Here, three surgeons and a practice administrator, all known for their effective use of limited resources both in the office and in the operating room, offer a host of practical suggestions for not only surviving, but thriving in the midst of challenging times.

Maximizing Clinic Efficiency

Nothing undermines efficiency—and increases costs—like bottlenecks in the office. (This is especially true given the increasing paperwork demanded by insurance companies and government regulations.) These strategies can help minimize day-to-day problems and delays:

• Make it easy for doctors and staff to track office activity. “Knowing what’s happening throughout the practice at any given moment is very helpful,” notes Mark M. Prussian, MBA, who has served as administrator of two large ophthalmology practices since 1989. “It helps us juggle the workflow; it tells me who’s available to handle pharmacy calls, and so forth. If our office had no ceiling, I could look down from above and see what was happening in every exam room, but our EHR system does this for us; it’s part of the patient-flow management software. We can see onscreen where the patients are, where the doctors are, where staff members are, what’s happening in each exam room and how long someone has been in the exam room with a given patient. You can see that one patient is almost ready for the doctor; another is having a laser treatment with the doctor, and they’ll be done in two minutes; and so forth.

“To make the most of this, we’ve placed computers in as many locations as possible, including tech and nurse stations, so everyone has access to this information,” he says. “Of course, you have to log in for HIPAA compliance, but once you do, that window stays open in the background. So, the first thing you see is what’s happening in the clinic at that moment. I really think this is one of the best benefits of our EHR system. It helps us make the most of our resources.”

• Delegate to technicians. “I’m a big fan of technicians, both in the clinic and in surgery,” says R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, La., and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Louisiana State University School of Medicine in New Orleans. “Our technicians are trained on the job to have multiple skills. They do refractions and they understand how to use the slit lamp, even though they’re not qualified to do the examination. It streamlines things if I walk into the exam room and everything I need is there on the chart, except the slit lamp exam and retinal exam.

“Furthermore,” he continues, “most of our technicians are proficient at scrubbing in for surgery. They’re multitalented, and they understand the big picture—not just what’s going on in the clinic, but what’s happening in the OR. I think that helps them counsel patients better. Being able to have our technicians handle so much is a plus for us.”

• Be proactive about non-generic prescriptions. “Pharmacists and patients seem to be resisting ‘Do not substitute for generic’ orders more frequently than in the past,” notes Mr. Prussian. “They call us and say, ‘Are you sure? This medicine is so similar to that one … ’ Of course, our doctors only prescribe patent medications if they have a good reason. If the ordering doctor is available at the time the call comes in, he or she may get on the phone and lecture the pharmacist about the difference between the patent medication and the generic. If the doctor isn’t available, we may just go into the e-prescribing software and deny the request for a generic.

“Because this has become more of an issue, we’re planning to try printing a brochure that we can hand out, explaining why generics are not always as good as patent medications,” he says. “We’ll also add the explanation to our website, do a Facebook post about it and put it in our blog and our e-newsletter. Hopefully, by tackling the issue before patients take a prescription to the pharmacist, we’ll reduce patient unhappiness and be fielding fewer of those time-consuming phone calls.”

• Keep trying new things. “Trying new things is part of our office culture,” adds Mr. Prussian. “That includes frequently rearranging the office layout to see if we can improve it. For example, we generally start our in-office care with an autorefraction, so we keep tweaking the location of those instruments to see what works best for patient flow and is easiest for patients. It’s one way we challenge ourselves: What can we do better this week?”

Keeping Patients Coming In

To manage this, a practice must keep current patients’ experience positive, do everything possible to prevent missed appointments, and be effective at attracting new patients.

• Use the computer to customize paperwork. “We do this using a Microsoft Word merge program,” explains Larry E. Patterson, MD, medical director and surgeon at Eye Centers of Tennessee. “Our staff type in the patient’s name, age, allergies, which eye we’re operating on, type of surgical procedure and surgical date and time; the computer prints out 19 pages of fully customized paperwork, both for the patient and the surgery center, including consent forms and patient instructions. We’ve all had the experience of going to the doctor and receiving instructions that are a copy of a copy of a copy. The paper looks old and faded. Here, everyone gets a newly printed, customized bunch of paperwork. It’s efficient and it makes our practice look good.”

• Pre-appoint all patients before they leave the practice. “Doing this ensures that they have their next appointment set up, even if the appointment is a year later,” says Mr. Prussian. “Patients can easily forget to schedule later on, turning a one-year period into 18 or 24 months. Having the appointment already in the system allows us to remind them at the appropriate time. Of course, we will let people skip this if they insist on it.”

