Workup, Diagnosis and Treatment

The differential diagnosis for insidious-onset vitritis in an elderly patient is broad and should include infectious and inflammatory etiologies as well as neoplastic conditions that may masquerade as vitritis. Infection, particularly in light of this patient’s relative immunocompromise secondary to chronic oral corticosteroid use and mycosis fungoides, should be excluded. Infectious etiologies to consider include bacterial or fungal endophthalmitis, HIV, tuberculosis, Lyme disease, toxoplasmosis, HZV/VZV, Bartonella and syphilis. Inflammatory conditions causing posterior or intermediate uveitis may present similarly, and include sarcoidosis and multiple sclerosis. Finally, neoplastic conditions such as vitreoretinal lymphoma should be considered, particularly in an older patient with prior oncologic history.

|

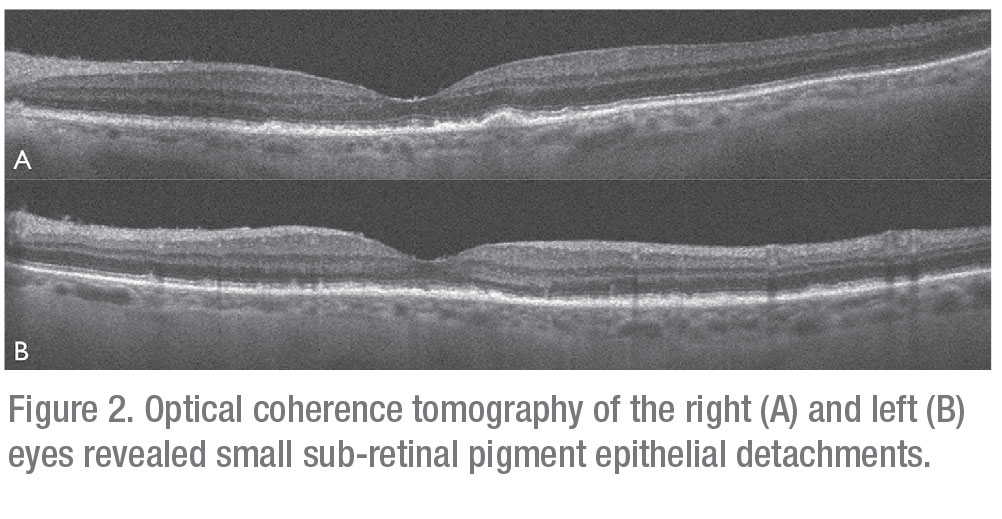

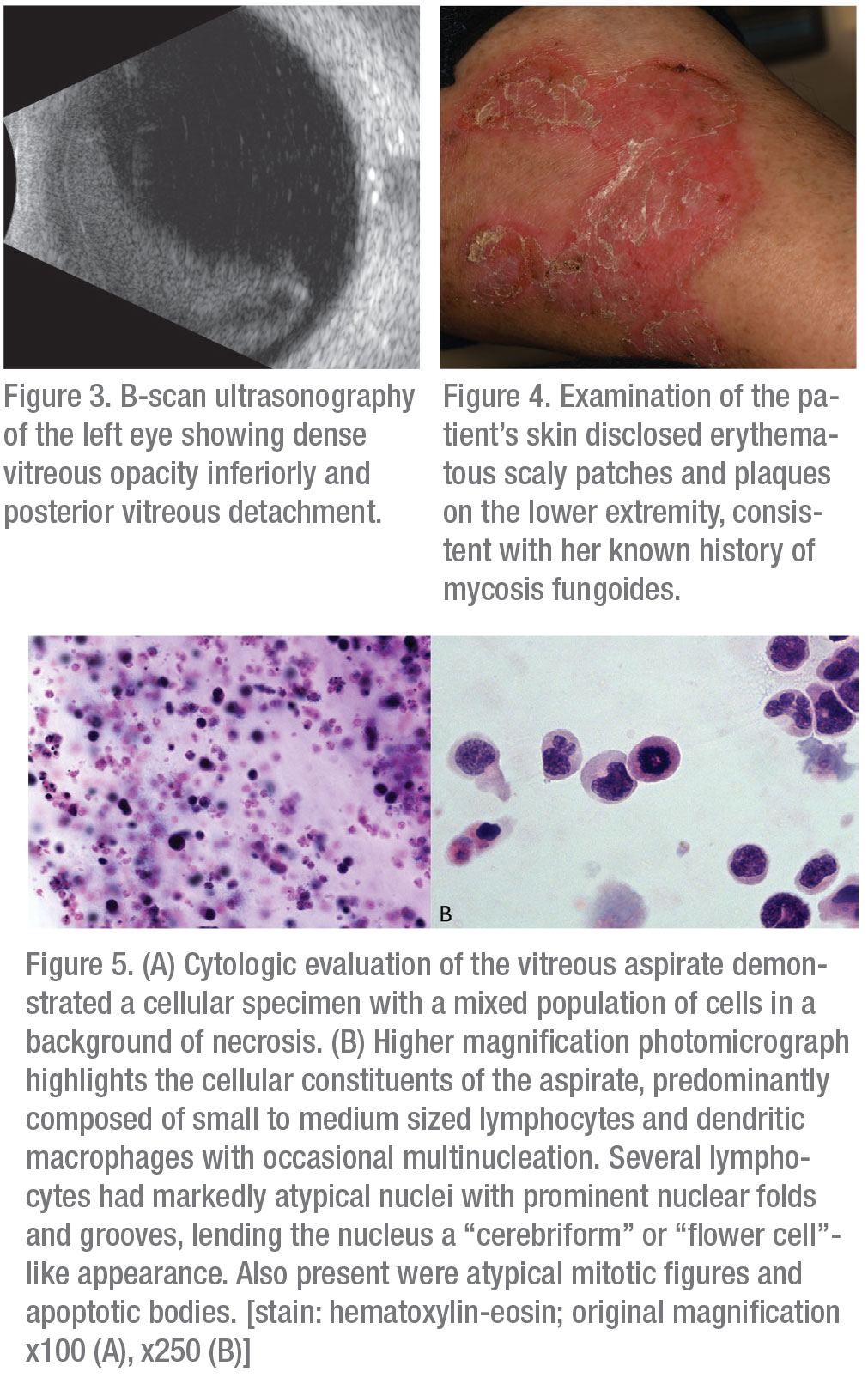

Serologic evaluation of the following were negative or non-reactive: HIV 1/2 antigen/antibody; Lyme IgG/IgM; Quantiferon Gold; Toxoplasma IgG/IgM; Bartonella henselae; and quintana IgG/IgM. FTA-ABS testing was equivocal; though given the patient’s low risk profile, it was interpreted as non-reactive. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 57 (reference range 0-29 mm/hour). Complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, ACE level, LDH, and muramidase level were all within normal limits. Optical coherence tomography revealed small sub-retinal pigment epithelial deposits in both eyes consistent with drusen (Figures 2A and B). B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated dense vitritis in the left eye, consistent with clinical examination (Figure 3). Skin evaluation disclosed pruritic, erythematous scaly patches and plaques on the patient’s lower legs, consistent with active mycosis fungoides (Figure 4).

