Presentation

An otherwise healthy 31-year-old female of Irish descent presented to the Oculoplastics Service with a one-month history of chronic irritation and redness along the eyelid margins of both eyes. She denied any sharp pain, edema, induration, scarring, alopecia, eye pain or vision changes. She noted a four-month history of intermittent eruptions of 3-to-5 mm erythematous sores on her upper eyelids and forehead and pustules on her nose. The eyelid lesions were treated by her primary-care physician with a steroid cream.

The lesions remitted with the cream, however, they returned when she stopped its application. She arrived in consultation for a second opinion.

Medical History

The patient's history was notable for obtaining a new kitten shortly before the onset of her symptoms, and she recalled being scratched by the kitten on her face in the area of the sores. Her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. She denied any history of other rashes, joint pain or arthritis. She had no history of malignancies, prolonged sun exposure, fever blisters or cold sores. She denied any new skin creams, makeup, soaps, detergents or perfumes. She had no allergies and was on no medications other than the steroid creams prescribed by her general practitioner.

Examination

On examination she had 20/20 uncorrected vision in both eyes. Pupils and motility were normal. Slit-lamp examination was unremarkable. External exam of her face and lids demonstrated fair skin with several excoriated erosions on her forehead and right upper eyelid. She had an inflamed ulcerative blepharitis of her lower lid margins and meibomian gland inspissation and inflammation of all four eyelids. She had no regional adenopathy.

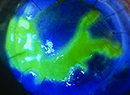

She did have several pustules on her nose as well (See Figure 1).

Diagnosis, Management and Treatment

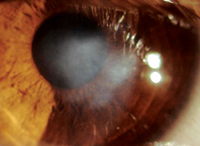

Given her complexion, heritage and exam findings, the patient was diagnosed with roseacea and placed on a regimen of lid scrubs, tobramycin/dexamethasone ointment b.i.d., doxycycline 100 mg b.i.d. by mouth, and metronidazole gel to her face. These remedies provided only minimal relief (See Figure 2).

She returned one month later noting some improvement of her blepharitis along the eyelid margins. However, she remarked that the small erythematous plaques on her upper eyelid and forehead remained unchanged. She was seen by her primary-care physician who felt these lesions may have represented cutaneous fungal infections. The patient was placed on ketoconazole and clotrimazole creams, with no change after one week.

At this point, the patient returned to the oculoplastics clinic where a tissue culture was obtained from the upper eyelid plaque and a punch biopsy from the forehead plaque. The tissue culture was negative for fungus. The punch biopsy was positive for a lichenoid dermatitis with a dense perivascular and periadnexal mononuclear cellular infiltrate and increased interstitial mucin deposition (See Figures 3a & 3b). The findings were diagnostic of lupus. A systemic workup was negative. She was therefore diagnosed with discoid lupus, and was placed on a short course of oral steroids followed by oral dapsone. Her lesions gradually and completely resolved. No further active disease was reported at four months after resolution. She did, however, develop some mild skin atrophy in the area of the lesions (See Figure 4).

Discussion

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease, with a worldwide prevalence of 17 to 48 per 100,000 of population.1 In general, females are more frequently affected than males. With far-reaching systemic manifestations, SLE routinely affects the skin, joints, kidneys, heart, nervous system, serosal surfaces and blood elements. Its diagnosis is a clinical one, but may be aided by histology and with positive autoantibody detection.2

Skin disease is one of the most frequent clinical complaints of patients suffering from SLE, and has been found to occur in up to 70 percent of patients during the course of the disease. This may manifest as alopecia or a malar rash. However, cutaneous lupus may be found in the absence of systemic disease.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus is diagnosed by serology and histology as a cutaneous autoimmune reaction and is thought to be in a clinical and histologic spectrum with SLE.3 CLE is further subclassified into three main forms: chronic CLE, subacute CLE and acute CLE. Each subtype has a unique prevalence, histology, clinical course, potential for development of SLE and other autoimmune diseases and favored treatment modalities. Chronic CLE, for example, is at least twice as prevalent as SLE but with a less severe clinical course.3

