NEOVASCULAR GLAUCOMA IS THE MOST COMMON TYPE OF glaucoma associated with retinal disease. Because it can lead to complete loss of vision or even the need for enucleation, early diagnosis and immediate treatment are imperative.

Here, I'd like to share some of what I've learned during my experience managing this disease.

Several ocular and systemic diseases predispose patients to retinal hypoxia and ischemia, leading to subsequent release of angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). (For a list of some of the most common predisposing disease conditions, see Table 1, below.) These cause neovascularization of the retina, iris and/or angle, and the subsequent formation of fibrovascular membranes, resulting in neovascular glaucoma.

| Table 1. Common Predisposing Factors |

| • Diabetes |

| • Central retinal vein occlusion |

| • Ocular ischemic syndrome/carotid occlusive disease |

| • Central retinal artery occlusion |

| • Retinal detachment |

| • Sickle cell retinopathy |

| • Chronic uveitis |

| • Ocular tumors (choroid melanoma, retinoblastoma, large cell lymphoma) |

| • Radiation retinopathy |

Managing the Disease

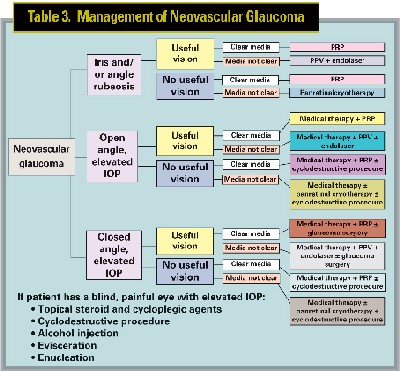

Neovascular glaucoma normally progresses through three stages: iris and/or angle rubeosis (pre-glaucoma); secondary open-angle glaucoma; and closed-angle glaucoma. (See Table 2, below). Be sure to examine the patient carefully to correctly evaluate the stage of the disease. Also, take a careful history so you can identify the underlying cause. If intraocular pressure is elevated, you'll need to treat both the elevated IOP and the cause.

| Table 2. Stages of Neovascular Glaucoma |

| Symptoms and signs of neovascular glaucoma include decreased vision, photophobia, corneal edema, conjunctival injection, rubeosis, elevated intraocular pressure, inflammation, hyphema and vitreous hemorrhage. If the elevation in IOP is acute, the patient may exhibit severe pain, headache, nausea and/or vomiting. |

| Stage 1: (pre-glaucoma): Iris and or angle rubeosis. At this stage tufts of rubeosis can be found at the pupillary margin and/or rubeotic vessels may be found in the angle. IOP is normal. |

| Stage 2: Open-angle glaucoma. At this point in the disease, the growth of fibrovascular tissue, including rubeotic vessels over the trabecular meshwork, decreases aqueous outflow and increases IOP in an aberrantly open angle. (See photograph, page 86.) The rubeosis iridis is typically more florid with some inflammatory component and possible hyphema. |

| Stage 3: Closed-angle glaucoma. The fibrovascular membrane proliferates and contracts, causing progressive angle closure, ectropion uveae and a flat, glistening appearance to the iris. Rubeosis is severe, with possible hyphema, some inflammation and IOP as high as 60 to 70 mmHg. |

• Stage 1: If the patient has iris and/or angle rubeosis, but IOP is normal, note the clarity of the media. If the media are clear, panretinal photocoagulation is recommended; if the media are cloudy because of vitreous hemorrhage, a pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser treatment are likely to be most effective. If the media are cloudy because of visually significant cataract, consider cataract extraction and immediate panretinal photocoagulation to prevent further worsening of the neovascularization, which can progress rapidly after cataract extraction.

• Stage 2: If the angle is open and the eye still has useful vision, but IOP is above normal, initiate medical therapy to reduce aqueous production. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (topical or systemic), topical beta-blockers and/or alpha-2 agonists are appropriate; prostaglandin analogs are rarely effective because of compromised access to the uveoscleral route. (There is also a theoretical concern regarding exacerbation of inflammation with drugs that may disrupt the blood-aqueous barrier.) In addition, anti-inflammatory agents such as topical steroid drops and cycloplegic agents may be indicated.

|

| Rubeotic vessels over the trabecular meshwork eventually cause decreased aqueous outflow and increased IOP. |

The retinal neovascularization should be addressed as soon as possible to prevent further neovascularization of the angle and formation of peripheral anterior synechiae. If the media are clear you should perform panretinal photocoagulation; if the vitreous isn't clear because of hemorrhage, perform a pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser. If the eye has a visually significant cataract, consider cataract extraction and immediate panretinal photocoagulation. If you find both cataract and vitreous hemorrhage, consider cataract extraction, pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser.

If the eye has no useful visual potential, initiate medical therapy to control IOP, including cycloplegic agents, steroid drops for comfort and panretinal photocoagulation if the media are clear. If the media are cloudy, perform panretinal cryotherapy. If IOP can't be controlled medically, consider a cyclodestructive procedure.

• Stage 3: If the eye still has useful vision, panretinal photocoagulation is the treatment of choice for the underlying retinal problem, assuming the media are clear. As above, if you find vitreous hemorrhage, a pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser are recommended. If the eye has a visually significant cataract, consider cataract extraction and immediate panretinal photocoagulation. If you find both cataract and vitreous hemorrhage, consider cataract extraction, pars plana vitrectomy and endolaser.

Treatment of the elevated IOP should be chosen based on the degree of angle closure. Initial medical therapy should include cycloplegic agents and steroid drops. If this isn't sufficient to control IOP in the acute phase or even after the regression of the rubeosis, because of peripheral anterior synechiae, surgical intervention such as a glaucoma drainage implant or trabeculectomy with antimetabolites may be indicated. This can be done at the time of retinal surgery, if retinal surgery is indicated.

If the eye no longer has useful visual potential, initiate medical therapy to control IOP, including cycloplegic agents, steroid drops for comfort and panretinal photocoagulation if the media are clear. If the media are cloudy, perform panretinal cryotherapy and cyclodestructive surgery to control IOP. However, if the eye has no vision and medical therapy isn't controlling the pain and discomfort, take more extensive action, such as performing retrobulbar alcohol injection, evisceration, or enucleation.

As you can see, managing patients with neovascular glaucoma requires an individualized case approach; each situation requires a different response in order to minimize further vision loss. Even under the best circumstances, the diagnosis of neovascular glaucoma carries a guarded prognosis, and success is highly dependent on prevention and early treatment. However, if we remain alert for signs and symptoms, as well as the factors that predispose patients to this problem, we stand a good chance of catching the disease early and preserving the patient's vision.

Dr. Al-Aswad is assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Edward S. Harkness Eye Institute.