|

In recent years our team at Dalhousie University and collaborators have been conducting studies to determine the number of visual fields required in a given time period to determine different rates of progression with statistical validity. During the past five or 10 years, some data has been published regarding the frequency of optic disc examinations using photography or other, newer technologies. Generally, this data indicates that most practices conduct these examinations less frequently than is recommended by organizations such as the American or European Glaucoma Societies. However, we found very little data on the frequency of visual field exams, so we began looking into this. Not surprisingly, the frequency of visual field exams appears to vary tremendously from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and practice to practice.

This observation led us to attempt to determine how many examinations would be required in order to detect different rates of visual field progression. Obviously this is a complex question that can’t be definitely answered for a given patient without making a number of assumptions, but we felt that the question was important enough that it was worth attempting to answer.

Defining the Problem

In terms of putting this information to practical use, a key issue is: What rate of progression are we willing to tolerate in each individual patient? The impact of a given rate of progression on a patient depends on several factors, including how old the patient is, the patient’s life expectancy and how advanced the visual field damage is at diagnosis. For example, a moderate rate of progression might be acceptable in a 90-year-old patient with a life expectancy of five or 10 years who’s just been diagnosed and has very early damage. That individual would be unlikely to reach visual disability within his lifetime. On the other hand, that same rate of progression might be completely unacceptable in someone who’s diagnosed at age 40 with much more advanced damage—because the younger patient may have a life expectancy of another 40 or 50 years, more than enough time to suffer visual damage.

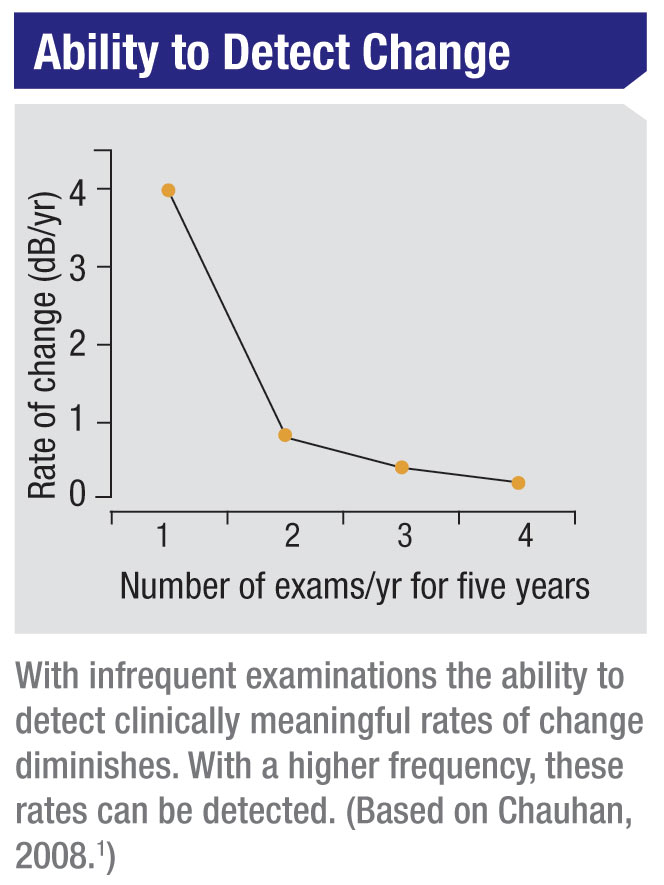

The problem is that our ability to detect different rates of progression

is limited by the number of exams we perform in a specific period of

time. If your goal is to detect a large rate of change, then you don’t

need to do many examinations over a given time period (for example, the

first two years after diagnosis); rapid change will be evident even with

a limited number of exams. However, if you hope to detect a smaller

rate of change, you’ll need a higher frequency of visual field exams

during that period. So, a 40-year-old patient with significant existing

damage would require more visual fields than a 90-year-old with early

disease and minimal damage, simply because you need to detect a slower

progression rate in the younger patient. For him, that slower rate is

likely to be visually significant; he has many more years for his vision

to deteriorate.

This is obviously most important with a new patient for whom you have limited pre-existing information. If a patient with glaucomatous visual field damage comes into your office with previous visual fields, you can probably get a good idea of how fast the disease has been progressing. But if you have no information, you’ll have to do a series of exams to determine the rate at which the damage is occurring. (This is primarily a concern with patients who already have glaucomatous visual field damage, as opposed to a patient with ocular hypertension.)

