A Small Package

One of the chief benefits Ziemer (Port, Switzerland) touts about its new femtosecond laser is its relatively small size.

"It's small and mobile enough to be rolled up beside an excimer," says Anton Wirthlin, PhD, Ziemer's vice president of marketing. "And the surgeon uses the same bed and microscope as the excimer as he creates the flap. Like using a microkeratome before LASIK, you don't have to move the patient or relocate yourself. It weighs about 400 lbs., but comes on wheels, so it can be pushed and then locked in place." He says that this rolling around doesn't throw the laser out of calibration, and it can be rolled into a van and taken to a separate office without having to be recalibrated. Once it's plugged in at the new location, it goes through its own diagnostic routine, and Dr. Wirthlin says it would be ready to use in less than an hour. Size-wise, the DaVinci laser is around 3 feet long, 28 inches wide and 40 inches tall.

|

| The DaVinci's articulated arm can reach over to the patient on the excimer laser bed, avoiding the need to move the patient to make the flap. |

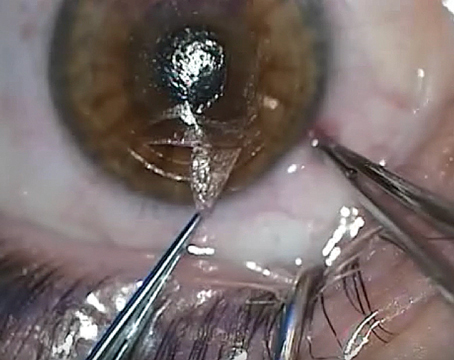

The surgeon is able to use the excimer laser's patient bed and microscope with the DaVinci because the new tool uses a laser handpiece connected to an articulated arm to deliver the energy to the eye. This arm can swing out to either side of the DaVinci's boxy body to where the patient is. The handpiece is another aspect of the device which the company compares to a microkeratome, in terms of usability.

"Since the handpiece is on the end of the articulated arm, this basically allows you to assemble the handpiece completely before you approach the patient to create the flap," explains Dr. Wirthlin. "The surgeon's assistant assembles the suction ring, sterile interface shield, suction tubing and some sterile handpiece covers ahead of time, so the workflow is similar to that involved with a microkeratome, which is assembled ahead of time and ready for use. The assistant swings the arm over to the doctor, who guides it over the patient's eye and monitors its positioning over the eye using the excimer's microscope. Once he has achieved good suction, which is controlled and confirmed by the machine, he can make the flap."

A Look Under the Hood

Ziemer says the DaVinci uses a new way to generate femtosecond laser pulses.

"The traditional way for a femtosecond laser to generate pulses is a dual-stage process," says Dr. Wirthlin. "In it, you have a source that generates the beam and determines pulse rate, then a second stage amplifies the beam to the energy level for what you need to do, which in this case is to cut tissue. Our laser is single-stage; the oscillator generates enough energy without the need for an amplification stage, and it operates in a range measured in megahertz. The higher the frequency, the shorter the pulse. The shorter the pulse, the more pure the tissue dissection is. At a lower pulse frequency, on the other hand, you get part dissection, part disruption and part evaporation."

Dr. Wirthlin says this short pulse means the DaVinci doesn't produce cavitation bubbles immediately after flap creation, which could take several minutes to clear before the surgeon can perform the excimer ablation. He says they also eliminate bubbles by focusing the beam from a point closer to the eye, usually a few millimeters rather than several centimeters, which can affect the way the energy is focused.

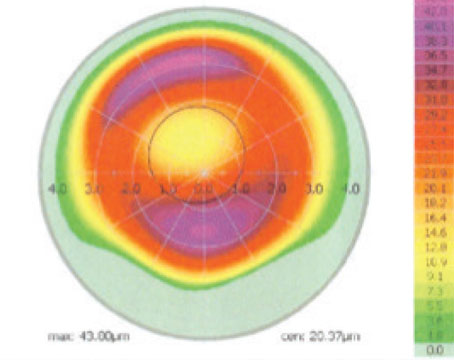

Since the DaVinci lays down spots that are about 2 µm in diameter, the company says the laser doesn't leave residual "tissue bridges" in its wake as it makes the flap. These bridges are actually tiny corners beside the spots that the laser didn't touch, and therefore aren't separated. They have to be forced apart after the laser cutting is done using a spatula, which can occasionally require a good deal of effort, according to some surgeons.

"In our case, we tightly overlap the spots, giving a continuously cut surface with no spaces in between and a flap that can be lifted easily with a spatula without much force," says Dr. Wirthlin. Though these observations were initially made with model eyes, Dr. Wirthlin says they have since been confirmed in live patients.

One issue often discussed in the LASIK flap-making debate is the time required to create a flap. Dr. Wirthlin thinks the DaVinci is competitive on this front.

"The actual flap cutting time is comparable to other systems," he says. "It's around 30 seconds, depending on the actual pattern that you're cutting and other factors." Dr. Wirthlin notes, however, that if one looks at the total procedure time, or the "on-eye" time, including setup and patient positioning, the DaVinci is quick. "The surgeon doesn't need to assemble anything on the eye of the patient; he uses the handpiece as he would a microkeratome," he says.

The DaVinci is available for sale now, but units won't be available for delivery until June. The cost is $429,000, and the disposables involved with the procedure cost about $100 per eye.