Concerns over flap complications are enough to make some surgeons switch to other refractive procedures, or to never take up LASIK in the first place. Though complications with the flap and the interface are troublesome, you can manage them and give your patients a good result. In this article, I'll explain how I approach these problems in my practice.

Avoidance

Of course, the best way to manage complications is to never have them. You can come closer to this goal by taking certain steps.

First, dampen the surgical gauze around the patient's eye. This decreases the number of fibers that can break loose from the dressing and settle at the stromal interface.

There are two things I do a little differently to achieve good suction. After applying the microkeratome's suction ring, I put pressure on both sides of the ring to set it in place for about two or three seconds. This makes an indentation in the conjunctiva, helps achieve better suction and avoids the eye drifting under the microkeratome. I also use a pneumotonometer to ensure that the intraocular pressure is at least 80 mmHg prior to proceeding with the cut. Because I use the Hansatome, which makes a superiorly placed hinge, I slightly decenter the ring in that direction. Since the flap is not completely circular, this will ensure I've got ample stroma to ablate and won't hit the hinge with the laser.

|

| Figure 1. When faced with flap folds, ironing them with the Pineda Iron can sometimes smooth them out. |

Another tip with the Hansatome: Make sure the pole on which the keratome sits is tilted a little temporally. This allows the keratome to fit better, because, as you bring it in with your other hand to set it on the pole, it's never completely vertical. You'll find it fits in with less manipulation.

Also, using a large-diameter flap (around 9 mm or larger) allows me to better handle many of the complications listed here and minimize the chance they will occur. Since the edge of the flap is farther away from the visual axis, there's a reduced risk of visual distortion if sutures are needed. A large flap also gives me more time to intervene in cases of diffuse lamellar keratitis and epithelial ingrowth, which usually start at the periphery.

If Complications Occur

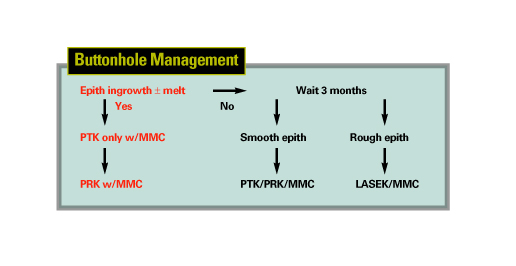

• Buttonholes. These can be near buttonholes or frank ones. A near buttonhole occurs when you have an island of Bowman's layer but without a breakthrough of the blade through the epithelium of the flap. In a frank buttonhole, the blade breaks the epithelium.

In both near and frank buttonholes, I'll almost always lay the flap back down to let it heal for about three months. If a patient has a near buttonhole in the periphery, however, I will consider treating him. If either a near or a frank buttonhole is in the center of the flap, however, I won't proceed with the case.

When I return to the eye three months afterward, I'll use either PRK with alcohol-assisted removal of the epithelium (if the surface is irregular) or phototherapeutic keratectomy epithelial removal (if the surface is smooth). In either case, I'll use 0.02% mitomycin-c applied for two minutes as an adjunct during the procedure to help avoid haze.

|

In both kinds of buttonholes, I avoid recutting the flap at all costs, since this can result in double flaps or create small, shriveled pieces of tissue that can be very difficult to deal with.

• Buttonholes with epithelial ingrowth. If a patient returns a few days later with cells growing through the buttonhole, I'll treat immediately.

Treatment consists of two stages: For stage one, I'll perform a PTK at a depth of about 50 µm. I'll then take the patient to the slit lamp to check and see if the epithelial ingrowth was obliterated. I'll use MMC during this PTK treatment, as well. If the ingrowth is gone, I'll perform the optical ablation, decreasing the target refraction by 20 percent.

If the ingrowth's still there, I'll perform another PTK, at a depth of

10 µm, and examine the eye again. I'll continue these small PTK treatments until no ingrowth remains, and I'll delay the refractive treatment until the refractive error can be determined.

• Partial flaps. If the microkeratome stops or is impeded before it reaches the projected hinge location, the eye can have an incomplete flap.

The best thing to do is stop and return about three months later; restarting the microkeratome risks an uneven bed and induced astigmatism. If the hinge is beyond the visual axis, you may be tempted to finish the flap with a blade. Resist this urge, since you can create an uneven bed or a buttonhole.

For the reoperation, I'd rather perform surface ablation than try to recut the flap, though the latter is possible. To get the best results if you choose to recut, enter the cornea deeper than before and in the periphery.

• Peripheral epithelial ingrowth. If the patient has cells coming in from the periphery of the cornea, I check to see how extensive the ingrowth is, assuming that it's probably more extensive than what I can see at the slit lamp. I follow the patient very closely with topography and refraction, looking for any signs of corneal melting. A melt would manifest itself as either flattening on topography or a hyperopic shift. Epithelial ingrowth that's connected to the flap edges is more worrisome than islands in the periphery, because the former has a source of cells that's feeding it, while the latter doesn't.

If the ingrowth is progressive, close to the visual axis or causes melting, I lift the flap and lay it on an instrument I designed but have no financial interest in, the Melki Flap Stabilizer (Rhein Medical, Tampa, Fla.). This is a small, ventilated, vacuum platform that connects to the microkeratome's vacuum console. The suction allows me to hold the reflected flap still, and gives me a backing to use for scraping it. I scrape both the stromal bed and the undersurface of the flap, taking care to scrape the whole surface, not just where cells are visible. I then replace the flap and apply a bandage contact lens.

If cells return, I place sutures at the edge of the flap for two weeks.

• Flap folds. I define these as either visually significant or insignificant.

If the patient suffers a decrease in acuity or a visual aberration from a fold, the sooner the flap is lifted, the better. In such a case, I lift the flap, place it on the stabilizer, then massage it with the Pineda Iron (ASICO, Westmont, Ill.) (See Figure 1.). The iron has a broad base that exerts even pressure on the folds. I replace the flap, iron it again, and place a bandage contact lens.

If folds persist, I perform a central epithelial alcohol debridement. I place a 5-mm well on the cornea and fill it with 20% alcohol for 30 seconds. I then use a flap lifter to mobilize the epithelium in a manner similar to LASEK. I then have two flaps: the epithelial one I just made and the original LASIK one below it. I move the former out of the way with the flap lifter and iron Bowman's layer. I put the epithelial flap back over it. This helps eliminate the epithelial hyperplasia in the crevices of the folds and lets me stretch the flap.

If the folds remain, I place seven or eight interrupted sutures radially around the flap, leaving them for two to three weeks. When I remove them, I prescribe steroids to avoid the possibility of DLK.

Though complications such as buttonholes and epithelial ingrowth can keep surgeons up at night, perhaps the strategies outlined here can let them rest a bit easier.

Dr. Melki is director of the Boston Eye Group and is an associate surgeon at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary at Harvard Medical School.