• Use your EMR system to alert you when a patient has not come in within an appropriate interval. “Even if we give patients an appointment and remind them, it doesn’t mean they’ll show up,” notes Mr. Prussian. “So, for example, we’ll have the computer generate a list of people with a glaucoma diagnosis who have not been in in the past year. Then, when the staff has a lighter workload on a day most of our doctors are in surgery, one person will call the patients on the list and say, ‘I’m calling on behalf of Dr. So-and-so; he’s noted that you missed your six-month glaucoma check. He has an opening next Thursday at 3:00; can we schedule that now?’ Overwhelmingly, patients agree to come back in.”

• Consider promoting your services and special events on Facebook. “I continue to find that regardless of what I try as a way to advertise our LASIK services, Facebook and Google AdWords outperform any other medium that I’ve tried buying over the past couple of years,” says Mr. Prussian. “Today it’s challenging to reach potential patients who don’t have a landline telephone, read newspapers or even watch live television any more. Facebook is one good way to reach them. You put up a witty posting and pay Facebook to find your demographic, such as people who ‘like’ us on Facebook, or have certain interests, or live in a given area. It’s pretty intuitive. Even better, it’s very easy to track the results.

“For example, I recently decided to advertise a LASIK seminar to a market I had never previously targeted,” he continues. “I hadn’t done much with country radio, so I thought it might be a way to reach new people with our message. We spent $3,000 on a one-month country radio campaign; at the same time, we spent $350 on Facebook ads, which took you to a registration page. About 80 percent of the people who showed up registered online through the Facebook ad; only about 20 percent heard about it on the radio station. The Facebook ad cost $350 and produced four times the response of the $3,000 radio ad.”

• Simplify your advertising. Mr. Prussian notes that a straightforward, simple message is more likely to get a response. “The word LASIK has become sort of generic, like the word Kleenex is to facial tissue,” he points out. “So, our advertisements generally just mention LASIK, because I believe the public equates that with improving your vision. When the patient is in the office, we do the examination and explain that he has cataracts or glaucoma or would be a great LASIK patient. But our message is targeted to say LASIK. It’s simple and effective.”

• If you have an optical shop, have the patient pick up his glasses prescription there. Many surgeons generate additional income by having an in-office optical shop. In that situation, it’s helpful to encourage patients to at least spend a few moments in that part of the practice so they’re aware of the option of purchasing their glasses without having to make an extra trip to another location. One way to accomplish that is to have patients’ lens prescriptions print out in the optical shop for them to pick up.

“This is easy to arrange if you’re using electronic medical records,” says Mr. Prussian. “If the patient picks up the prescription in the optical shop, he’s more likely to purchase the glasses from you. We also have the doctor check any appropriate boxes for items such as UV protection or anti-reflective coating that he believes are medically appropriate; the optician then explains the reasons for those recommendations to the patient.”

Managing Costs

This can be a challenge, especially if you don’t want to undermine the quality of patient care.

|

• If your EHR system handles many of your mailings, consider not using a postage meter. “When the volume of mailing you’re managing in-office drops below a certain level, it’s more cost-effective not to use a postage meter,” says Mr. Prussian. “Instead, it makes sense to have a trustworthy staff member simply buy stamps at face value in the post office and keep them in a safe place. Ten years ago we sent out several thousand pieces of mail a week. Now our computer system sends out patient statements, so we only send out 200 to 300 pieces of mail each week. In this situation I’ve found that it’s a better value not to be locked into a postage meter contract and have all of the expenses associated with that.”

• Don’t focus solely on the cost of supplies. “Surgeons often ask about reducing the cost of surgical supplies,” notes Richard J. Ruckman, MD, president and medical director of The Center for Sight in Lufkin, Texas. “However, supplies are the smallest part of the cost of doing business in the ASC. Salaries are the biggest cost, typically 43 percent of the cost of doing business; overhead is second, typically 33 percent; and supplies are third, at about 23 percent. Sometimes someone worrying about the cost of a particular supply overlooks how long it takes to do the surgery, or how many people it takes. So it’s important to remember that there’s more than one way to reduce costs.”

• Don’t scrimp on autoclaves. “Make sure you have adequate autoclaves to handle your volume,” says Dr. Ruckman. “This is not the place to try to save money. Any problems that arise as a result of incomplete disinfection could cause major time and energy drains, in addition to putting patients at risk.”

