Even some of the most successful cataract surgeons admit to an occasional posterior capsule rupture, a rare complication that can send even the most routine surgery on a tense and perilous 15-to-30-minute rescue mission. Experts in this article share insights about the best approaches. Find out the best ways to assess risk, respond confidently, complete surgery successfully and decide when to refer patients for retina follow-up.

Assessing Risk Factors

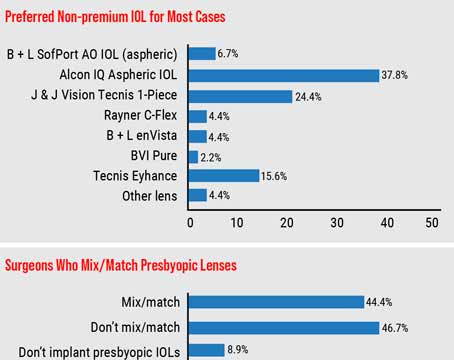

|

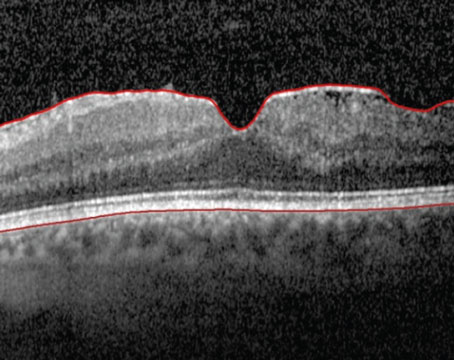

Surgeons say the first step to preparing for a posterior capsule rupture is understanding how one of these events can develop. Douglas K. Grayson, MD, of Omni Eye Services, which has multiple offices in the New Jersey-New York City area, points to causes and risk factors that range from the well-known to the less obvious. Like other surgeons, he cites two of the most common: posterior polar cataracts and dense lenses.

“It could also be a surgeon’s technical error,” he notes. “In addition, you could encounter a cataract that’s adherent to the posterior capsule, preventing you from removing it without causing a tear in an area of weakness in the posterior capsule.”

A posterior chamber rupture can also take you by surprise when you’re operating on a patient who has been treated for retinal disease, he points out. “What’s not realized is that when retinal patients receive Avastin, Lucentis, Eylea and steroid injections, retinal specialists can sometimes nick the posterior capsule,” he observes. “That will cause a small, focal weakening of the posterior capsule, which won’t be manifest until you go in with a phaco probe under infusion. You can’t even see that developing and, as a result, you’ll have a higher rate of posterior lens dislocation.”

|

Small pupil size, poor dilation, a history of preoperative trauma and poor patient cooperation can also increase risks, according to R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, Louisiana, and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Louisiana State University and Tulane Schools of Medicine in New Orleans. “If a patient is moving around, even with anesthesia, that alone may be the reason for the tear,” he says. “I also pay attention to significant increases in posterior vitreous pressure. You want to work on a nice, soft eye, but it can suddenly have an increase in pressure that can bulge the posterior capsule and vitreous forward.”