Discoid lupus erythematosus, a chronic cutaneous dermatitis, is an additional subtype of CLE. Serologically, patients with DLE have a lower tendency to be positive for SLE-associated autoantibodies, but 20 percent of patients with generalized DLE and 5 percent with localized DLE go on to develop SLE. It typically occurs in patients 20 to 40 years of age. The head and neck are involved in 80 percent of cases.1,3,4 Clinically, DLE lesions begin as erythematous patches that then scale, become hyperkeratotic and atrophy with concomitant pigmentary changes. These changes are often associated with pruritis.1

While lesions on the face, scalp, neck and trunk may have these fairly characteristic appearances, eyelid lesions are much less common and can be clinically indistinct.1,4

As a result, nondescript DLE lesions of the eyelids can be a difficult clinical diagnosis. These are usually bilateral in presentation, and begin with erythema and edema of the lower eyelids.5 As a result, they are oftentimes initially misdiagnosed and mistreated as blepharitis.6 Chronic symptoms unresolved by standard blepharitis remedies coupled with scarring, scaling, and madarosis may raise suspicion of another disease process and broaden the differential to include sebaceous, squamous and basal cell carcinomas.

Lymphoma, eczema, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen planus, tinea faciei, drug reactions and sarcoidosis are appropriately considered on this differential, as well.1,7 In our case, the history of cat scratches was simply an outlier. The diagnosis is often made on serologic testing and tissue biopsy with full-thickness biopsy usually warranted only if a partial-thickness biopsy is not diagnostic.7,8

The treatment of DLE is aimed at both halting disease progression as well as limiting symptoms. Steroid creams are first-line therapy, although their failure in the treatment of blepharitis may prompt the eventual diagnosis of DLE itself. Corticosteroid injections may also be tried. Ultraviolet light protection can protect discoid lesions, and various types of lasers have been applied to localized lesions. However, antimalarial medications are typically the mainstay of treatment. Hydroxychloroquine treatment has been proven effective, but close clinical observation must be employed to monitor its known ocular side effects. If antimalarials become either too caustic or ineffective, immunosuppressive agents in the form of dapsone, azathioprine, methotrexate, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, retinoids and interferon alphas have been shown to be effective.1,3

Our patient responded well to a short course of topical and oral steroids with a dapsone taper, and her symptoms have remained in remission for four months on low-dose dapsone maintenance therapy.

Dr. Rabinowitz thanks Scott M. Goldstein, MD, of the Wills Oculoplastic Surgery service, and M. Barry Randall, MD, of the Pathology service at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, for their contributions and assistance with this case.

1. Acharya N, Pineda R, Uy H, Foster S. Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Masquerading as Chronic Blepharoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 2005;112:e19–e23.

2. Ardoin SP, Pisetsky DS. Developments in the scientific understanding of lupus. Arthritis Res Ther 2008;10(5):218.

3. Patel P, Werth V. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: A review. Dermatol Clin 2002 Jul;20(3):373-85

4. Leon Au. Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Presenting as Unilateral Blepharitis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr 2006;22(3):218-219.

5. Ena P, Pinna A, Carta F. Discoid lupus erythematosus of the eyelids associated with staphylococcal blepharitis and Meibomian gland dysfunction. Clin Exp Dermatol 2006;31(1):77-9.

6. Ricotti C, Tozman E, Fernandez A, Nousari, C. Unilateral Eyelid Discoid Lupus Erythematosus. Am J Dermatopathol 008;(30)5:512-513.

7. Gloor P, Kim M, McNiff JD, Wolfley D. Discoid lupus erythematosus presenting as asymmetric posterior blepharitis. Am J Ophthalmol 1997;124:707–9.

8. Frith P, Burge SM, Millard PF, Wojnarowska F. External ocular findings in lupus erythematosus: A clinical and immunopathological study. Br J Ophthalmol 1990;74;163-167.