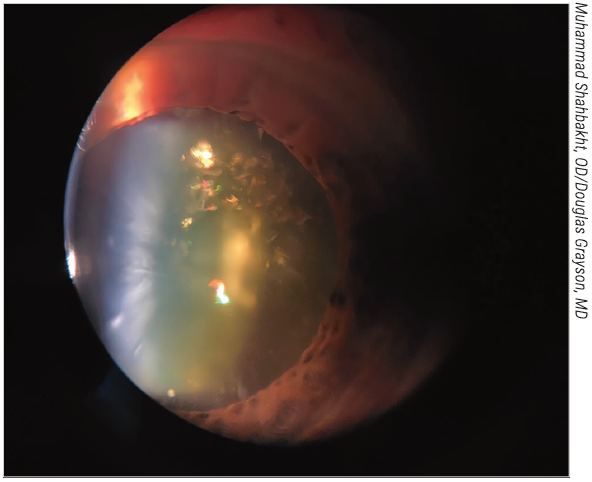

|

|

In cases of hyper-mature Morgagnian cataracts, the cortex has liquefied and the dense nucleus has sunk to the bottom of the capsular bag. This can make the capsulorhexis challenging and surgeons say the pressure inside the capsule could increase the risk of radialization, resulting in the Argentinian flag sign. |

Attempting the capsulorhexis is one of the most challenging surgical aspects for Morgagnian cataracts, says Dr. Maltry. “Due to the liquefied cortex, the lens capsule can be under pressure,” she says. “This pressure increases the likelihood that the initial puncture during capsulorhexis will radialize or result in an Argentinian flag sign. That’s probably the thing that always gets my blood pressure up a little bit at the start of these cases.”

Some may opt for making an initial incision with a blade, says Dr. Grayson. “Doing a capsulotomy in a floppy anterior capsule can be quite challenging,” he says. “In these cases you may need to use one of the blades, either the paracentesis blade or the keratome, to initially incise the anterior capsule for the capsulotomy.”

On the other hand, Dr. Maltry says, based on her experience, a well-filled anterior chamber is effective and negates the need to aspirate. “I ensure that the anterior chamber is fully filled with viscoelastic to flatten the anterior capsule,” she says. “You could also consider a shell technique where you start with a dispersive viscoelastic and then inject a heavier weight cohesive viscoelastic, such as Healon 5.”

Dr. Grayson prefers Viscoat. “It’s advisable to use a dispersive viscoelastic,” he says. “Sometimes, aspirating out the liquefied cortex can enhance visualization. Ultimately, success in these procedures hinges on visualization and control, which can be achieved using a combination of trypan blue, aspiration of some cortex and viscoelastic.”

Both surgeons emphasize the value of trypan blue stain. “Using trypan blue to stain the capsule is essential, as the lens is completely opaque and there will be no red reflex,” says Dr. Maltry.

Once the capsulorhexis is complete, cataract surgeons must evaluate how to proceed with removing the nucleus. “Since the cortex is now liquid, that will all aspirate out quickly, leaving the nucleus loose yet dense within the capsule,” says Dr. Maltry. “Gaining purchase on the nucleus with the phaco tip can be difficult. One strategy is to envelop the nucleus with viscoelastic by injecting it behind and in front of the lens, creating a sandwich effect to trap the nuclear fragment. This technique helps reduce the required phaco energy and protect the corneal endothelium. I find that using a phaco chop technique is effective, as grooving the lens is difficult due to its instability and density. In recent years, the MiLoop has also become a useful tool in such situations, though I don’t use it frequently.”

Dr. Grayson says he hasn’t personally used the MiLoop, although he knows of some surgeons who’ve had success with it. “Whether it adds significant safety to the procedure depends largely on a surgeon’s comfort level with phacoemulsification,” he says. “More seasoned surgeons tend to handle hard nuclei well, having gained experience in a time when cataracts were much more mature and phaco equipment was less advanced. For younger ophthalmologists encountering hard cataracts without adequate training, using a MiLoop might simplify the process. However, I question whether it justifies the cost and effort involved.”

Morgagnians may even call for using a supracapsular tile technique, Dr. Grayson adds. “The Morgagnians tend to have a very hard center, so you’re not going to be able to do a quadratic crack or a chop, because the nucleus is floating in the free cortex. You have to be comfortable using a supracapsular tilt technique to get out those hard centers,” he says.

The integrity of the zonules further influences how the surgery continues, say surgeons.

“If the zonules are compromised, it poses significant issues during surgery,” Dr. Grayson says. “As long as the capsule remains intact with healthy zonules, you can perform the procedure effectively. For Morgagnian cataracts, the zonules can sometimes be partially dissolved, resulting in subluxation.”

If zonules are lost, support is compromised and capsular tension rings might not be feasible.

“When there’s any indication of compromised zonules, you should be comfortable using capsular support hooks—not just iris hooks, but capsular support hooks as well,” Dr. Grayson says. “It’s important to place them early to ensure good capsular stability during phacoemulsification. My threshold for using capsular hooks is whenever I notice too much wobbling or instability; I’ll insert them early, even before starting the phaco procedure, to ensure stability.”