In terms of putting this information to practical use, a key issue is: What rate of progression are we willing to tolerate in each individual patient? The impact of a given rate of progression on a patient depends on several factors, including how old the patient is, the patient’s life expectancy and how advanced the visual field damage is at diagnosis. For example, a moderate rate of progression might be acceptable in a 90-year-old patient with a life expectancy of five or 10 years who’s just been diagnosed and has very early damage. That individual would be unlikely to reach visual disability within his lifetime. On the other hand, that same rate of progression might be completely unacceptable in someone who’s diagnosed at age 40 with much more advanced damage—because the younger patient may have a life expectancy of another 40 or 50 years, more than enough time to suffer visual damage.

|

This is obviously most important with a new patient for whom you have limited pre-existing information. If a patient with glaucomatous visual field damage comes into your office with previous visual fields, you can probably get a good idea of how fast the disease has been progressing. But if you have no information, you’ll have to do a series of exams to determine the rate at which the damage is occurring. (This is primarily a concern with patients who already have glaucomatous visual field damage, as opposed to a patient with ocular hypertension.)

In most cases, if the patient has a long life expectancy, you’d want to

know if his rate of progression is causing a loss of 2 dB per year or

worse—what we would consider a “fast progresser.” (Even a loss of 1 dB

per year in some patients could ultimately be catastrophic.)

The reality is that the accuracy of any decision you make regarding progression in a patient will be directly proportional to the amount of data you have. If you have five years worth of data and you’ve got two to three good-quality visual fields per year, you’ve got a pretty good idea of what’s happening to that patient. If you’ve done three tests over a period of five years, you may not have any idea what’s going on.

How Many Visual Fields?

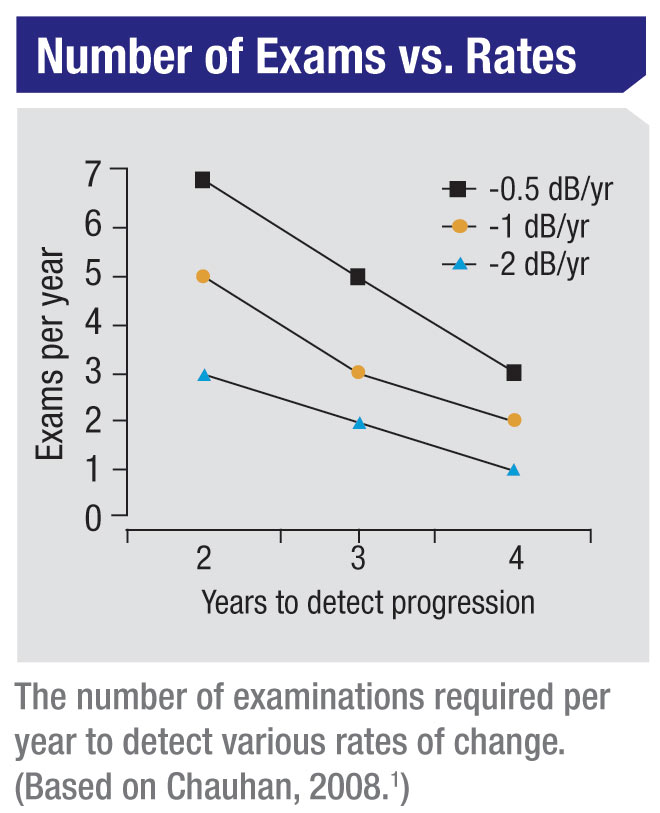

Given these concerns, we wanted to provide some practical guidelines regarding the number of visual field exams that are necessary to accurately detect a given rate of progression. So, we did a series of analyses to come up with the number of examinations that would be required to detect different levels of progression.

What our statistical analyses found is that six visual field exams have to be performed during the first two years in order to detect a rate of progression of about 2 dB per year—sufficient to threaten a patient’s vision over time, but not easily determined with a smaller number of exams during the same amount of time. Again, a really fast rate of progression can be measured with fewer tests; but a rate of 2 dB per year (or slower) cannot reliably be determined without doing six tests in two years’ time.