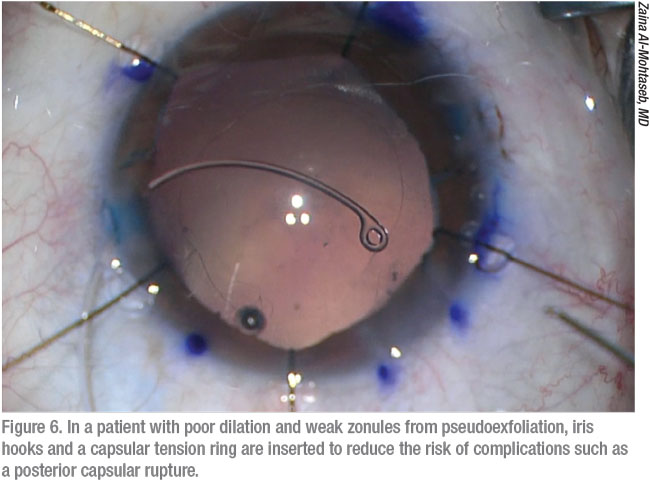

Zaina Al-Mohtaseb, MD, associate professor and associate residency program director at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, always has a higher level of concern with patients who have undergone prior retina surgery or have diseases such as pseudoexfoliation. “All cataract surgeons will have complications, and I have definitely had posterior capsule ruptures,” she says. “But I firmly believe that you should be prepared for possible complications and have everything you need, even though you won’t have to use those instruments most of the time. This is especially important when operating on patients at risk for complications such as a posterior capsule rupture and anterior vitrectomy.

Zonulopathy can also be associated with a history of trauma or mature cataract, adds Bryan S. Lee, MD, JD, in private practice at Altos Eye Physicians in Los Altos, California, and an adjunct clinical assistant professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University. “I do quite a few patients who are post-vitrectomy and those patients are more prone to have zonulopathy,” says Dr. Lee. “Sometimes, I know in advance that a patient is at higher risk of capsular break and that’s kind of easier to deal with. Even though I’m obviously trying to do everything I can to avoid a vitrectomy, if I need to do one because of a really bad cataract, I think, ‘Well, okay, I kind of knew this might happen.’ I can talk about it preop with the patient and be able to schedule accordingly, blocking off additional time in the operating room and letting the OR staff know that this could be a complicated case.”

In general, however, surgeons point out that risks factors for a ruptured posterior capsule are often not apparent. You need to be prepared for known and unknown co-morbidities that increase the risk of capsular rupture, zonular loss and unplanned vitrectomy, which can occur during any cataract procedure.

After Sudden Ruptures

|

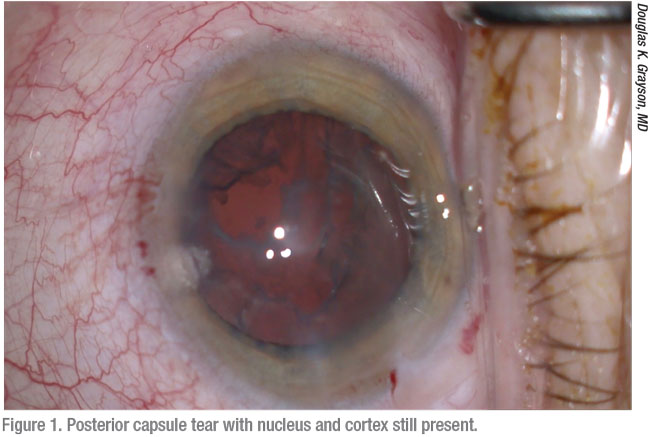

One common concern surgeons share is that they won’t respond properly if a posterior capsule ruptures during a case that’s expected to be straightforward. Dr. Al-Mohtaseb, who supervises residents at Houston’s Ben Taub Hospital, says she’s seen residents fail to even notice a posterior capsule rupture. “This can lead to much worse complications,” she says. “For example, if a surgeon doesn’t see vitreous and continues to phaco, that can result in retinal tears and detachments from traction on the vitreous.”

