Here, three experts in the field discuss the current developments in this area, and offer their thoughts about what may lie ahead.

Avastin vs. Lucentis

The difference in price between Avastin and Lucentis has been a pivotal factor in the popularity of Avastin, but differences in effectiveness and safety are still being debated. “Both Avastin and Lucentis are potent, highly effective molecules—at least for wet macular degeneration—and they’ve been shown to produce similar visual outcomes,” says K. Bailey Freund, MD, a retina specialist who practices at Vitreous-Retina-Macula Consultants of New York and is a clinical professor of ophthalmology at the New York University School of Medicine. “A number of studies have compared the drugs head-to-head. It appears that Lucentis does a little bit better job of getting the macula dry and keeping it that way. In the CATT study, for example, more eyes had fluid with Avastin than with Lucentis, and patients who were treated only when they had fluid required fewer injections with Lucentis than Avastin.”

Dr. Freund notes that the differences between Avastin and Lucentis are more obvious when addressing conditions other than macular degeneration. “In wet macular degeneration there’s not a whole lot of VEGF being expressed that needs to be inhibited,” he points out. “In contrast, in acute central retinal vein occlusion there are extremely high levels of VEGF expression, so we tend to see more of the differences between the drugs when treating this condition. That’s also true in some patients with diabetic retinopathy. In my experience, the commercial drugs work better than Avastin in these situations, so I prefer to use them.”

Peter K. Kaiser, MD, the Chaney Family Endowed Chair in Ophthalmology Research at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine, and professor of ophthalmology at the Cole Eye Institute, agrees that vein occlusions may call for a different approach. “Macular degeneration is not really a VEGF-driven problem, whereas retinal vein occlusion and diabetic macular edema are,” he says. “Because of that, clinically we are seeing a bigger difference in efficacy between drugs, although we don’t have a comparison study yet to demonstrate that one drug is superior to the others. We will have results from a study comparing Lucentis, Avastin and Eylea for treating diabetic macular edema later this year. But for CRVO, we currently have no guidance until the SCORE 2 study is finished.

“I think with all of these diseases, many of us start with Avastin and only switch to a different drug when the patient doesn’t do as well as we expect. There’s really no reason to start with the more expensive drug.”

Dr. Freund notes that the obvious issues with Avastin are potential concerns of safety; in particular, the issue of compounding pharmacies. “In rare situations the drug has become contaminated, and in other countries such as China there have been issues with counterfeit Avastin being compounded,” he says. “But beyond those kinds of concerns, the CATT trial did show that there was a small, statistically significant difference between Avastin and Lucentis in terms of systemic safety, although it wasn’t one particular systemic adverse effect; it was distributed over many things. The difference was in favor of Lucentis, but it was a small difference, and many people have discounted it because it didn’t make a whole lot of sense. The systemic safety problems weren’t necessarily linked to the mechanism of action of the drug. Also, the other studies didn’t find that difference.”

Dr. Kaiser feels the evidence of safety differences doesn’t warrant a change in protocol. “From a standpoint of safety—outside of the compounding issue, which is still a big concern—there’s no compelling evidence that Avastin has any additional safety issues,” he says. “For most of us, that gives us the green light to use Avastin more frequently. Certainly many practices have turned to using Avastin first in all patients. They only switch the patient to another drug if Avastin fails to produce the desired result.”

“Overall, the Avastin vs. Lucentis debate has become a hotly contested area,” adds Dr. Freund. “Some people firmly believe that Avastin is as good as the other options in every way, at least for treating macular degeneration, while others point out the somewhat small but potentially real differences.”

A Third Option

With the Food and Drug Administration approval of Eylea in November 2011, surgeons had two approved anti-VEGF drugs to choose from, in addition to the off-label use of Avastin. This further enlivened the debate regarding which—if any—is superior.

Dr. Kaiser notes that the VIEW study in macular degeneration found Eylea to be similar in efficacy to Lucentis, while requiring fewer injections. “In this study, patients were able to go longer between treatments with Eylea than Lucentis,” he says. “Whether that difference remains in clinical practice remains to be seen. We are finding that many of our patients who fail to respond to Avastin or Lucentis do better when we switch them to Eylea, and several case series have found the same thing. So in my practice, I often start patients with Avastin. If they don’t respond to Avastin, I switch them to Eylea because of the longer duration, similar efficacy and lower cost compared to Lucentis. The exception would be diabetic macular edema, for which Eylea is not approved. In that situation I’ll switch to Lucentis if Avastin fails.”