For example, suppose a new glaucoma patient comes to see you. The first visual field you perform will give you a pretty good idea of whether the visual field is damaged. That visual field should be repeated to ensure the accuracy of your baseline. If those two exams indicate the presence of damage, then it becomes important To determine whether or not the individual is a fast progresser. (This is true even if you begin treatment to lower the intraocular pressure; some individuals will continue to progress quickly despite being treated.) If that patient is then followed with a total of six visual fields over the two years, the ophthalmologist can get a good idea of how fast that patient is progressing. Once that rate of change has been determined, the need for more serious treatment and monitoring can be decided in light of the patient’s visual field damage-vs.-age plot. (Note: Commercially available software such as the Humphrey Progression Analysis system can work well for the analysis; the issue is having a sufficient number of visual field tests for the analysis to pick up the progression.)

In our published paper1 we have a series of tables that tells you how many visual fields you need to do to measure different rates of change. The ophthalmologist can apply these paradigms to detect these different rates of change.

Our study does have some limitations. For example, we used mean deviation as the key value, and we’re well aware that this is an imperfect metric. If a patient has a paracentral visual field loss at two or three points but the rest of the visual field is close to normal, changes in those few points would have a minimal impact on the mean deviation. Others factors such as the presence of a cataract or an inattentive patient can also affect the mean deviation. But it’s an index most of us are fairly comfortable using to describe the magnitude of visual field damage in a given patient, so we chose to use it in our statistical analysis.

The reality is, going from one visual field to two visual fields per year gives you a dramatic information gain. Going from two to three tests per year also gives you a significant information gain. Beyond that, the clinical value begins to taper off. So the ideal frequency should be between two and three visual fields per year, depending on how great a rate of progression you feel a given patient can tolerate without risking visual disability over the course of his or her lifetime.

Dealing with Clinical Obstacles

Not surprisingly, the first thing people say when I recommend six visual fields in the first two years, is: “I can’t possibly do that.” In response, I’d like to make several points:

• Doing six exams in the first two years isn’t a big change from what many ophthalmologists are already doing. If a glaucoma patient comes to you for the first time, you’d do one visual field, and you’d probably want to do another to establish a reasonable baseline. You might have to do a third one to rule out any potential learning effects. Then you might want to do a visual field every six months after that. You’re already approaching six visual fields in the first two years. If you’ve done five, the information you gain by adding a sixth visual field, statistically speaking, is tremendous—enough to ensure that you’ll detect a rate of visual field loss of 2 dB per year.

• Although reimbursement currently will not cover this many visual fields in some practices, this can be used as a powerful argument for getting those kinds of limitations changed. Many ophthalmologists tell me that they can’t get reimbursed for more than one, or perhaps two, visual fields per year. I would argue that fighting to get this changed is a worthy cause.

Consider the economics involved: In our province in Canada, we’re reimbursed about $50 for doing a visual field. We have an estimated 300,000 potential glaucoma patients; doing six visual fields instead of five for these individuals would cost the health-care system about $15 million total. Spending $15 million to create a dramatic improvement in our ability to figure out which patients are going to end up with visual disability, allowing us to tailor treatment in those patients to prevent that outcome, is a small investment for a potentially great health-care cost saving—the cost of rehabilitating patients with severe visual field loss—in the long run. (Consider the amount being spent to cover the cost of recently developed treatments for macular degeneration.) So not doing this is a false economy.

• Not every patient needs the additional visual fields. I’m not suggesting that we need to do this many visual fields on every patient. Again, whether a patient needs to be checked for fast progression can be decided based upon a group of factors, including age and initial condition. And this wouldn’t apply to ocular hypertensives. Furthermore, fast progressers probably only constitute about 20 percent of the glaucoma population—maybe even less—and those patients are the only ones you might want to test more frequently.

Ensuring Usable Test Results

Clearly, the clinical value of any number of visual field tests depends on having good quality data. I would offer these suggestions to help maintain the reliability of test results:

• Make sure you and your staff realize the value of visual field data. Sometimes the staff— perhaps even the ophthalmologist— may not fully appreciate that the perimetry examination provides crucial information about the patient’s disease status and progression. The other tests that we do—measuring eye pressure, looking at the optic disc, looking at the nerve fiber layer—relate to the disease process, but they don’t measure the functional consequences of the disease. A plethora of studies tell us that patients’ ability to function well—how many times they fall, how many car crashes they have, how many hip fractures they have—are all related to visual field damage. If everyone on the staff appreciates this fact, testing will be done more carefully, and even the patient will pick up on the fact that the visual field exam is important. (Ultimately, of course, this attitude has to start with the ophthalmologist.)