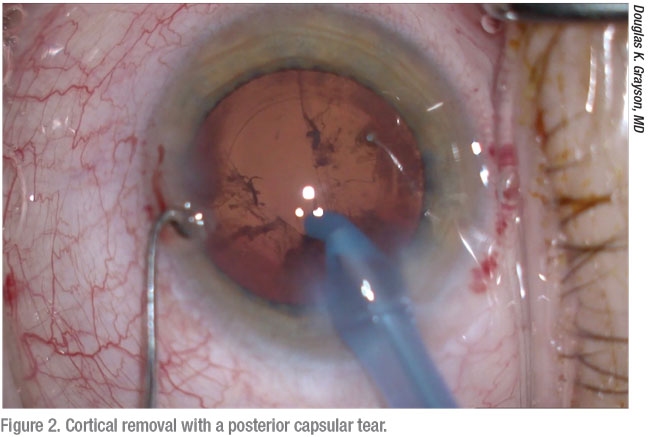

The second-worst response, she adds, is to become so stressed that you panic and suddenly remove all of your instruments from the eye. “Doing this flattens the chamber and causes more complications,” she points out. “Your best response is to remain calm and put OVD in the eye before removing the phaco probe. Then take a moment to set up the correct instrumentation for vitrectomy and use Triesence or Kenalog (triamcinolone, Bristol-Myers Squibb) to stain the vitreous. These cases can still go well. Your goal should be to try to avoid another surgery by not losing the lens or lens fragments posteriorly or by putting traction on the vitreous.”

In such cases, Dr. Lee agrees that panic can easily emerge as your archenemy. “Of course, arresting panic is easier said than done,” he admits, describing a sudden stream of worries that can flood his mind and disrupt a calm and measured response. “You start thinking about a lot of things at once: ‘I’m going to have to discuss this with the patient. Am I going to be able to put a lens in this patient? I want to do the right thing but I may have to change plans in the middle of the procedure. This is going to throw off my schedule. We’re going to fall behind.’ You have to block out all these self-defeating thoughts, deal with the situation, and make the best decisions you can under the circumstances to achieve the best result you can for your patient.”

Dr. Lee emphasizes that you shouldn’t stop irrigation and pull the phaco tip out of the eye right away. “If you do this, of course, the vitreous prolapses forward and possibly out through the incision,” he notes. “Traditionally and classically, dispersive viscoelastic is best to use in this situation, but the reality is that you have to use whatever is open. Your priority is to stabilize the eye and regroup.

“You have to pause and get members of the OR staff ready to help you,” he continues. “Tell them what equipment you need for dealing with the complication. Usually, I’ll administer a sub-Tenon’s block to make the patient more comfortable. You’re going to be manipulating the sclera and the case is going to take longer. At that point, your main goal is to try—if you can—to keep fragments from falling back through the posterior capsule rupture.”

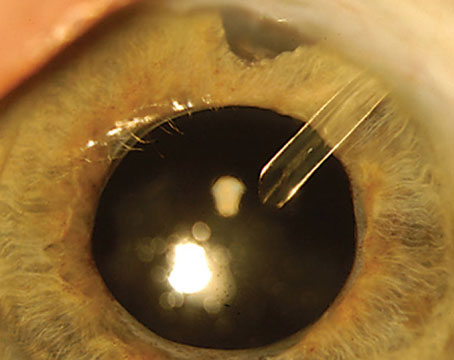

Effective Vitrectomy

In these cases Dr. Al-Mohtaseb recommends performing an anterior vitrectomy by going through pars plana (posteriorly) instead of through a corneal wound (anteriorly). “This way, you pull back vitreous and avoid traction,” she says. “I use Kenalog to not only highlight the vitreous but to provide an anti-inflammatory effect. I also use Miochol-E (acetylcholine chloride intraocular solution) at the end of the procedure to make sure the pupil is round. Then I suture the wound.”

|

Dr. Lee does a vitrectomy with a split infusion. “I make a sclerotomy to do my vitrectomy,” he adds. “Some surgeons aren’t comfortable making a sclerotomy and prefer to go through the limbus. Anatomically, the use of a sclerotomy offers the benefit of being more posterior, so that you’re more likely to keep the vitreous back. If you’re not comfortable making a sclerotomy, you can still do a good cleanup through the limbus. However, you definitely have to split the infusion and the vitrector. It’s important to know your machine and it’s settings.”