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

“Eylea is very effective,” agrees Dr. Freund. “Our group and others have shown that some patients do seem to respond somewhat better anatomically—in particular, those who have proven resistant to the alternatives. Switching them may allow for less-frequent dosing. It’s labeled for eight-week dosing after the first three monthly treatments, which is quite different from the Lucentis label.”

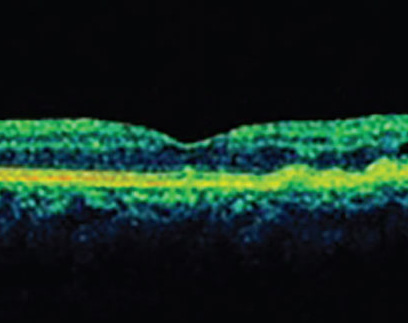

David M. Brown, MD, FACS, who practices at Retina Consultants of Houston and runs the Greater Houston Retina Research Center, has written extensively about the use of the different anti-VEGF options in macular degeneration, diabetes and retinal vein occlusion, and their comparative efficacy. “In terms of durability—getting the retina dry and keeping it that way longer—I think Lucentis and Eylea are definitely better for treating diabetic macular edema, and I think those drugs are better for at least half of all macular degeneration patients. If you look at the data from the CATT trial, monthly Avastin dried out about 30 percent of patients, while monthly Lucentis dried out about 50 percent. In Regeneron’s VIEW 1 and VIEW 2 trials, Lucentis dried out about 50 percent of eyes, similar to the CATT results, and Eylea dried out about 70 percent. That suggests that you’ll get more effective drying with Eylea than with Lucentis or Avastin.

“I believe that most people who have worked with all of these drugs extensively know that Avastin is less potent than the others,” he adds. “Even in the CATT trial, Avastin didn’t win in any category. Usually if you have drugs that really are equal, one drug will win in one category and the other will win in another category. Avastin didn’t win in any category. People keep saying that Lucentis and Avastin are equal, but if it’s my eye or my dad’s eye that’s in trouble, I’m using Lucentis or Eylea if I have a choice. However, as I said earlier, if you succeed in drying the retina out, it doesn’t matter which drug you used. So, I think it’s very reasonable to start with the cheaper drug.

“The biggest thing happening with Eylea is that they have a pending investigational new drug approval for diabetes,” he adds. “That could really change diabetes management, depending on the outcome of the direct head-to-head comparison of Lucentis, Avastin and Eylea for diabetes that’s in progress right now. The data should be out in January. My guess is that Eylea will turn out to be more durable, but we won’t know until we see the data. If it shows that Avastin is absolutely equal in every way, then I think every insurer will say you need to use Avastin, and that’s fine. If it shows that Eylea or Lucentis (or both) are superior, then we’ll be in the same situation we are with macular degeneration.”

Dr. Freund points out that Eylea was tested in two strengths: 0.5 mg and 2 mg. “It’s the 2-mg formulation that was approved, so we’re giving a fairly large dose of drug,” he notes. “Whether the drug itself is truly more potent than the others or we’re just giving more of an equally potent drug is still debated. But I think most retinal specialists have the impression that Eylea is somewhat more potent.

“Increased potency sounds really good,” he continues, “but there’s a concern that comes from the CATT and IVAN studies, the latter being the U.K. head-to-head comparison of Lucentis and Avastin. In both studies it was seen that patients who got more injections developed more geographic atrophy. That’s a big problem, because that’s often how patients end up losing vision over the long term; retinal cells die. So, a drug that’s more potent might reduce the number of injections needed but cause more geographic atrophy. It’s a theoretical concern at this point, but some people like myself are watching this very carefully. In our zeal to get maculas completely dry we could potentially be accelerating the dry aspect of the disease.

“If this is true,” he adds, “it will be hard to prove. It’s possible that if we analyze some of the data from recent trials we may be able to tell whether higher doses cause more geographic atrophy. But geographic atrophy is part of the natural course of the disease, so it will be hard to tease apart what the drug might be doing vs. the disease itself.”

Dr. Brown says he uses whichever drug keeps the retina dry. “If Avastin keeps the retina dry, whether it’s macular degeneration or retinal vein occlusion or diabetes, that’s fine,” he notes. “If however, you’re giving a patient a shot of Avastin every month and he still has persistent fluid, I think the patient would be better served by trying Lucentis or Eylea.”