Surgery: Planning Ahead

“A good way to define efficiency is: maintaining or developing the highest quality and taking the shortest amount of time—without accepting unnecessary risks,” notes Dr. Patterson. “In practical terms, to be efficient in the OR, you need to reduce all aspects of the operation to their most essential elements. If you have a 20-step procedure and you can reduce it to a 10-step procedure, you’re not only allowing things to happen more quickly and more smoothly, you’ve just eliminated 10 things that can go wrong. So it’s worth stepping back from time to time, looking carefully at the process, and asking yourself: Is there a reason we do each of these steps?

“Generally, I think a cataract surgeon with a single OR should be able to do about four cases an hour,” he continues. “If you have two operating rooms, you should be able to manage five or six cases an hour, going back and forth from room to room. I often talk to surgeons who have two rooms and are only doing three cases an hour. That’s a huge waste if they’re routine cataract cases. In fact, if you’re doing less than that—two cases an hour—then you’d probably be better off financially just staying in the office and seeing patients. That’s not a business model that will work.”

Doing a number of things ahead of time will help make surgery go as smoothly as possible:

• Hire an experienced surgical coordinator. “It’s important to have one or two people, depending on how big your staff is, to focus on managing all the issues surrounding surgery,” says Dr. Patterson. “Your surgical coordinator can do preop testing and consultation, insurance precerts, scheduling, assembling the IOL power calculations, doing phone calls with the patients preop and postop and coordinating with your surgery center. Depending on your setup, the coordinator may also be able to go into the OR and help with turnover. This person’s job is to make sure everything goes as smoothly as possible the day of surgery, so there aren’t any surprises. This can have a real impact on your efficiency.”

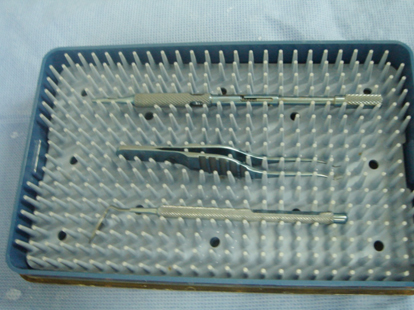

• Prepare instrument packs ahead of time. “It’s efficient and cost-effective to prepare sterile peel-pack kits containing the instruments you need for a particular surgical situation,” says Dr. Wallace. “We create a cataract pack; we also have kits for special circumstances such as when a patient needs an LRI, or I need to perform a vitrectomy. Because we have the kits, we don’t have to assemble all these separate tools and sutures. Everything is ready to go whenever it’s needed.”

| ||||||

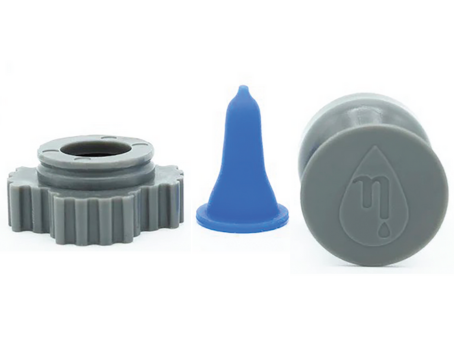

• Have a compounding pharmacy combine your preop drops. “We have our dilation drops, a non-steroidal and an antibiotic all compounded together,” says Dr. Patterson. “There are places that will do this for you pretty inexpensively. Once this is done, you just have to put in a few drops; you don’t have to go back to the patient over and over again. Of course, we still keep individual drops such as the dilating drops available in case we need more of them.”

• Aim to schedule left or right eyes together. “Since most of us operate temporally, I think it’s important to try to do all your right eyes together and left eyes together so you don’t have to change the OR setup back and forth,” says Dr. Patterson. “That’s something you can do ahead of time that will make your day run smoother. And, if you have two ORs, you can set up one OR for right eyes and the other for left eyes.”

• Set up the OR so you can easily switch from left to right eye with minimal rearrangement. “Even if you try to group your eyes so you do all left or right eyes at once, things often get out of order,” notes Dr. Ruckman. “We arrange our ORs so that we can switch from a left eye to a right eye with minimal work. (See example, facing page.) The less you have to change, the smoother your flow will be throughout the day.”

| ||||||

• Have a monitor in the OR that allows others to view the surgery. “It’s important to have a monitor in the OR so the anesthesia professional can see how the surgery is going,” says Dr. Wallace. “He or she will know if there’s any unusual eye movement, and be able to communicate effectively with the surgeon in regards to what medications to give at what time.”

