Why I Combine the Surgeries

Robert Fechtner, MD

Newark, N.J.

I perform combined cataract and glaucoma surgery. My goals for this procedure differ depending on the clinical situation. All patients must have a visually significant cataract with a reasonable expectation that vision will improve or there must be a need for better visualization of the posterior pole.

In some patients, I wish to achieve lower intraocular pressure than has been achieved with medications and laser trabeculoplasty. Other patients' IOPs are at the target level, but require more than two medications to achieve that goal. In some there is a prior trabeculectomy with borderline function. My goal is to create a relatively watertight wound at the completion of the surgery with the ability to titrate resistance to outflow with laser suture lysis or releasable sutures.

Technique

My current technique uses a single site with a small limbal peritomy, a short scleral tunnel 3-mm wide, phacoemulsification and a foldable intraocular lens. After successful completion of the cataract procedure, I fill the anterior chamber with viscoelastic and apply mitomycin-C on a cut surgical sponge with a wide area of exposure. After I remove the sponge and irrigate the eye, I create a sclerostomy with a punch, remove the viscoelastic and suture the wound with a relatively tight closure to limit the amount of flow. This anticipates laser suture lysis to increase flow post-operatively once the conjunctival wound has sealed.

|

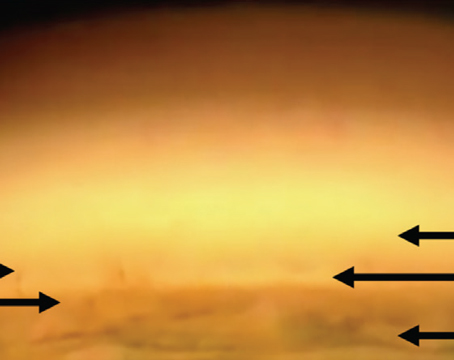

| Stretching. It is crucial to achieve adequate capsular exposure. Small pupil surgery is challenging and can lead to complications. Often, the use of viscoelastic and Kuglen hooks can stretch the pupil sufficiently. |

I do not view combined surgery as my best IOP-lowering operation, but I do believe that it offers advantages over the alternatives. It allows me to lower the IOP at the time of cataract surgery for those not satisfactorily controlled. For other patients, I can reduce or eliminate their dependence on medication for IOP control.

|

| Phaco. I make a curved incision that approaches the limbus centrally, and a scleral tunnel. This wound tends to be astigmatism neutral despite the sclerostomy. I use standard phacoemulsification techniques. |

Controlled, on Multiple Medications

When I consider surgery for patients whose pressure is well-controlled but on multiple medications I tell them: "We have been able to control your IOP with medications, but it requires several medications to reach the target IOP. And you have now developed a cataract that affects your vision and interferes with your activities. We have a couple of options. We can just do cataract surgery alone. I expect that will improve your vision, but you will still likely need medications to control your pressure. We can combine glaucoma surgery with your cataract operation. It is a little more work for the surgeon but will not decrease the chances for a successful cataract operation, and there is a 50/50 chance it will control your pressure well enough so that we can decrease or eliminate your glaucoma medications."

Not Well-controlled

Punch. With a Kelley Descemet punch, a sclerostomy is created at the center of the wound. Do not punch all the way to the posterior lip of the wound but leave a small overlap to create some resistance when the wound is sutured.

When considering surgery for patients who are not well-controlled I say: "We have been unable to control your intraocular pressure well enough with medications (or laser). I recommend surgery to lower your IOP. You also have a cataract that is interfering with your vision and activities. We have options. We can just do the glaucoma operation which has about an 85 percent chance of success. But this guarantees that you will need a second operation to remove your cataract. We can do both operations at the same time and there is a 50/50 chance you will need only one operation. If the glaucoma operation does not work the first time, we can go back and do the second operation."

A trabeculectomy is more often successful when not performed with a cataract extraction. Lower IOPs are more often achieved with trabeculectomy alone.

Not every patient is a candidate for combined surgery. When a patient has advanced glaucoma, uncontrolled intraocular pressure or needs a very low IOP I favor trabeculectomy. For the many patients who do not fall in these categories, combined surgery offers the benefits of visual rehabilitation, decreased dependence on IOP lowering medicines, lower IOP and a single surgical procedure to address two problems. The visual outcome of the cataract surgery is the same. It is also possible that the trabeculectomy will be successful.

|

| Closure. A single 10-0 nylon suture can be used to close the wound, then test for flow. Flow should be minimal. If it is too brisk, add an additional 10-0 nylon on each side. Once the conjunctiva has sealed (usually four to seven days) begin planned suture lysis to "turn on" the sclerostomy. |

Assuming the success estimates are correct, this means I am trading a 35- percent success rate for 50-percent chance of one operation instead of two. For the patient who avoids the second operation, the benefits are clear. For the patient who requires a second operation anyway, the downside is that there is now only one untouched quadrant for future glaucoma surgery instead of two. This factor, I believe, favors combined surgery for many of my glaucoma patients who need cataract surgery.

Dr. Fechtner is a professor at the New Jersey University of Medicine and Dentistry.

Why I Separate the Surgeries

Anthony Realini, MD

Little Rock, Ark.

Commonly, cataract and glaucoma coexist. Both are associated with an aging population and glaucoma management often causes cataracts. The question is, does the co-existence of both cataract and glaucoma in the same eye mean that simultaneously operating for both conditions is a good idea?