The Insurance Factor

“The drug a surgeon uses depends in part on the insurers,” notes Dr. Brown. “More and more insurers are either doing a step edit, where they want you to use Avastin first, or they’re simply using a passive-aggressive strategy to avoid dealing with surgeons who use the expensive drugs. Medicare advantage plans are not supposed to restrict drugs any more than Medicare—they’re supposed to provide the same thing Medicare does. So they say you can use any drug you want, and then they drop providers who use the more expensive drugs. They say they’re making their provider pool smaller or consolidating, but if you look at the pool, the only people they keep on are doctors who never use Lucentis or Eylea. I’ve been kicked off of, or not selected for, most Medicare Advantage plans and HMOs in our market because I use Lucentis and Eylea in recalcitrant patients.

“Of course, this would never happen except in such an unusual situation,” he adds. “There’s no place else in medicine where you have a $50 drug competing with a $1,300 or $2,000 drug. And we’re in such a small field that they can kick us off their panels and it saves them money.”

Dr. Brown points out that many insurers won’t even allow a step edit. “I wish the insurance companies would allow that, even though the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has said that step edits aren’t appropriate,” he says. “As a result, in our practice we have to take the patient’s insurance into consideration. We know which insurers want us to use Avastin, even though they don’t say it. Patients with that insurance only get Avastin. With other patients we can do what we think is the best for the patient.”

Although Dr. Brown believes it’s reasonable to start a macular degeneration patient on Avastin, he notes that occasionally a patient won’t agree. “Patients,” he says, “sometimes make this argument: ‘I’ve got great insurance and I’ve been paying for it for a long time. Why are you making me start with a drug that’s not made to go into the eye and has a risk of endophthalmitis from a compounding pharmacy issue?’ In the final analysis, if a patient has good insurance, I start him on an approved drug—Lucentis or Eylea. If the patient is cash-pay or underinsured, I start him on Avastin. If that patient has lots of fluid, then I fight the insurance company to try to get one of the other drugs.

“Another option is to get the patient into one of the Access programs,” he notes. “The Access programs are pretty good at getting free drugs for patients who can’t afford them. These are charities originally developed by the pharmaceutical companies to provide access to chemotherapy for cancer. If you make less than $100,000, you can get free Lucentis or Eylea—but only if you don’t have insurance coverage. So the irony is that if you have a Medicare advantage plan that says ‘Yes, we cover Lucentis,’ you’re not eligible for the free drug. At the same time, you’re not really eligible for the insurance-covered drug, because your surgeon may be fired from the insurer’s panel if he uses it.”

Combination Treatments

For a number of reasons, one popular approach to trying to improve on the current drugs has been to look for new drugs and other procedures that might combine with the current drugs and produce even better outcomes. “Studies have looked at combining anti-VEGF drugs with photodynamic therapy, steroids and radiation,” notes Dr. Freund. “The problem is that these combinations sometimes reduce the number of injections needed, but none of the combination trials has yet matched the visual results achieved with anti-VEGF monotherapy.

“The exception may be combining anti-VEGF with another sophisticated pharmacological agent,” he continues. “There’s a drug called Fovista, currently undergoing a Phase III trial in combination with Lucentis; the combination is being evaluated in comparison with Lucentis monotherapy. Fovista targets platelet-derived growth factor, which is involved in the development of the pericytes that help in the maturation of neovascular vessels. In other words, Fovista inhibits the pericytes.”

Dr. Kaiser believes that in terms of combining drugs, using a PDGF inhibitor is at the top of the list. “Fovista is the first out of the gate,” he says. “The Phase II study showed very good results in comparison to anti-VEGF alone, resulting in a significant improvement in vision. If that’s replicated in Phase III, they’ll have a hit on their hands because we’ll have a treatment that actually improves vision over our current anti-VEGF therapies. Of course, this means patients would undergo two injections, but they won’t care as long as they’re getting better results. My patients would be willing to do three or more injections every month if it would improve their vision, especially since they would be done at the same visit.”

“Regeneron and Bayer have also announced that they’re working on an anti-PDGF agent,” Dr. Freund notes. “The potential benefit of their formulation is that it could be co-formulated with Eylea. In contrast, in the Fovista trial the patients have to get two injections back-to-back; you can’t mix the two drugs. So if the strategy of using Fovista in combination with one of the existing drugs gets FDA approval, it will have to be given the same way. That’s a drawback, so the trial will need to show a fairly substantial benefit over Lucentis alone to make it something that doctors and patients would want to do. But it’s certainly possible. Also, if you did this a number of times it might result in fewer injections being needed down the road, but we don’t know if that will be the case.”

Dr. Freund says another potential combination drug worth noting is squalamine lactate, a topical therapy. “That’s being used in combination with anti-VEGF in hopes of reducing the treatment burden,” he explains. “It’s currently in clinical trial. It’s felt to be a fairly potent antiangiogenic molecule that can reach therapeutic levels in the retina with topical dosing.”