Dr. Ruckman adds that the monitor has other benefits as well. “Because my assistant is not looking through the microscope, she may not know exactly where I am in the procedure,” he says. “She can actually follow the procedure more easily on the monitor and have my next instrument available immediately. The circulator is constantly aware of where we are in the procedure and can better anticipate a need for extra instruments or supplies. The monitor also lets our transporters know when to be in position to move the patient from the room.”

• If possible, arrange your OR so you can see the preop and postop areas. “We have two identical operating rooms, and everything is compact enough that I can stand in one position and see everything going on,” says Dr. Ruckman. “I think that adds to efficiency, because I don’t have to run all over the building to know what’s happening in the pre- and postop areas. Obviously, not every building design will allow that, but it’s an advantage if you can arrange it.”

• Schedule more complex cases later in the day. “Obviously, more complex cases are likely to require more time and can be more disruptive to the schedule,” notes Dr. Ruckman. “Scheduling them later in the day minimizes the disruption and gives us more time to focus on the patient. It also keeps the other patients and their families calmer; they get more anxious when their surgeries are delayed.”

• Save detailed postop instructions for post-surgery. “We provide written preop instructions and a review of postop care in the clinic prior to surgery,” says Dr. Ruckman. “However, we’ve found that it’s much more efficient to provide the detailed postop instructions only in the recovery area; otherwise we end up providing them twice.”

• Don’t assume all OR personnel have to be RNs. “I’ve seen some places where everyone in the OR other than the surgeon is a registered nurse,” says Dr. Patterson. “That’s overkill. Nurses have to do some things, including putting in eye drops and giving medications.

|

• If possible, share staff between clinic and ASC. “Our surgery center is part of our clinic,” says Dr. Ruckman. “We have a full-time RN director in the ASC, but the clinic and ASC share staff. As a result, the staff in the surgery center know the patients because they’ve been working with them. That helps things go smoothly.”

On the Day of Surgery

These strategies will help get things off to a good start:

• Be on time. “This is an important point for doctors, because staff are usually pretty good at this,” notes Dr. Patterson. “The surgeon may feel it’s his prerogative to be a little late, but that will undercut your efficiency and discourage your staff.”

In fact, Dr. Ruckman sees an advantage to getting there ahead of time. “Arriving a few minutes early allows me to check both operating rooms to see that the microscopes are working properly and everything is set up correctly,” he notes. “This saves time by preventing problems later.”

• Prepare a “summary sheet” at the beginning of the surgical day. “Once we know what the schedule is, my nurse prepares a sheet showing what we anticipate the order of cases will be,” explains Dr. Ruckman. “I then add the proposed lens that I want to use for each case, although I don’t list the lens power; we always go back to the original document to identify the power in the OR immediately prior to the procedure so there’s no room for transcription errors.

“The sheet also includes other elements that are relevant to the case,” he continues. “First of all, is it a complex surgery? Listing that helps ensure that the billing department will bill it as a complex case. Am I going to use special instruments? Will there be a pterygium? Will I need Trypan blue? We do our best to anticipate this so the staff is ready and expecting it. I also make notes about anesthesia; whether I think the patient is anxious and needs more sedation, or how the patient reacted during the first case and how this might affect the second eye. The list follows the nurses and technicians from room to room, but it’s also posted in all the rooms and preop areas, on a clipboard where only staff can see it, so everybody knows what’s happening when.”

• Have the first three patients arrive at about the same time. “At the beginning of the day we have the most staff available to help in the preop area,” explains Dr. Ruckman.

|

• Keep the patient on one stretcher from start to finish. “Once the patient comes in he’s put on a stretcher,” says Dr. Ruckman. “We hook up the blood pressure and vital sign monitors in the preop area. The monitor stays on the stretcher, so once the patient is hooked up, we don’t have to unhook anything until the patient is in recovery. We also use leads on each wrist to monitor the heart rate, which saves us from having to expose the chest to put on chest leads.”

“Moving the patient as little as possible saves time and reduces back strain,” notes Dr. Patterson. “When it’s time for surgery, we just recline the stretcher, go straight into surgery, do the surgery with the patient on the stretcher and then move the stretcher into postop. I’ve seen lots of surgery centers where they have a standard OR table and they have to move the patient from the stretcher to the table and back to the stretcher. That’s not necessary.”