Surgeons must then decide whether to proceed with an anterior chamber lens or a sulcus-sutured fixated lens. “I have to determine whether there’s enough stability to insert a posterior chamber lens in the bag or if you need a sutured option,” he continues. “We often discuss devices like Ahmed segments that can be sutured in the bag. While they have benefits, they’re labor-intensive and can lead to potential complications, such as suture erosion. In some instances, it may be better to leave the situation as-is and schedule a secondary lens fixation after inflammation from the initial cataract surgery has cooled down.”

Traumatic

Traumatic cataracts present unique challenges, and can develop over time or quickly.

“Some traumatic cataracts are obvious, and when examining the patient, you can observe signs of negative dehiscence, and you may gather a history of trauma, which helps in planning the surgical approach,” Dr. Grayson says. “If you identify localized zonular absence, you should plan to place capsular support hooks in that area. For smaller dehiscences, 90 degrees or less, you might get away with simply placing the lens with a haptic in that area or using a capsular tension ring. However, for larger areas of zonular absence, a more extensive surgical plan may be necessary, possibly involving sutured segments.”

He says to prepare for unpredictability. “The trickier traumatic cataracts are the cases where you’re uncertain about the extent of trauma until you’re in the operating room,” Dr. Grayson says. “If you know going in that this is going to be a tough case, you should block the patient. It’s unpredictable—sometimes you can do a perfect case and still have some vitreous prolapse around the missing zonular areas. You have to be prepared for the lens to totally try to go south if there’s enough trauma, so in those cases, it’s wise to support them with capsular hooks. A supracapsular technique is generally preferable to capsular cracking or chopping, as it reduces stress on the zonules and minimizes the risk of the lens migrating posteriorly. By using viscoelastic below the nucleus, you create a barrier to protect the capsule and facilitate the phacoemulsification process in the iris plane.”

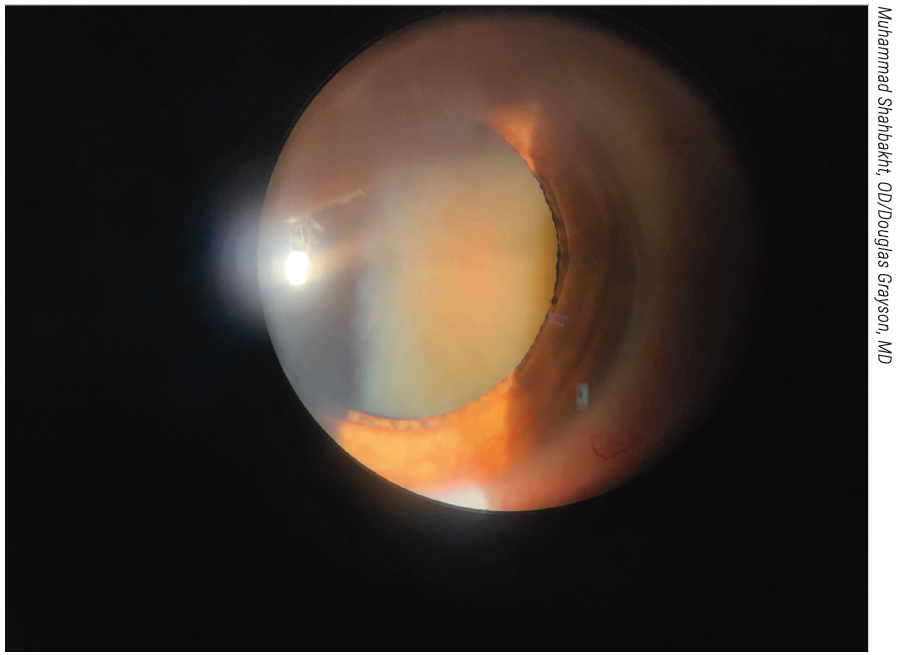

|

|

Shown here is a traumatic cataract with iridodialysis and zonular loss. Experts recommend using capsular support hooks in these situations and they may even consider involving retina colleagues to perform a pars plana lensectomy. |

Dr. Maltry says ultrasound biomicroscopy could be beneficial, and she doesn’t rule out consulting retina colleagues. “For rapidly developing traumatic cataracts, I often worry about a possible defect in the lens capsule, whether anterior or posterior,” she says. “If available, using UBM can help assess if the lens capsule is intact. If it appears that the posterior capsule is ruptured, I might consult with my retina colleagues for a potential pars plana lensectomy, as there’s a good chance the lens may fall backward anyway.

“Assessing the anterior capsule can be trickier since quickly developing cataracts tend to become white, obscuring the reflex and making it difficult to evaluate,” she continues. “If there’s lens material exposed to the anterior chamber, the inflammatory system will begin to react to that, which can lead to phacoantigenic inflammation and potentially glaucoma.”