Dr. Brown notes that there are some Phase I trials combining other antiangiogenic agents with an anti-VEGF drug. “One that’s combined with Lucentis is coming from Roche; another that combines with Eylea is from Regeneron,” he says. “It’s nearly impossible for anyone other than a big pharmaceutical company to conduct a trial like this, because only they can provide the anti-VEGF drug without having to buy it. In any case, these options are three to seven years away, assuming they pan out. In the near future, however, there is a proposed Phase III trial of an Alcon anti-VEGF drug that looks encouraging.”

Dr. Freund adds that the reason many of these are combination trials is that it would be unethical to do a trial of a drug vs. placebo. “This way the subjects in both groups get a proven therapy, and maybe the group getting the new drug won’t need as many injections,” he explains. “In the case of squalamine lactate, I also believe it would be a bit of a reach to think that any drug used topically as monotherapy could compete with a drug being injected intravitreally.”

Anti-VEGF and Radiation?

In terms of combining anti-VEGF with radiation, Dr. Freund says studies have not borne out the Neovista approach. “The Neovista approach involved doing a vitrectomy and inserting a probe into the eye,” he says. “Now there’s an office-based IRay radiation system that uses external beam radiation that’s in clinical trials. But I am skeptical that radiation is really going to be an effective treatment. It has a fairly narrow therapeutic window. If you give too much you’ll cause radiation retinopathy; if you give too little, it may not impact the disease you’re trying to treat.”

“Radiation in combination with anti-VEGF therapy is still being looked at,” notes Dr. Kaiser. “It’s gotten farther in Europe than in the United States. The INTREPID study for Oraya’s IRay system has shown a decrease in the number of injections, with similar visual results, when used in combination with anti-VEGF. It’s only approved in Europe, but we’re hoping for a Phase III study in the United States.”

Dr. Brown believes combining anti-VEGF drugs with radiation is unlikely to be widely adopted. “The data shows that doing this doesn’t produce improved visual acuity,” he points out. “I present at meetings every month and talk about anti-VEGF trials where patients gained two or three lines, so an alternative that doesn’t lead to improved vision, to me, is not viable.”

Staying Out of Trouble

These strategies can help prevent problems from arising:

• When treating diabetic macular edema, don’t wait to start the injections. “The data shows that if you wait a year, you never get the gains you would have gotten,” Dr. Brown points out. “No matter which drug you’re using, start injecting these patients sooner rather than later. Nobody holds off injecting patients with macular degeneration, because everybody knows that the eye will be far worse off in a couple of months if you don’t treat. With diabetes, it’s a lot easier to postpone starting while you’re managing other things such as blood pressure control and systemic concerns. But the longer you wait to start injections, the less chance you have of robust gains.”

• Be especially careful about managing your cash flow relating to Lucentis and Eylea. “More and more we’re seeing some secondary insurers dragging their feet about paying their portion of the coverage,” says Dr. Brown. “If you’re using anything other than Avastin and 10 percent of your secondaries are delaying payments for a while, stretching them out to 90 days or more, you might not notice it at first because some money is coming in. But the delay in reimbursement can add up and really hurt your practice. You need to figure out which insurers are delaying payments, and then either talk to those insurers or consider using mostly Avastin with patients who have that insurance.

“Sequestration has also made it harder to use Lucentis and Eylea by cutting the margin from 6 percent to 4 percent,” he adds. “That makes it even tougher to manage these drugs.”

• Pay attention to your compounding pharmacy. Dr. Freund notes that managing compounding pharmacy concerns is tough. “You attempt to evaluate your pharmacy as much as possible, but you can’t know for sure what procedures are being followed in actuality,” he says. “I’ve had the unfortunate experience that three of the compounding pharmacies I’ve used over the course of my career—all except the one I’m currently using—were shut down by the FDA because of serious concerns. Years ago I ordered some drug from the New England Compounding Pharmacy; that was the one that had the fungal contamination of steroids that killed patients with encephalitis. Franks Pharmacy, in Pensacola Fla., was shut down for fungal contamination of drugs. And the pharmacy that I was using up until recently failed to tell doctors that one of its batches had failed the sterility test, so they had their license suspended. Some of the best institutions in the country were using these pharmacies. While situations like this are rare, it’s a real concern.

|

“The compounding pharmacy laws are trying to create more oversight,” notes Dr. Brown. “That’s a great idea; we want to give safer Avastin to our patients. But the downside of the increased oversight is that some pharmacies are now requiring individual prescriptions. We can’t provide an individual prescription for every patient to get the drug; it would simply be too difficult. The FDA’s role is to protect the U.S. population, so it makes sense to have these new regulations. However, they may end up limiting the use of Avastin and increasing Lucentis and Eylea use—which the insurance companies won’t like.