Dr. Lee starts his vitrectomy in the ICA (irrigate, cut, aspirate) mode, using a high cut rate that exceeds 2,000 cuts per second. At the end of the case, like others, he almost always use acetylcholine to constrict the pupil and to help maintain eye pressure. “I’m also checking for residual vitreous,” he adds.

|

Dr. Grayson does a vitrectomy through a sideport paracentesis. “All the machines currently have 25-ga. high-speed cutters,” he notes. “I create a paracentesis for infusion and put the cutter through the other side. Then I just clean up the vitreous in the anterior chamber and clean up the anterior vitreous in back of the posterior capsule. I don’t think anterior segment surgeons should start doing posterior stabs and going after nuclear pieces that have been dislocated into the posterior vitreous. If a nuclear fragment does go into the posterior segment, the best thing for us to do is to continue cleaning up the anterior vitreous and then determine whether you can put in some kind of a lens.”

Besides vitrectomy—and adding miotics—Dr. Wallace recommends that you consider doing a peripheral iridectomy. “This can pull the iris material away from the angle, avoiding a potential blockage that could develop with all of the activity present in that area,” he says.

Completing Surgery

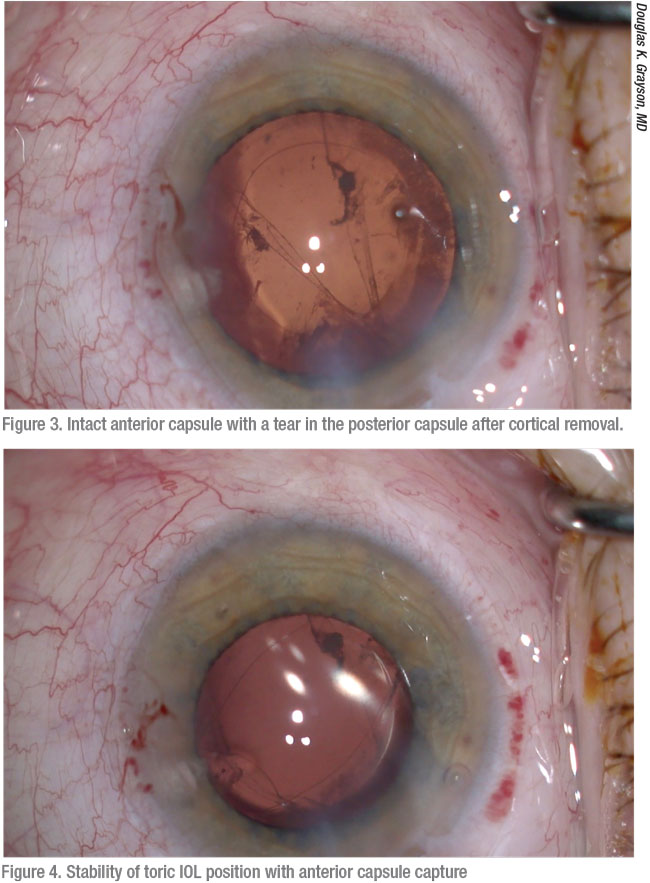

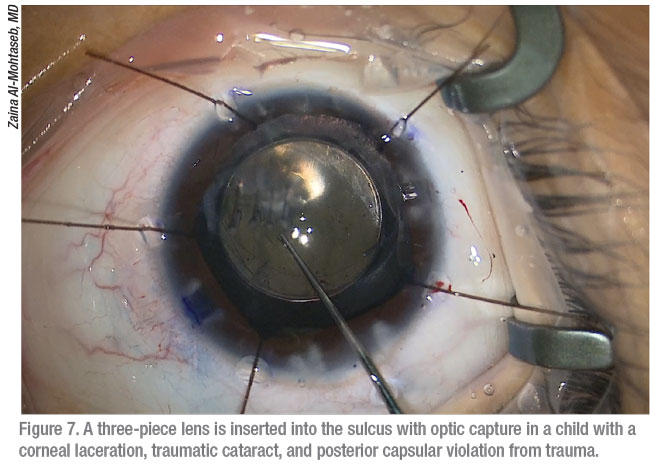

When completing cataract surgery after stabilizing the eye, Dr. Al-Mohtaseb says she rarely puts a one-piece lens in the bag, unless it’s a very small circular rupture. “I recommend implanting a three-piece lens in the sulcus, relying on optic capture,” she says.

|

Like Dr. Al-Mohtaseb, most surgeons seek alternatives to a single-piece IOL for these patients. “You occasionally will see a case in which surgeons will place a single-piece acrylic IOL in the bag, such as when they’re able to turn the tear in the posterior capsule into a posterior capsulorhexis,” says Dr. Lee. “But I would just go to a three-piece IOL.”

