Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drugs such as Avastin (bevacizumab) and Lucentis (ranibizumab) have become widely known for sparking a revolution in the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration. Now, case studies and early research are suggesting that these drugs may also play a part in treating glaucoma. Avastin has been found to be effective at treating neovascular glaucoma, not only causing apparent blood vessel regression but also lowering intraocular pressure in many severe cases.1-4 In addition, these drugs may have direct effects on fibroblasts, making them a potentially useful anti-fibrotic medication for use during many types of glaucoma surgery.

Reversing Neovascular Damage?

Neovascular glaucoma is typically a severe form of glaucoma most commonly associated with a chronic condition such as diabetic retinopathy or an acute condition such as central retinal vein occlusion. These conditions create ischemia in the retina, triggering excess VEGF production.

The excess VEGF can diffuse forward into the anterior chamber, leading to iris and angle neovascularization that eventually develops into a fibrovascular membrane; the membrane may grow over the iris and anterior chamber angle, ultimately blocking aqueous outflow. NVG may present with the angle anatomically open, covered with a membrane, or it may present as closed-angle glaucoma because of contraction of the membrane.

Treatment of NVG frequently involves surgery. Panretinal laser photocoagulation can be used to damage the cells producing the excess VEGF, leading to some regression of the new blood vessels in the iris and angle. However, in the majority of cases, the IOP remains elevated above normal and further glaucoma progression may occur.

In contrast, early reports of treatment using injections of Avastin or Lucentis find that the agents seem to have more of an effect than PRP.1-4 Surgeons have observed not only nonpatency or complete regression of the blood vessels, but a reduction in IOP, sometimes for an extended period. At this point it's only speculation, but it seems likely that the anti-VEGF drugs may cause regression of the neovascular membrane that blocks outflow in addition to reducing patency of the abnormal vessels. Future studies may provide insight into the exact reasons for IOP lowering following the injection of anti-VEGF agents, as compared to neovascular glaucoma patients who only receive PRP.

It's worth noting that these drugs don't lower IOP in every case of NVG. The mechanism behind failure of IOP lowering is probably linked to the stage of NVG. In the final stage of NVG, the angle is obliterated as a result of fibrovascular ingrowth and contraction of the drainage angle, making regression of vessels less effective for IOP control. This underscores the importance of recognizing NVG and treating prior to end-stage disease.

What the Data Shows

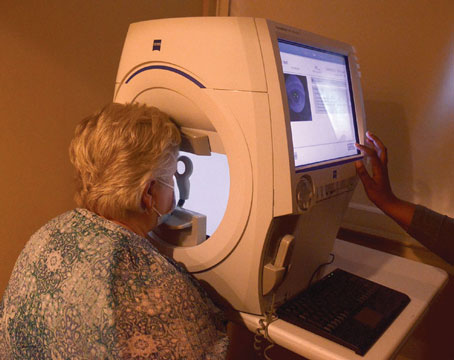

Currently, anti-VEGF drugs are not approved for treating ocular diseases other than macular degeneration. Despite this, off-label use of Avastin for neovascular glaucoma has been reported to be successful. Dr. Kahook and colleagues reported on the utility of intravitreal bevacizumab injection in a patient with neovascular glaucoma following CRVO.1 (See images below.) Bevacizumab (1 mg) was used after failed IOP control with transscleral cyclophotocoagulation and PRP. They noted improved IOP within two days of the injection and concluded bevacizumab may be an effective medication for the treatment of neovascular glaucoma. A 2008 study reported results of intracameral Avastin (1.25 mg) injections for iris neovascularization (NVI).4 Pressure was controlled in eight of nine eyes that had elevated pressure at the time of injection, thus reducing the need for glaucoma surgery.

In most reports so far, anti-VEGF drugs have been used as an adjunct to PRP, since that is still considered the standard treatment for neovascularization related to diabetic retinopathy and the ischemic form of CRVO. Nevertheless, use of PRP may be reduced in the future should anti-VEGF drugs turn out to be as effective—or more effective—than PRP. After all, PRP damages the retina in order to reduce production of VEGF. It doesn't do anything that directly repairs the damage or reverses the disease; it simply reduces the presence of VEGF while leading to permanent loss of peripheral vision. In contrast, drugs such as Avastin and Lucentis don't appear to injure the retina, and may actually lower IOP. (Of course, the pharmacologic effect of anti-VEGF drugs eventually wears off, while the effect of PRP is permanent.) Further clinical studies are under way to evaluate the utility of Avastin for iris neovascularization independent of PRP.