• Adjust the patient in the preop area. Adjust the head, the positioning and the height of the table before you go into the OR,” suggests Dr. Patterson. “The nurses or their assistants can do this.”

During the Surgery

To keep things moving smoothly and avoid unnecessary delays:

• Don’t wait until everything is prepared to bring in the patient. “The room doesn’t have to be completely set up when the next patient is brought in,” says Dr. Patterson. “I’ve seen the old hospital way of doing things; they wouldn’t let you bring the patient in until all of the equipment was set up and everything was ready to go.

|

• Have staff prep the patient. “One person in our OR preps the eye; then the technician who’s helping in surgery drapes the lid and lashes,” says Dr. Wallace. “When I come in, the eye is basically ready to go for surgery. Our technicians and RNs handle all of the preparation without anybody else needing to be present in the room.”

• Emphasize constant communication. “Communication should occur as the patient is transferred from one area to the next, so the RN is aware of what is going on,” says Dr. Ruckman. “Furthermore, communication has to happen both from the top down and the bottom up. Everybody needs to be aware of what’s going on with each patient, and not being afraid to point out or question anything. Each person is responsible for his or her own tasks, but everyone should also be aware of what everybody else is doing.”

• Don’t skip the pre-surgery “time out” in the name of efficiency. “This is one government regulation that I’ve found to be good,” says Dr. Ruckman. “Before you start the case, you’re supposed to take a time out and get everyone to focus on the patient for just a minute. Everybody stops and agrees that we have the right patient, the right diagnosis, the correct eye, and allergies are identified. Everybody verbally states that they agree, and then we proceed with the surgery.

|

• Adjust the microscope so you can sit back in the chair. If the surgeon is uncomfortable or in pain, efficiency will suffer. “I’m a big proponent of being careful with surgeon posture,” says Dr. Wallace. “I recommend tilting the microscope 45 degrees toward the surgeon; that allows you to sit back in the chair as you work. Some of these cases unexpectedly go on for a fairly long time if you have a complication, and the surgeon doesn’t get to stand up and walk around the room and stretch. The surgeon has to stay in that position until the case is finished, which could be an hour or more.

“I’ve had many doctors come up to me and tell me they were ready to retire as a result of physical injury, until they tried switching to a 45-degree tilt,” he adds. “When we were operating superiorly we couldn’t do this; but now that we’re operating temporally we can tilt the patient’s head 45 degrees. Jim Gills, director of St. Luke’s Cataract & Laser Institute in Florida, uses this technique; he even puts a bolster under the patient’s opposite shoulder, so the whole body of the patient is tilted 45 degrees. We do this as well.” (For more on this, see Dr. Wallace’s article in the Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery.1)

• Include potential time-saving surgical techniques in your repertoire. “For example,” says Dr. Wallace, “when performing cataract surgery I’m sometimes successful with cortical cleaving hydrodissection, described by Howard Fine in 1992. With this technique you try to inject the BSS not just around the nucleus, but the cortex as well; a successful attempt is confirmed by a peripheral fluid wave. When this works, removing the nucleus also removes the cortex, so you can skip the cortical irrigation and aspiration step. I’m not able to make this work 100 percent of the time, but when it does work, it’s more efficient.”

• Be a part of your team. “Many surgeons disappear for a few minutes between cases,” notes Dr. Patterson. “They may go back and sit in the lounge and wait to be called. That’s not efficient, and it doesn’t encourage the rest of the surgical team, who continue working to get ready for the next case.

|

• Don’t deal with other concerns during surgery hours. “This relates to the previous point,” notes Dr. Patterson. “I’ve talked to consultants who say that surgeons are notorious for taking phone calls from their stockbrokers, families or friends between cases. They don’t keep their minds focused on what’s happening in the surgery center. This is discouraging for the staff and a potential time sink, so if you’ve got a morning blocked off to do surgery, just do surgery. Leave your cellphone in your office or in the locker room. If there’s an emergency, people will be able to get hold of you. Let the rest of it go.”

• Don’t wait for the end of the case to begin preparing for the next case. “Although we have everything we need for cataract surgery on the mayo stand, which in our case is integrated with the phaco machine, we also have a back table where a staff member opens packages, sets things up and loads the lens,” says Dr. Patterson. “We don’t wait for the case to be finished before one of the staff begins clearing off the back table. While we’re putting the implant in, the back table is being cleared and prepared for the next case. This saves considerable time.”

