|

The Problem with PXF

In pseudoexfoliation disease, fibrillar material is produced by cells in the anterior segment, possibly in response to oxidative stress. Tiny clumps of that fibrillar material are released into the extracellular space; some of them end up deposited on structures inside the eye, including the zonules, the trabecular meshwork, the pupillary margin and the anterior surfaces of the lens and capsule. The increased intraocular pressure seen in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma is presumed to be caused by clogging of the trabecular meshwork. This may be the result of fibrillar deposits, but the disease is also accompanied by pigment release from the iris, possibly caused by the iris rubbing against the deposits on the lens capsule. That released pigment may also contribute to blocking the trabecular meshwork.

One of the difficulties with pseudoexfoliation syndrome is that in contrast to open-angle glaucoma, where pressures typically rise slowly and insidiously, pressures can rise dramatically even within a matter of months. This is dangerous because patients may not be seen for a year, and during that year their IOP may have gone up 20 mmHg. If the patient already has glaucoma, an increase that significant could occur within six months.

For that reason, these patients require very frequent follow-up. Unfortunately, patients themselves are usually not aware of the change in pressure, due to a lack of symptoms. Notably, patients with pseudoexfoliation tend to have worse diurnal control than patients without pseudoexfoliation.

|

Pseudoexfoliation can cause problems beyond glaucoma. Within the eye, there’s evidence that it can cause endothelial problems, such as corneal endothelium dysfunction, leading to corneal edema following cataract surgery; it can also affect the blood-aqueous barrier, leading in some cases to inflammation after surgery—sometimes prolonged—or cellular deposits on the lens postop. Deposits on the zonules can lead to weakening and subluxed lenses, and there is some questionable evidence that pseudoexfoliation may also increase the risk of cystoid macular edema. Beyond the eye, there’s evidence of systemic involvement, for example in systemic blood vessels. There’s conflicting evidence regarding whether the disease is associated with mortality.

Despite the evidence of a systemic connection, I wouldn’t necessarily notify the patient’s general practitioner if I found evidence of pseudoexfoliation syndrome, simply because the evidence of systemic danger is still very mixed. Obviously it’s important to communicate with a general practitioner when any patient has glaucoma—it’s simply good practice. But the possibility of a connection between pseudoexfoliation syndrome and systemic disease, mortality and stroke risk is still up in the air.

Diagnosing the Disease

Unfortunately, diagnosing pseudoexfoliation syndrome can be challenging; it’s a bit like detective work. Signs can be subtle, so even though the disease is commonplace it’s quite possible to miss it.

Normally, a clinical diagnosis of pseudoexfoliation is made at the slit lamp using biomicroscopy. Signs include:

|

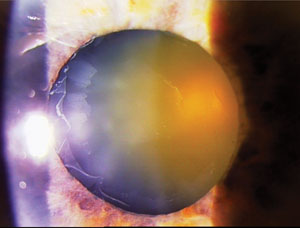

• Deposits on the anterior capsule, in a manner resembling a target. This is a classic sign. The “target” appearance is caused by the iris clearing a circular area on the surface of the capsule. Unfortunately, these deposits are normally only visible if the patient is dilated.

• Poorly dilating pupils. This may be the result of structural damage to the iris cause by the pseudoexfoliative debris.

• Peripupillary atrophy. This finding, which is suggestive of pseudoexfoliation, is indicated by a little transillumination defect in the peripupillary iris. Unfortunately, this is a fairly nonspecific finding, meaning that other conditions can cause it; however, it should arouse your suspicions.

• The age of the patient. Pseudoexfoliation typically occurs in patients over 65 years of age. However, it can occur in somewhat younger people; I recently had a patient in his early 50s who was diagnosed with this condition.

• Pigmentation beyond the expected level. I’ve never seen a patient with pseudoexfoliation syndrome who didn’t have a greater-than-expected amount of pigmentation in the angle on gonioscopy. I grade an angle’s pigmentation from 0 to 4+; if an angle is 2+ or higher, I usually start wondering whether the eye has pseudoexfoliation syndrome, even without any other classic findings. Of course, other things can cause pigment dispersion and pigment in the angle, but I certainly would consider the possibility that the patient has pseudoexfoliation.

• Asymmetry in the signs. With pseudoexfoliation syndrome it’s common to see an asymmetrical presentation of signs, including the amount of pigment in the meshwork and the glaucoma itself. So if one eye has 2+ pigment and the other eye has 1+ pigment or trace pigment, in my book that’s someone who is highly suspicious of having pseudoexfoliation syndrome.