One downside of injecting anti-VEGF drugs, of course, is the risk associated with sticking a needle into the vitreous cavity. (PRP, in contrast, is destructive but non-invasive.) The primary concerns relating to the delivery include traumatic injury to the lens, endophthalmitis and retinal detachment or injury. However, post-injection complications have been infrequent in the treatment of wet AMD; even in the clinical trials, the rate of endophthalmitis and retinal detachment were miniscule (<0.1 percent).7

Currently, Genentech is exploring the possibility of conducting a multicenter clinical trial using Lucentis to treat NVG. Given the early data that has already appeared in the literature, such a trial seems like a worthwhile endeavor.

Reducing Scar Tissue?

The potential for using anti-VEGF drugs in glaucoma may extend to using them as adjunctive treatments for glaucoma surgical procedures. Exuberant formation of scar tissue leads to failure of trabeculectomy surgery and glaucoma drainage device implants; proliferating fibroblasts may block the egress of fluid into the formed bleb, leading to elevation of pressure. The use of mictomycin-C and 5-fluorouracil have led to a dramatic improvement in trabeculectomy success rates, but have also caused thinner blebs that are more likely to leak and become infected. At the same time, the use of antifibrotic agents in glaucoma drainage device surgery has not traditionally been associated with increased success.

It's clear that there is a need for novel agents in glaucoma surgery that can decrease fibroblast proliferation while not leading to extreme thinning of conjunctival tissue, and it now appears that anti-VEGF compounds may serve this purpose.6 (Another study supporting this conclusion was described in a report titled "The Effect of Avastin on Conjunctival Fibroblasts," presented by Joel Schuman's group at the March 2007 meeting of the American Glaucoma Society.) However, instead of applying the compound on the surface at the time of surgery—which would have a very short-term effect—we're injecting it into the vitreous where the vitreous acts as its own slow-release depot.8

We are each currently taking part in separate studies using Lucentis as a means to decrease scar tissue formation after glaucoma surgery. Dr. Lin's study involves using Lucentis in connection with Ahmed valve implantation; Dr. Kahook is exploring the use of intravitreal Lucentis in conjunction with MMC at the time of trabeculectomy. Both studies are in their early stages with data expected in the late summer or early fall of 2008.

What's Next?

Given the benefits of these anti-VEGF compounds, there may be other glaucoma-related applications for them as well. At least two centers have reported on the use of Avastin at the time of bleb needling procedures with promising results.5,9 Use of these agents with newer techniques such as Ex-PRESS device implantation, as well as with more established techniques such as cycloablation, is also under investigation.

Clearly, although we are still only in the initial stages of exploration, anti-VEGF agents hold real promise; they may very well turn out to be another important weapon in our glaucoma armamentarium. That's something we can all be happy about.

Dr. Kahook is assistant professor of ophthalmology and director of clinical research at the

1. Kahook MY, Schuman JS, Noecker RJ. Intravitreal bevacizumab in a patient with neovascular glaucoma. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2006;37:2:144-6.

2. Davidorf FH, Mouser JG, Derick RJ. Rapid improvement of rubeosis iridis from a single bevacizumab (Avastin) injection. Retina. 2006;26:3:354-6.

3. Silva Paula J, Jorge R, Alves Costa R, et al. Short-term results of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) on anterior segment neovascularization in neovascular glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:4:556-7.

4. Chalam KV,

5. Kahook MY, Schuman JS, Noecker RJ. Needle bleb revision of encapsulated filtering bleb with bevacizumab. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2006;37:2:

148-50.

6. Guerriero E, Yu JY, Kahook MY, SundarRaj N, Schuman JS, and Noecker RJ. Morphologic Evaluation Of Bevacizumab (Avastin) Treated Corneal Stromal Fibroblasts. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006 47: E-Abstract 1642.

7. Kourlas H, Abrams P. Ranibizumab for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A review. Clin Ther. 2007;29:9:1850-61.

8. Kahook MY, Olson JL. Treating Neovascular Glaucoma With Intravitreal Bevacizumab. Techniques in Ophthalmology 2007;5:4:150-153, 2007

9. Kapetansky FM,