After a posterior capsule rupture, Dr. Lee explains that IOL stability can still be achieved even when the optic and haptics need to go into the sulcus, despite the misgivings of some surgeons. “If you can’t capture the optic, you can stabilize it by suturing the haptics to the iris,” says Dr. Lee. “But to be honest, it can be kind of hard to do that in this type of situation, when you have an unplanned vitrectomy. So it’s fine to put the lens in the sulcus and finish up the case. You can go back later to deal with the lens or suture it to the iris for more support—saving that part for another day, basically.”

Dr. Lee cautions inexperienced surgeons to not place a three-piece intraocular lens for the first time in a complicated cataract case. “It’s best not to try to learn how to do this implantation under these conditions,” he says. In his surgery center, however, where all of the surgeons are experienced, a three-piece is used as the default monofocal. “I’m very comfortable using a three-piece monofocal in all circumstances,” he notes.

Multifocal Uncertainty

After a posterior chamber rupture, Dr. Grayson says you may need to change plans if you were about to implant a multifocal IOL.

“Optimally, any IOL placed in the sulcus should have an anterior capsule capture for stability,” he says. “It’s advisable to use three-piece IOLs in the sulcus.” He notes that the only available three-piece multifocal IOLs you can use in the sulcus are Alcon’s Restor 3.0 IOL and Johnson & Johnson Vision’s Tecnis ZMAOO three-piece +4.0.

|

If the anterior capsule is not present enough for some degree of IOL capture, however, Dr. Grayson says the use of a multifocal may not be advisable at all. “That’s because a sulcus-placed IOL may move slightly,” he says. “This isn’t usually an issue for a monofocal IOL, but it may impact the optics of a multifocal. That changes your surgical planning for patients receiving multifocal IOLs, especially if your patient is scheduled to receive PanOptix or TECNIS Symfony IOLs.”

Even when implanting monofocal IOLs, of course, IOL power adjustments may be needed, Grayson continues.

“If it’s a pure sulcus placement, you should go half a power down on the IOL,” says Dr. Grayson. “But if you’re doing an IOL capture, I’d say you need to only decrease the power about a quarter of a diopter. You could potentially use the same lens. It’s important to make a compensation with the A-Constant as well.”

Taking a different approach, Dr. Lee says if you’re able to place the haptics in the sulcus and capture the optic, you should be able to keep the lens very stable and eliminate the need to change the IOL power. “If you’re not able to capture the optic of the IOL and need to place the optic in the sulcus, then of course you have to make IOL power adjustments,” he says.

When Dr. Al-Mohtaseb achieves an optic capture, she also doesn’t feel a need to adjust her IOL calculation. In the absence of an optic capture, she tries to avoid placement of the IOL in the sulcus, given the risk of the lens rubbing on iris, especially in myopic eyes. “In kids, I’d consider a posterior capsulorhexis, given the risk of posterior capsular opacification formation,” she adds.

Prolonged Cases

Dr. Grayson, like Dr. Lee, doesn’t think implantation of an IOL after a posterior chamber rupture is essential. “I’m thinking of an example of a long case involving a very hard cataract, after you’ve done a vitrectomy,” he says, “if you don’t get the lens in a good position, especially when you’re trying to place a sulcus lens with optic capture, or if you’re using an anterior chamber lens, you need to consider leaving the patient aphasic and coming back later. I’ve been in situations in which these patients start to move all over the place, and you start losing control. It’s totally acceptable to leave the patient aphakic, put a suture in the wound and come back another day to put in a secondary lens, especially if that patient is coming back for a secondary procedure to remove a retained lens fragment with a retinal specialist. You can just leave it and do it at the same time as the retina procedure. Another option would then be for the retina specialist to place a lens either in the sulcus or with posterior suture fixation, perhaps using the Yamane technique.”