Postop Efficiency

These strategies can help prevent bottlenecks and extra post-visit phone calls:

• Don’t keep patients in postop longer than necessary. “We have a very short postop period,” notes Dr. Patterson. “It helps that we don’t routinely use patient IVs; we just give patients mild oral sedation. Partly for that reason, most of our patients only remain in the postop room for 10 or 15 minutes. If their vitals are normal, they’ve been able to drink some juice and they feel OK, we put them in a wheelchair and let them go home. This avoids tying up space. Even if space isn’t a problem, the more people you have sitting around, the more staff you have to have, watching and tending to them.

“Our ideal is for someone to come in and leave within an hour to an hour and 15 minutes,” he adds. “We achieve that most of the time. Not always, but most of the time.”

• Have printed postop instructions for the patient and family member. Since the patient could still be somewhat amnestic, we make sure that all instructions are printed and request that a family member be present at the same time,” says Dr. Ruckman. “Everything is printed for the family member as well, which reinforces what to do and what to expect.”

When Management Resists

Dr. Ruckman, who along with Drs. Wallace and Patterson teaches the surgical efficiency course at the annual American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting, notes that questions from the audience often involve how to overcome a hospital or ASC’s inertia. “Doctors,” he says, “will report that the OR director tells them, ‘We can’t do it that way. We never have.’

“A good way to address this,” he continues, “is to present that person with benchmark data showing that the surgery and patient flow can be done differently without undercutting quality of care, resulting in improved efficiency and time-savings. Studies conducted by the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care, for example, show how long a cataract surgery case should take, and how long the patient needs to be in preop and postop, as well as providing details about the reasons for the efficiency. Typically those data are based upon several hundred thousand cases.

“For instance, one study of cataract surgery found that the average facility time—the time from the moment the patient walked into the facility until they left—was 119 minutes,” he says. “The average preprocedure time was 83 minutes. Operating time was 15 minutes; discharge time was 21 minutes. This gives you some numbers to work with based on a national standard. So if there’s a bottleneck in the facility you’re using, you can say, “This is a national comparison; why can’t we meet this benchmark?” You’re providing concrete evidence that the procedure can be done in less time.

“For example, an OR director might insist that patients get completely undressed for surgery, put on a gown, and stay in recovery for at least two hours,” he continues. “But the benchmark data show that patients can remain fully dressed for the surgery, and once they meet discharge criteria they can leave in much less than two hours. It gives you some basis for comparison, and it proves that you can get a patient through a facility in two hours instead of three or four, and still provide quality care.

“Unfortunately,” he adds, “there’s not a lot of this kind of data out there. The AAAHC data is only available free of charge to those who participated in the study. However, you may be able to buy the study, which might be worthwhile if a facility is causing an unnecessary reduction in your efficiency.”

Efficiency in Perspective

“Efficiency is a double-edged sword,” notes Dr. Wallace. “Ironically, taking less time to do a procedure can lead to further cuts in reimbursement. But if you want to handle more patients, you have to consider at least some steps to make it possible for those extra patients to be taken care of without working into the night and losing good quality staff because they don’t like their hours.”

Drs. Wallace and Patterson offer a few closing pieces of advice:

• Don’t take chances. “Efficiency is good for the patient,” says Dr. Wallace. “However, we can’t throw the baby out with the bath water; we have to produce very good results. So if surgeons feel overwhelmed or out of their comfort zone when trying to be more efficient, they should take it slowly. Improving efficiency shouldn’t mean taking chances. The last thing any of us wants is to sacrifice patient visual results.”

• Don’t worry about efficiency until you’re really good at what you do. “To be efficient, you must first be proficient,” notes Dr. Patterson. “You have to be good at what you do, first and foremost. If you’re coming straight out of residency, you need to become good at doing the surgery; don’t worry about efficiency. Complications are very inefficient! Of course, that’s not the main reason to avoid complications, but if you’re trying to be more efficient, minimizing complications should be high on your list.”

• Don’t try to increase efficiency by working faster. “Efficiency will lead to speed, but speed will not lead to efficiency,” Dr. Patterson notes in closing. “Rushing will not help; it will just cause more problems. If you’re efficient and you do things properly, surgery will go faster. But simply trying to work faster may backfire.” REVIEW

1. Wallace, RB. The 45 degree Tilt: Improvement in surgical ergonomics. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999;25:2:1-3