• Mitigate patient fears. While it’s important for patients to understand the value of the visual field test, you don’t want them to see it as a daunting task. For example, patients often get anxious because they’re not seeing the stimulus, and that can reduce the quality of the examination. It’s important for the technician to tell the patient that about 50 percent of the time he won’t see the stimulus—that’s intentional. It’s also important to let the patient know that the technician will be there during the test; that the patient can stop the test at any time to take a break or ask questions; if her eyes get dry, she can have a moisturizing eye drop. This reduces patient anxiety, and it can make a huge difference in how reliable the test information is. If it takes an extra minute of the technician’s time at the beginning of the exam to reinforce these things, our experience has been that the extra minute is very worthwhile. You’ll have far fewer unreliable examinations.

• Standardize the instructions. It’s important that every patient receives the same instructions. Having standardized instructions ensures that every patient gets all the information necessary to take the test properly and with minimum anxiety. (These instructions should include the statements mentioned in the previous point.) Obviously, if a patient has taken the visual field test for several years and you know he produces reliable results, you don’t need to repeat the instructions every time.

• Be careful about eliminating test data on the grounds of a learning effect. I don’t advocate eliminating visual fields from your data automatically on the grounds of a possible learning effect. (Learning effects usually occur when there’s an unexplainable improvement in the visual field.) It’s true that most patients learn between the first and second examination, but that’s not always the case. The removal of a visual field from the analysis is a judgment call and can usually be made when there are additional visual fields, which may indicate the truer nature of the visual field loss.

• Don’t perform alternate types of visual field exams at the expense of

standard ones. Ophthalmologists currently have access to a number of

alternate visual field testing strategies and instruments. I see these

tests as primarily valuable in a research environment today, but I’m

concerned that some clinicians may choose to perform them at the cost of

doing fewer standard automated perimetry exams. Again, a greater

number of standard exams translates to a greater ability to catch

progression at rates that are dangerous in the long run but difficult to

measure with only a handful of visual fields. In some situations,

using alternate perimetric tests may be necessary, but I would urge

clinicians to be conscious of the potential trade-off.

• To ensure data quality, don’t just depend on reliability indices. These can be useful, but we encourage ophthalmologists not to trust them automatically. They’re meant to be a guideline. For example, it’s possible to have high fixation losses in a patient who is doing the test perfectly well. There are also scenarios in which the fixation error may appear within acceptable limits from the perimeter’s standpoint, but a technician supervising the test might feel otherwise.

For that reason, I’d encourage ophthalmologists to get the technician to write down subjectively whether or not the patient did the test well. Was the patient attentive? Falling asleep? Particularly anxious that day? All of these things will give you an idea of how reliable the test is. Sometimes this kind of observation corroborates what the perimeter is reporting, but often it doesn’t.

The important thing is to not assume test data is good or bad just because the instrument says so. Dropping a legitimate result or including a suspicious one may undercut your ability to catch progression.

• Don’t mix the results of different test strategies. For example, you shouldn’t mix a SITA-standard strategy with a SITA-fast strategy, or a 10-2 strategy with a 24-2 strategy. If you have a Humphrey perimeter, we recommend using the SITA-standard strategy for all testing. The time savings you get going from SITA-standard to SITA-fast is not that significant, but the information loss is.

Taking the Next Step

The work we reported in our published paper on this topic is just a beginning. Our intention is to eventually generate concrete guidelines for visual field testing that clinicians can use, based on each patient’s baseline criteria. Eventually we’d like to create user-friendly software that works in conjunction with perimeters to aid in analysis of the data and projection of likely future progression. Of course, we also hope to aid in the process of getting insurers to see the preventive value of doing more visual fields for some patients, so that those visual fiields are routinely reimbursed.

At the end of the day, we want to make sure that the clinician gathers the most effective amount of useful data and uses that data sensibly to make clinical decisions. If we’re successful, this should have a significant impact on our ability to prevent glaucoma from leading to visual disability.

The reality is that the accuracy of any decision you make regarding progression in a patient will be directly proportional to the amount of data you have. If you have five years worth of data and you’ve got two to three good-quality visual fields per year, you’ve got a pretty good idea of what’s happening to that patient. If you’ve done three tests over a period of five years, you may not have any idea what’s going on.

How Many Visual Fields?

Given these concerns, we wanted to provide some practical guidelines regarding the number of visual field exams that are necessary to accurately detect a given rate of progression. So, we did a series of analyses to come up with the number of examinations that would be required to detect different levels of progression.