“I do think surgeons should opt for the certified pharmacies,” he adds. “Hopefully, the practical concerns being raised by the new laws can be resolved. In any case, every practice should do a lot of due diligence, checking carefully to find out what the pharmacy you’re using is doing. Does it test the compounded drug for toxins? For bacterial contaminants? How many times has it had problems? If a pharmacy starts to require prescriptions we’ll switch to a different pharmacy, but we’ll do a lot of careful checking to make sure the drugs are safe.”

Dr. Kaiser agrees. “I think the key is to make sure that the pharmacy that you’re buying your Avastin from is certified,” he says. “Then, make sure you periodically double-check the pharmacy’s status. Finally, make sure your pharmacy checks the sterility of every batch. Pharmacies don’t necessarily do this, but they should.”

• Inspect the drug package when it arrives from the compounding pharmacy. “If the package looks like it went through a freeze-thaw cycle, send it back,” says Dr. Kaiser. “You wouldn’t want to use that batch. If it looks like the packaging is all wet, as if the ice melted, that’s a big tipoff.”

In the Pipeline

Naturally, more anti-VEGF drugs are on the horizon. “Another drug with potential is ALG-1001, an integrin antagonist from Allegro,” says Dr. Kaiser. “Integrin antagonists use a different approach to angiogenesis. ALG-1001 is interesting because not only does it seem to work as monotherapy, it also appears to work in combination with anti-VEGF. Right now the big question is, should the initial testing be done as combination therapy or monotherapy? It seems to work by itself and have a long-lasting effect, but it takes a little time to get going. Using it in combination with an anti-VEGF drug may be beneficial because you’ll get both the immediate wow factor and the long-lasting effect from the new drug.”

“Another anti-VEGF agent that’s gotten a lot of attention is Allergan’s drug, previously known as Darpin, now called Abicipar,” notes Dr. Freund. “They had some issues with inflammation, but they’re reformulating. That’s thought to potentially be a very potent anti-VEGF agent.”

New delivery methods are also promising, in particular because they may eliminate the need for repeat injections. “In wet macular degeneration, the next big thing may be sustained-release anti-VEGF treatment, allowing us to do one treatment that lasts a lot longer,” notes Dr. Kaiser. “One approach to this is gene therapy, which would cause anti-VEGF to be released indefinitely. Another approach is the Neurotech method, in which you surgically implant genetically altered RPE cells in a little cylinder. They release the anti-VEGF drug for as long as the implant is in the eye. The latter approach seems safer to me, since when the treatment is done you can remove the cylinder. You can’t turn off the gene therapy, which is a little concerning. Testing of the Neurotech system is just starting, though, so we probably won’t have it for a few years.”

One key factor in new drug development will be Lucentis and Avastin going off patent a few years from now. “In 2019 Lucentis and Avastin go off patent, so if you’re doing the numbers on whether to go through a drug-approval process you have to look forward,” says Dr. Brown. “It takes three to five years to go through that process, and you’re probably going to be competing with other cheaper agents at that point—biosimilar Lucentis and Avastin drugs.”

The other key factor is creating a drug that can produce better results than the current drugs, which is not an easy thing to do. “We all hope something will be the next big blockbuster, but it’s really hard to surpass the data from the previous trials,” Dr. Brown points out.

Taking Action

Dr. Freund notes that all of the current options are viable, so the main issue is getting treated in time. “Comprehensive ophthalmologists who aren’t treating with intravitreal injections should be aware that we now have some really good therapies and multiple choices,” he says. “The key thing is to identify these patients and get them to a physician who can treat them properly. As a retina specialist, there are pros and cons to each drug, but you can’t really go too far wrong with any of the three current drugs for treating macular degeneration. They all work well.” REVIEW

Dr. Freund is a consultant for Genentech, Bayer and Regeneron. Drs. Kaiser and Brown are consultants for all of the companies whose products are mentioned.

1. Papadoloulos N, Martin J, Ruan Q, et al. Binding and neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and related ligands by VEGF Trapm ranibizumab and bevacizumab. Angiogenesis 2012;15:2:171-85.

2. Vinores SA. Technology evaluation: Pegaptanib, Eyetech/Pfizer. Curr Opin Mol Ther 2003;5:6:673-79.

3. Freund KB, Mrejen S, Gallego-Pinazo R. An update on the pharmacotherapy of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2013;14:8:1017-28.