I say no, and here's why. Eyes that are candidates for a combined procedure of cataract extraction and trabeculectomy must meet the indications for both procedures: visually significant cataract and glaucoma uncontrolled on reasonable medical therapy. In many eyes undergoing combined procedures, however, these co-indications are not met.

Often, a patient needing a trabeculectomy and possessing a cataractous lens will be subjected to a combined procedure even in the absence of any visual complaints related to the cataract. Similarly, patients with visually significant cataracts and glaucoma controlled on two or three medications will often be subjected to combined procedures in an effort to reduce the burden of chronic glaucoma medication therapy. But in both cases, patients undergo additional surgery and take on more risks.

|

| A filtering bleb one week following primary trabeculectomy. |

In my experience, the need for cataract surgery and glaucoma surgery rarely arises simultaneously. Rather, one or the other becomes necessary while the other isn't imperative but could be dealt with conveniently at the same time, and the astute surgeon recognizes the opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. Even in eyes with indications for both procedures, I believe that combining the two operations might jeopardize outcomes.

I have concerns regarding outcomes. First, if visually significant cataract is driving the decision to operate, it is very possible that the "extra" surgery of trabeculectomy could undermine visual recovery by increasing the risk of inflammation, cystoid macular edema, and surgically induced astigmatism (not to mention the rare but disastrous outcomes such as hypotony maculopathy and blebitis/endophthalmitis).

Second, if uncontrolled glaucoma is driving the decision to operate, the "extra" surgery of cataract extraction could easily stir up enough additional inflammation that it could compromise the new bleb. In both cases, by doing more rather than enough, the surgeon potentially shoots him- or herself (not to mention the patient) in the foot.

I much prefer to separate the two procedures so the trauma to the eye from the two surgeries is consecutive rather than concurrent.

Ideally, cataract extraction comes first, through a clear corneal incision to spare the conjunctiva. After four to six weeks, when the inflammation has cleared, I perform trabeculectomy. Occasionally high IOP requires that trabeculectomy be performed first. When the cataract is removed in these and any eyes with a functioning filter undergoing cataract surgery, regardless of the temporal proximity of the cases, I treat the eye with frequent topical steroids and occasionally a short course of oral steroids to minimize inflammation that might compromise the filter.

Some surgeons argue that simultaneous cataract and glaucoma surgery minimizes the risk of a postoperative IOP spike. I agree that performing cataract surgery alone in a glaucomatous eye does not protect against this spike. But I don't think that prophylactically performing additional surgery is an appropriate way to prevent a potential cataract surgery complication.

In eyes with advanced glaucoma undergoing cataract surgery, an oral dose of a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor immediately postop, and another dose at bedtime the day of surgery can reduce or eliminate the pressure spike less invasively than by adding trabeculectomy.

Some surgeons point out that performing cataract surgery after trabeculectomy increases the risk

of late bleb faiure. In my experience, once a trabeculectomy establishes itself and a functioning fistula has formed, performing cataract surgery through a clear cornea wound is unlikely to jeopardize bleb function. This potential risk is lessened in an established bleb compared to a fresh bleb, which again makes the argument for separating the procedures in time.

I believe that combined cataract and uncontrolled glaucoma requires two separate operations. Since these patients have two separate diseases, I think this is an appropriate treatment.

Dr. Realini is an assistant professor and director of glaucoma services at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Editor's Comment

Peter A. Netland, MD, PhD

Memphis, Tenn.

Coexisting cataract and glaucoma is a common clinical problem. The management of this problem varies widely when different clinicians compare their techniques. The opinions expressed by Drs. Realini and Fechtner are quite different, but both are within the scope of standard clinical practice.

Most clinicians would agree that cataract surgery is indicated when there is a decrease in visual acuity due to lens opacity causing limitation of function in daily activities, the opacity precludes diagnosis and treatment of other eye disease, or there are actual or impending complications of lens-induced ocular disease. Filtration surgery may be combined with cataract surgery when glaucoma is not well-controlled with medications, there is a history of borderline or difficult glaucoma, and there is advanced cupping or visual loss. The number of medications to represent "borderline or difficult glaucoma" varies, with many clinicians choosing two to three medications as their indication for combined surgery.

Whether we need to combine the procedures at one setting or separate the procedures over time is not well-understood. Whether we should perform the surgery at one site or at two different sites is also not clear.

Perhaps the reason for the lack of consensus is that the literature provides conflicting and incomplete information. Studies of combined procedures are difficult to perform well. A recent evidence-based review was able to conclude that the evidence is strong for better long-term control of IOP with combined glaucoma and cataract operations compared with cataract surgery alone.1 For other strategies for cataract and glaucoma, the available information was insufficient to draw solid conclusions.

For the time being, we have divergent opinions expressed by different clinicians about the choice between performing cataract and glaucoma surgery at the same time or at two separate times. The individual clinicians treating these patients should be familiar with these different strategies and choose what works best in their hands, and what is best in their judgment for the individual patient.

Dr. Netland is the Siegal Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Tennessee, Memphis.

1. Friedman DS, Jampel HD, Lubomski LH, et al. Surgical strategies for coexisting glaucoma and cataract. An evidence-based update. Ophthalmology 2002; 109:1902-1915.