What our statistical analyses found is that six visual field exams have to be performed during the first two years in order to detect a rate of progression of about 2 dB per year—sufficient to threaten a patient’s vision over time, but not easily determined with a smaller number of exams during the same amount of time. Again, a really fast rate of progression can be measured with fewer tests; but a rate of 2 dB per year (or slower) cannot reliably be determined without doing six tests in two years’ time.

For example, suppose a new glaucoma patient comes to see you. The first visual field you perform will give you a pretty good idea of whether the visual field is damaged. That visual field should be repeated to ensure the accuracy of your baseline. If those two exams indicate the presence of damage, then it becomes important To determine whether or not the individual is a fast progresser. (This is true even if you begin treatment to lower the intraocular pressure; some individuals will continue to progress quickly despite being treated.) If that patient is then followed with a total of six visual fields over the two years, the ophthalmologist can get a good idea of how fast that patient is progressing. Once that rate of change has been determined, the need for more serious treatment and monitoring can be decided in light of the patient’s visual field damage-vs.-age plot. (Note: Commercially available software such as the Humphrey Progression Analysis system can work well for the analysis; the issue is having a sufficient number of visual field tests for the analysis to pick up the progression.)

In our published paper1 we have a series of tables that tells you how many visual fields you need to do to measure different rates of change. The ophthalmologist can apply these paradigms to detect these different rates of change.

Our study does have some limitations. For example, we used mean deviation as the key value, and we’re well aware that this is an imperfect metric. If a patient has a paracentral visual field loss at two or three points but the rest of the visual field is close to normal, changes in those few points would have a minimal impact on the mean deviation. Others factors such as the presence of a cataract or an inattentive patient can also affect the mean deviation. But it’s an index most of us are fairly comfortable using to describe the magnitude of visual field damage in a given patient, so we chose to use it in our statistical analysis.

The reality is, going from one visual field to two visual fields per year gives you a dramatic information gain. Going from two to three tests per year also gives you a significant information gain. Beyond that, the clinical value begins to taper off. So the ideal frequency should be between two and three visual fields per year, depending on how great a rate of progression you feel a given patient can tolerate without risking visual disability over the course of his or her lifetime.

Dealing with Clinical Obstacles

Not surprisingly, the first thing people say when I recommend six visual fields in the first two years, is: “I can’t possibly do that.” In response, I’d like to make several points:

• Doing six exams in the first two years isn’t a big change from what many ophthalmologists are already doing. If a glaucoma patient comes to you for the first time, you’d do one visual field, and you’d probably want to do another to establish a reasonable baseline. You might have to do a third one to rule out any potential learning effects. Then you might want to do a visual field every six months after that. You’re already approaching six visual fields in the first two years. If you’ve done five, the information you gain by adding a sixth visual field, statistically speaking, is tremendous—enough to ensure that you’ll detect a rate of visual field loss of 2 dB per year.

• Although reimbursement currently will not cover this many visual fields in some practices, this can be used as a powerful argument for getting those kinds of limitations changed. Many ophthalmologists tell me that they can’t get reimbursed for more than one, or perhaps two, visual fields per year. I would argue that fighting to get this changed is a worthy cause.

Consider the economics involved: In our province in Canada, we’re reimbursed about $50 for doing a visual field. We have an estimated 300,000 potential glaucoma patients; doing six visual fields instead of five for these individuals would cost the health-care system about $15 million total. Spending $15 million to create a dramatic improvement in our ability to figure out which patients are going to end up with visual disability, allowing us to tailor treatment in those patients to prevent that outcome, is a small investment for a potentially great health-care cost saving—the cost of rehabilitating patients with severe visual field loss—in the long run. (Consider the amount being spent to cover the cost of recently developed treatments for macular degeneration.) So not doing this is a false economy.

• Not every patient needs the additional visual fields. I’m not suggesting that we need to do this many visual fields on every patient. Again, whether a patient needs to be checked for fast progression can be decided based upon a group of factors, including age and initial condition. And this wouldn’t apply to ocular hypertensives. Furthermore, fast progressers probably only constitute about 20 percent of the glaucoma population—maybe even less—and those patients are the only ones you might want to test more frequently.

