Providing optimal care to patients with primary open-angle glaucoma is a constant challenge in today's busy practices. According to the results of a survey of the membership of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, the average number of patients seen each week by the typical comprehensive ophthalmologist has increased from 115 to more than 160 per week during the past 5 to 10 years. At the same time, new knowledge gained from recent studies such as the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study and the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial have increased the recommendations for care that we provide to our patients.1,2

In a recently published study of patients with POAG in a managed-care setting, my coworkers and I assessed whether those patients were receiving a level of care consistent with the recommendations of the AAO's Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines.3,4 In contrast to our earlier studies of treatment data that were collected from a single area,5,6 we reviewed the care received by working-age enrollees of six commercial managed health-care plans located throughout the United States (one in the Northeast, three in the Midwest, one in the South, and one in the West) between 1997 and 1999. Mean patient age was 54.7 years.

In this study, we examined administrative data from the insurance plans, conducted a patient survey and reviewed eye-care records from the providers' offices. In addition, we assessed the care provided at initial exams and follow-up visits, control of intraocular pressure at follow-up visits, intervals between follow-up visits, intervals between visual field tests, and adjustments in therapy.

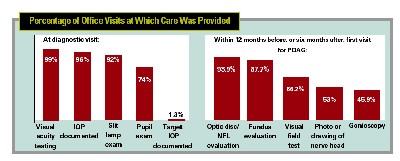

In general, we found that patients with POAG in our study often received care consistent with the AAO's guidelines. However, there were still a few notable opportunities for improving the care that we provide. For example, our study found that during the exam at which POAG was first diagnosed:

• 99 percent of patients received visual acuity testing;

• 96 percent had their IOP documented;

• 92 percent of the exam records we surveyed included the results of a slit lamp exam;

• 74 percent of patients received a pupil exam.

If we extended the time period to include the 12 months prior to the diagnosis date and the six months after the diagnosis date (a period of 18 months), we were able to discern documentation of the following at least once:

• 94 percent had some form of documentation of the nerve, even if it was only a record of the cup-to-disc ratio or a description such as "cupped" or "abnormal";

• 66.2 percent received a visual field test;

• 53 percent had documentation of the optic nerve via a drawing or photograph;

• 45.9 percent had gonioscopy.

Notably, at the initial visit for POAG, only 1.3 percent of the charts documented a target IOP.

Based on the results of our study, as well as data from other related studies, there are several steps any practice can take to help make the level of care more consistent with that recommended in the PPP.

• If you diagnose or suspect glaucoma, examine the optic nerve and document your assessment. We all know that examining the optic nerve is an essential part of caring for glaucoma and glaucoma suspect patients. In the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study, half of the cases of progression were determined by optic disc characteristics alone, without visual field loss. Yet our study found that examination of the optic nerve, and documentation of that exam, were far from consistent.

For example, if we look at the initial visit at which the diagnosis of glaucoma was made, plus the subsequent visit, less than three-quarters of the charts had an optic nerve head examination of any kind documented. (If we stretch that interval to one year before and six months after diagnosis, the number rises to about 94 percent.)

Also, studies of follow-up care that we've done in the last 10 years have found that about 80 percent of specialists document some form of optic nerve exam within the two years preceding or during the current exam. However, less than half of the charts in community-based practices indicated that an optic nerve exam had taken place during the same time interval.

• To document the nerve, take a photograph or create a drawing. We found that when an optic nerve exam is documented, methods and extent of documentation often do not include the use of drawings or photographs, as is recommended by the PPP. Determining whether progression has occurred without some detailed documentation of what the nerve looked like at previous exams is difficult, yet documentation is typically a simple c/d ratio without additional detail, or a general verbal description such as "cupped."

Overall, less than 30 percent of all optic nerve exams over the course of care included a photograph or drawing. (In specialists' offices about 35 percent of glaucoma patients have a photo taken each year.)

• Set a target IOP. As mentioned previously, our study found that only 1.3 percent of POAG patients had a target IOP set by the doctor at their diagnostic visit. This is problematic, because many of the recommendations for care (and the intervals between visits and diagnostic tests) in the PPP depend on whether the patient's IOP is above the target or not.

It's likely that the doctors did decide on a target IOP, but they didn't document it. Unfortunately, lack of documentation can lead to inconsistent care over time and across providers.

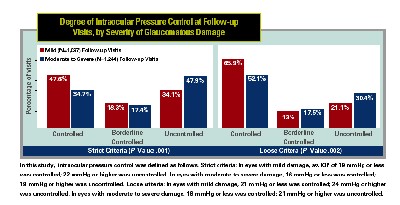

• Don't undertreat. POAG may be undertreated relative to the standards for IOP control established in recent clinical trials. In our study we examined this factor from two perspectives: using strict criteria for control, and using loose criteria.

Using strict criteria, patients with mild visual field damage had controlled IOP in both eyes at less than half of their follow-up visits. (Using looser criteria, the number rose to two-thirds.)

Patients with moderate to severe visual field damage had IOP under control in both eyes at only one-third of follow-up visits. (Using looser criteria, the number rose to slightly more than one-half.)

Mean IOP level was similar for patients with mild visual field damage (a mean of 20 ±4.7 mmHg in study patients) and those with moderate to severe visual field damage (19.6 ±5.7 mmHg).

• Watch intervals between exams and visual fields. In some respects, this factor was well-managed. Intervals between visits were shorter for patients with more severe damage, or worsening control of IOP, and patients with more severe damage had visual fields more frequently than patients with mild damage. However, for patients with moderate to severe damage, more than two-fifths of the intervals between visual fields were longer than 12 months, and nine percent of the intervals between visual fields were longer than two years.

Opportunities to Improve Care

Although our data suggest that our care of POAG patients does have room for improvement, our study comes with important caveats and limitations. Most importantly, the care provided to our patient sample (mostly Caucasian, employed and able to afford health insurance) may not be representative of care provided to patients in other managed-care groups, or nationally. However, the results of this study are consistent with our earlier studies in different populations.

As such, our data point towards areas in which we can update our care patterns and help bring the benefits of our new knowledge and therapies to all of our patients.

1. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, Parrish RK 2nd, Wilson MR, Gordon MO. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: A randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120:6:701-13; discussion 829-30.

2. Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Komaroff E; Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial Group. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: The early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:48-56.

3. Freemont AM, Lee PP, Mangione CM, Kapur K, Adams JL, Wickstrom SL, Escarce JJ. Patterns of care for open-angle glaucoma in managed care. Arch Ophthalmol 2003;121:777-783.

4. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Patterns: Primary Open-angle Glaucoma. San Francisco: AAO; 2003.

5. Albrecht KG, Lee PP. Conformance with preferred practice patterns in caring for patients with glaucoma. Ophthalmology 1994;101:10:1668-71.

6. Hertzog LH, Albrecht KG, LaBree L, Lee PP. Glaucoma care and conformance with preferred practice patterns. Examination of the private, community-based ophthalmologist. Ophthalmology 1996;103:7:1009-13.