After prolonged surgery associated with a posterior chamber rupture, Dr. Grayson advises you to wait until the patient’s cornea has calmed down before operating on the eye again. “You could have a few visits before you’re ready to go,” he says. “You just need to tell the patient, ‘We can fix it but we have to let the eye heal to get the best possible outcome.’ You don’t want to stuff a lens into an inflamed eye. Make sure the eye has healed and there’s no cystoid macular edema. You can easily wait two months before putting in a sulcus lens.”

Retinal Referral

“If you have any concern for retinal pathology or if you see any lenticular material in the vitreous, I’d recommend sending your patient to a retinal specialist,” says Dr. Al-Mohtaseb. “Some surgeons even consider sending all patients with posterior chamber ruptures for an exam by a retina specialist.”

Dr. Wallace agrees. “Of course, if there’s any question about nuclear material in the posterior segment, you should send patients to a vitreoretinal surgeon,” he says. “Referral to a retinal specialist is a good idea after any of these cases. The specialist can provide a second opinion and determine if any second surgery needs to be done. And the sooner you make that referral, the better. The longer you wait, the higher risk your patient has of developing posterior segment problems such as cystoid macular edema.”

Dr. Lee, who also often refers patients for retinal follow-up, takes a different approach than some of his colleagues. He says he finds that retinal specialists prefer that he put an IOL in when the posterior capsule ruptures. “I always try to have an IOL in the eye at the end of the case,” he says. “The only exception is if I have an IOL that dislocated posteriorly; then I certainly want to leave the patient aphakic. But that’s rare situation. Referring a patient to a retinal specialist in the presence of a retained nucleus can be critical because of the risk of a retinal detachment and the probability of needing a full vitrectomy.”

In terms of retained cortical material that’s not as dense and likely to dissolve upon observation, you can observe those patients closely, as long as you have a good view on a dilated exam, he adds. “But if you have any doubts, if you’re not sure how dense the material is back there, you’re always better off referring the patient and at least having the retinal specialist weigh in and decide whether or not it can be observed.”

Dr. Lee cautions against taking risks as a result of a noble, but misguided, attempt to spare your patient a follow-up procedure after a ruptured capsule. “If you see material falling back into the eye, it’s tempting to want to go back and get it,” he notes. “But you can get into trouble by trying to do more than your training and equipment allow you to do. Once nuclear material gets fairly posterior, you’re better off letting it go. Clean up the best you can anteriorly, put in a lens and leave the rest for the retinal surgeon.”

“There’s no downside to referring to a retinal specialist,” adds Dr. Grayson. “Sometimes, you will think none of the nuclear fragments went into the posterior chamber, but the specialist will find a fragment down in the vitreous.”

Quality Improvement

After a posterior chamber rupture, you may find it only natural to reflect and strive for improvement based on lessons learned. In an ideal world, Dr. Lee notes, you would record every posterior chamber rupture or other complication of cataract surgery on video. “You could review it, see what happened and try to figure out various things you might have done differently to get a better outcome,” he says. “Because of that, I try to tape all of my high-risk cases. That’s the ideal. But even if you don’t have the complication on tape, it’s important for your own development as a surgeon to think back later in the day, after you have finished surgery and everything is calmed down. Try to figure out what happened and what lessons you can learn.”

Dr. Lee says he’s learned something every time he’s “broken a bag.” He points out that surgeons are perfectionists. “We expect everyone to experience a great outcome,” he says. “It’s really hard on us when that doesn’t happen. At the same time, you have to accept the disappointment and try to turn it into something positive, which is what you learn from the experience. You become a better surgeon after every case.” REVIEW

Drs. Grayson and Wallace have no financial interest in the products discussed. Dr. Al-Mohtaseb has consulted for Alcon. Dr. Lee has consulted for J&J Surgical Vision and Alcon.