Again, staining is a key step. “For rapidly developing traumatic cataracts with an anterior capsule rupture, I usually stain the capsule with trypan blue to identify the area of the rent,” recommends Dr. Maltry. “Depending on its location, I might use a cystotome or micro scissors to create the best possible capsulorhexis. Although the shape may not be perfectly round, the goal is to create enough access to remove the lens. Most of these cataracts are soft, allowing for aspiration or minimal phaco energy during removal once the capsule defects are identified.”

In the case of a white traumatic cataract, Dr. Maltry suggests a B-scan to make sure there’s no posterior segment pathology as well.

Christmas Trees and More

Christmas tree cataracts are particularly beautiful, resembling iridescent Easter grass, says Dr. Maltry.

“They’re classically associated with autosomal dominant myotonic dystrophy, a genetic disease affecting the muscles,” she says. Symptoms can include cataract development.

“When I encounter patients with this type of cataract, I inquire about muscle spasms, which is common in myotonic dystrophy,” continues Dr. Maltry. “However, while many patients with myotonic dystrophy may have Christmas tree cataracts, less than 20 percent of all Christmas tree cataract cases are due to this condition. Most cases are unrelated to systemic illnesses and are a fascinating example of protein crystallization in the lens.”

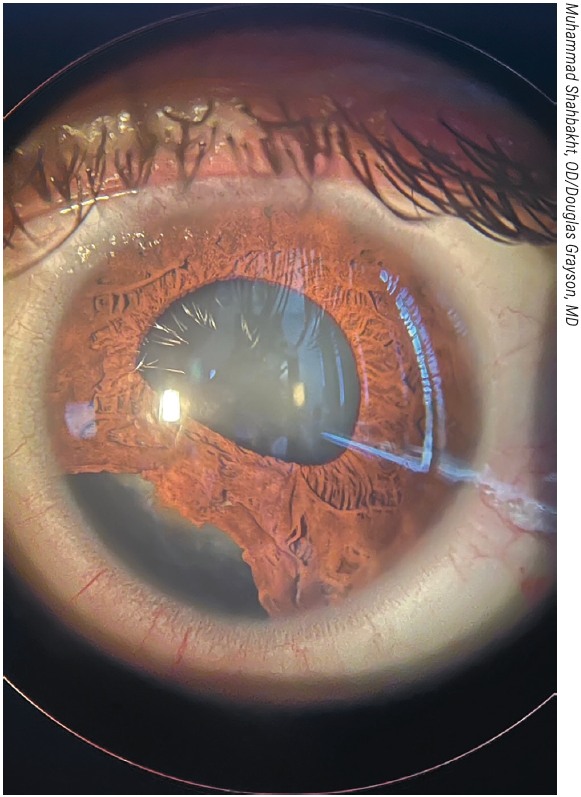

|

|

Patients with myotonic dystrophy may exhibit Christmas Tree cataracts, the appearance of which is due to the crystallization of proteins inside the lens. Although they look unlike other cataracts, they behave similarly and are typically soft and easy to remove. |

Patients with Christmas tree cataracts report symptoms similar to other cataract types, such as blurriness, glare and halos. “When they present, their symptoms don’t help differentiate between cataract types, but these cataracts can be visually significant,” she says. “If a patient has a Christmas tree cataract along with other types, it appears to compound the visual challenges, behaving similarly to any other cataract.”

Although their appearance makes them special, these cataracts are typically soft and manageable, so they aspirate pretty easily, says Dr. Grayson.

Other challenging cataracts Dr. Grayson offers tips on include:

• Marfan’s syndrome. “In patients with Marfan’s syndrome, cataracts often present with subluxation,” he says. “While some surgeons opt for complex techniques involving capsular support hooks and sutured Ahmed segments to place a posterior chamber lens, I sometimes find it less traumatic to call in a retina specialist to perform a pars plana lensectomy to remove the lens entirely. The incision is small, and you can bring the patient back another day to insert an ACIOL or a sulcus-fixated lens using a Yamane technique. This decision ultimately lies with the surgeon’s discretion, but it’s vital to block these patients to manage the surgery effectively.”

• Congenital posterior polar cataracts. “In this scenario the biggest risk is having a posterior capsule attachment to the cataract, so that when you remove the cataract, you also remove a chunk of the posterior capsule and have a risk of vitreous loss,” he says. “So traditionally, we’ve always said to try to avoid hydrodissecting aggressively in those cataracts, because if you create a fluid wave and you hydrodissect and you blow out the posterior capsule before you’ve taken the nucleus out, you have a high chance of the nucleus dislodging posteriorly as soon as you go in because it’s almost like a trap door.”

• Anterior cortical cataracts. These can occur in patients with atopic disease. “The anterior capsule could be very stiff, and we use 25-gauge retinal scissors to make cuts in some fibrotic tissue that may be on the anterior capsule, with the goal being to try to come around as consistently as possible to create a continuous, curvilinear capsulorhexis,” Dr. Grayson says.

Dr. Grayson consults for Alcon, Johnson & Johnson Vision, AbbVie, New World Medical and Glaukos. Dr. Maltry has no disclosures.