The Cataract Connection

Pseudoexfoliation syndrome can have a direct effect on cataract surgery, in part because it affects the zonules. Pseudoexfoliation material coming off of the anterior capsule deposits all over the eye, including on the zonules, where it’s believed to trigger enzymatic degradation. The zonules become very brittle, causing them to snap and break. This is one of the most common causes of complications after cataract surgery. (Note: Because of this, subtle iridodenesis, phacodenesis and subluxed lenses are sometimes manifestations of the disease. However, many things can cause a subluxed lens, so I wouldn’t automatically assume that a subluxed lens was caused by pseudoexfoliation syndrome.) Because weak zonules make lenses mobile and difficult to remove, it’s crucial to note pseudoexfoliation syndrome before performing cataract surgery.

Suppose you discover that a cataract patient has pseudoexfoliation. The first question to ask is whether the patient has glaucoma. If the patient does have glaucoma, you should consider combining the cataract operation with a glaucoma procedure. But with or without glaucoma, the small pupil and weak zonules increase the likelihood of cataract surgery complications as much as ten-fold compared to a routine cataract procedure, so you need to be prepared with strategies to help you deal with these concerns. Useful tools include pupilary rings such as a Malyugin ring for small pupils; iris hooks or retractors; and capsular tension devices for zonular problems. Capsular tension rings may be especially useful when there is a lack of zonular support. In approaching cataract surgery, the surgeon may have to be prepared to fixate a lens to the iris or sclera, or even to use an anterior chamber lens.

Detecting pigmentation in the angle does require a very thorough, careful gonioscopic examination. Unfortunately, I believe some cataract surgeons skip a gonioscopic exam because the yield is felt to be too low to warrant it, but I gonio every cataract patient to look for signs. That requires both an undilated exam and a dilated exam to look at the anterior capsule and the lens itself.

Managing the Disease

Treating pseudoexfoliation patients is similar to treating POAG patients; medications and lasers certainly have a role, including selective laser trabeculoplasty and argon laser trabeculoplasty. Most people are not using the latter two options as first-line treatment, but in my practice we resort to them much earlier than we would have in the past. For example, I typically start these patients on medications; after one or two drops or classes of medications, I’ll go to SLT. Although study results in the literature have been inconsistent, I find that pseudoexfoliation syndrome can respond quite well to SLT. However, the effect of treatment seems to wear off a little earlier than with other patients, and that development may be signaled by a significant jump in pressure. So it’s a mixed blessing: These patients seem to respond to SLT better than POAG patients, but when the effect wears off, their pressures may rebound more.

Again, it’s important to treat these patients a bit more aggressively, so I would certainly consider escalating therapy more than I would with a POAG patient, and that would include surgical options. Any of the traditional surgical approaches we have available to us could be effective for treating PXF glaucoma. Of course, if the patient were to present with very advanced disease and uncontrolled pressures, I’d be more likely to head for surgery immediately, based on the urgent need to lower the pressures and achieve diurnal control.

Interestingly, we don’t yet know how effective some of the newer procedures like the Trabectome or iStent will be for treating pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. These approaches lower pressure by bypassing the trabecular meshwork walls, so in theory they might show the same level of efficacy as they do when treating POAG, but we don’t yet have a firm answer. My suspicion, supported by emerging data, is that these types of procedures work quite well compared to their efficacy with POAG. I would definitely consider all of the surgical options, including canaloplasty, trabeculectomy/ExPRESS and the iStent, depending on the level of disease and the target pressure that’s required.

Of course, a patient may have pseudoexfoliation syndrome but not show signs of elevated pressure or glaucoma. However, a patient in that category is at increased risk for glaucoma and needs regular follow-up, at least on a yearly basis. That individual’s risk of developing glaucoma over a lifetime can be anywhere from 30 to 50 percent. Often one eye gets involved first, but the second eye may also become involved many years later.

In any case, numerous studies have shown that patients with pseudoexfoliation syndrome have a higher risk of progression than patients who don’t have it. For that reason, I follow these patients more closely, and I’m often a little more aggressive in treating. I aim to get the pressure a little bit lower than I would for a POAG patient, and I might start treatment a little earlier than I otherwise would.