Ensuring Usable Test Results

Clearly, the clinical value of any number of visual field tests depends on having good quality data. I would offer these suggestions to help maintain the reliability of test results:

• Make sure you and your staff realize the value of visual field data. Sometimes the staff— perhaps even the ophthalmologist— may not fully appreciate that the perimetry examination provides crucial information about the patient’s disease status and progression. The other tests that we do—measuring eye pressure, looking at the optic disc, looking at the nerve fiber layer—relate to the disease process, but they don’t measure the functional consequences of the disease. A plethora of studies tell us that patients’ ability to function well—how many times they fall, how many car crashes they have, how many hip fractures they have—are all related to visual field damage. If everyone on the staff appreciates this fact, testing will be done more carefully, and even the patient will pick up on the fact that the visual field exam is important. (Ultimately, of course, this attitude has to start with the ophthalmologist.)

• Mitigate patient fears. While it’s important for patients to understand the value of the visual field test, you don’t want them to see it as a daunting task. For example, patients often get anxious because they’re not seeing the stimulus, and that can reduce the quality of the examination. It’s important for the technician to tell the patient that about 50 percent of the time he won’t see the stimulus—that’s intentional. It’s also important to let the patient know that the technician will be there during the test; that the patient can stop the test at any time to take a break or ask questions; if her eyes get dry, she can have a moisturizing eye drop. This reduces patient anxiety, and it can make a huge difference in how reliable the test information is. If it takes an extra minute of the technician’s time at the beginning of the exam to reinforce these things, our experience has been that the extra minute is very worthwhile. You’ll have far fewer unreliable examinations.

• Standardize the instructions. It’s important that every patient receives the same instructions. Having standardized instructions ensures that every patient gets all the information necessary to take the test properly and with minimum anxiety. (These instructions should include the statements mentioned in the previous point.) Obviously, if a patient has taken the visual field test for several years and you know he produces reliable results, you don’t need to repeat the instructions every time.

• Be careful about eliminating test data on the grounds of a learning effect. I don’t advocate eliminating visual fields from your data automatically on the grounds of a possible learning effect. (Learning effects usually occur when there’s an unexplainable improvement in the visual field.) It’s true that most patients learn between the first and second examination, but that’s not always the case. The removal of a visual field from the analysis is a judgment call and can usually be made when there are additional visual fields, which may indicate the truer nature of the visual field loss.

|

• To ensure data quality, don’t just depend on reliability indices. These can be useful, but we encourage ophthalmologists not to trust them automatically. They’re meant to be a guideline. For example, it’s possible to have high fixation losses in a patient who is doing the test perfectly well. There are also scenarios in which the fixation error may appear within acceptable limits from the perimeter’s standpoint, but a technician supervising the test might feel otherwise.

For that reason, I’d encourage ophthalmologists to get the technician to write down subjectively whether or not the patient did the test well. Was the patient attentive? Falling asleep? Particularly anxious that day? All of these things will give you an idea of how reliable the test is. Sometimes this kind of observation corroborates what the perimeter is reporting, but often it doesn’t.

The important thing is to not assume test data is good or bad just because the instrument says so. Dropping a legitimate result or including a suspicious one may undercut your ability to catch progression.

• Don’t mix the results of different test strategies. For example, you shouldn’t mix a SITA-standard strategy with a SITA-fast strategy, or a 10-2 strategy with a 24-2 strategy. If you have a Humphrey perimeter, we recommend using the SITA-standard strategy for all testing. The time savings you get going from SITA-standard to SITA-fast is not that significant, but the information loss is.

Taking the Next Step

The work we reported in our published paper on this topic is just a beginning. Our intention is to eventually generate concrete guidelines for visual field testing that clinicians can use, based on each patient’s baseline criteria. Eventually we’d like to create user-friendly software that works in conjunction with perimeters to aid in analysis of the data and projection of likely future progression. Of course, we also hope to aid in the process of getting insurers to see the preventive value of doing more visual fields for some patients, so that those visual fiields are routinely reimbursed.

At the end of the day, we want to make sure that the clinician gathers the most effective amount of useful data and uses that data sensibly to make clinical decisions. If we’re successful, this should have a significant impact on our ability to prevent glaucoma from leading to visual disability.

Dr. Chauhan is a professor, research director and chair in vision research at the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Dalhousie University in Halifax. He leads the Canadian Glaucoma Study, the largest clinical study of glaucoma conducted in Canada.

1. Chauhan BC, Garway-Heath DF, Goñi FJ, Rossetti L, Bengtsson B, Viswanathan AC, Heijl A. Practical recommendations for measuring rates of visual field change in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2008;92:4:569-73.