Secondary Angle Closure

One of the ways pseudoexfoliation syndrome can lead to glaucoma is through angle closure resulting from the weakened zonules associated with pseudoexfoliation.

Statistics indicate that about 10 percent of individuals with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma have shallowing of the lens leading to angle closure. To add further complexity, individuals with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma may have an open-angle component and then also go into angle closure over time because the lens has shifted. Patients in this situation require management dealing with both mechanisms. If the angle is sufficiently narrowed, laser iridotomy may be necessary.

|

Gonioscopy is key to discovering this problem, although anterior segment imaging such as optical coherence tomography and ultrasound biomicroscopy can be helpful as well. UBM is very interesting because it enables you to see the thickening of the zonules resulting from the deposition of the pseudoexfoliation material. (For an example, see p. 103.)

Another confounding factor is that it’s possible for a surgeon to note the angle closure but not realize that it was caused by loose zonules. For that reason, it’s important that whenever we encounter angle closure we consider the possibility that it’s a loose zonule case, whether the cause is pseudoexfoliation or another problem. Shallowing of the anterior chamber is a typical sign that loose zonules are a factor in the angle closure.

Pigmentary vs. PXF Glaucoma

Because both pigmentary glaucoma and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma involve pigment dispersion, it’s important to determine which one you’re dealing with. (Of course, both conditions could theoretically coexist in one patient.) Differences between the conditions include:

• Patient age. In clinical diagnosis pigment dispersion is typically found in young rather than older patients.

• Asymmetry. Asymmetry is usually more marked in pseudoexfoliation syndrome, while pigment dispersion usually has a more bilateral presentation, although there are exceptions.

• Amount and location of pigment. Both conditions can involve a fair amount of pigment, but with pigment dispersion glaucoma you’re more likely to find a greater amount of pigment in the angle than you generally see in pseudoexfoliation, as well as more pigment deposits on the iris and cornea. On the other hand, pigmentary glaucoma doesn’t produce the classic fibrillar deposits on the anterior capsule that we see with pseudoexfoliation.

• Location of transillumination defects. Mid-peripheral transillumination defects are seen more often with pigmentary glaucoma, as opposed to around the pupil in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma.

• The Krukenberg spindle. This is classic in pigmentary glaucoma; it’s much less often seen in pseudoexfoliation glaucoma.

Can We Clean the Meshwork?

Because pseudoexfoliation glaucoma appears to be caused by exfoliative debris clogging the trabecular meshwork, one approach that in theory might reduce the likelihood of increased pressure is simply cleaning some of the debris out of the meshwork.

This approach was actually tried many years ago; researchers used aspiration to unclog some of the blocked tissue.1,2 They had some nice early results, but the effect wasn’t maintained over the long term. Basically, they didn’t have any way to prevent the problem from recurring.

A similar effect might account for the pressure reduction seen in these patients from the cataract surgery itself. We know that cataract surgery can lower pressure in glaucoma patients, including those with pseudoexfoliation, and the higher the pressure, the greater the percentage drop we see. Some studies have suggested that the amount the eye is irrigated during cataract surgery makes a difference. This makes intuitive sense, because the more you irrigate during surgery, the more you’re clearing debris out of the meshwork. But again, this is an ongoing disease, so the debris will eventually reaccumulate. Thus, any relief achieved as a result of the cataract surgery is unlikely to be maintained over the long term.

Making the Best of It

Attempts to manage the disease by clearing debris from the trabecular meshwork highlight the fact that with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma, we’re managing the problem, not curing it. (Unfortunately, that’s basically true for any glaucoma at present.) Hopefully, that will change; evidence is strong that there is a genetic component to this disease, probably multifactorial. But despite a lot of work being done in this area, we’re not yet ready to address it at the genetic level.

In the meantime, it falls to us to protect our patients by making sure we don’t miss the sometimes subtle signs of pseudoexfoliation. Caught early and managed with care, we can prevent this type of glaucoma from stealing our patients’ vision. REVIEW

Dr. Ahmed is assistant professor at the University of Toronto in Ontario.

1. Jacobi PC, Krieglstein GK. Trabecular aspiration. A new mode to treat pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1995;36:11:2270-6.

2. Jacobi PC, Dietlein TS, Krieglstein GK. Comparative study of trabecular aspiration vs trabeculectomy in glaucoma triple procedure to treat pseudoexfoliation glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 1999;117:10:1311-8.