|

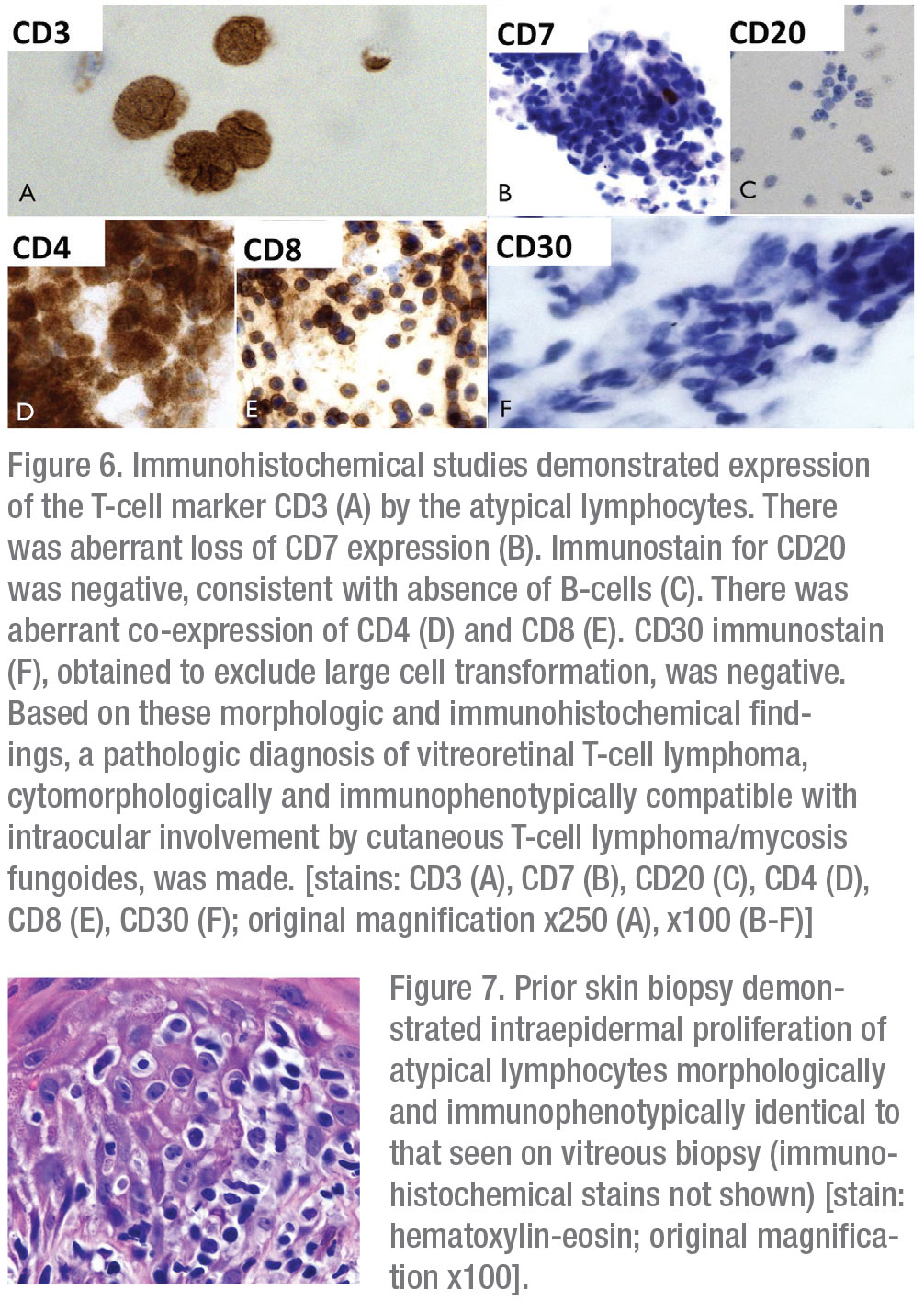

Given the patient’s age and important oncologic history, primary attention was directed toward evaluation for intraocular dissemination of systemic malignancy. The patient underwent therapeutic and diagnostic pars plana vitrectomy with vitreous biopsy. Cytopathologic examination of a vitreous specimen from the left eye revealed variably sized atypical lymphocytes with markedly folded, irregular nuclear contours, scant to abundant cytoplasm and frequent mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies (Figures 5A and B). Immunohistochemical staining revealed CD3 positivity and absence of CD20 expression. There was aberrant co-expression of CD4 and CD8 and loss of CD7 expression. There was no evidence of CD30+ transformed large cells (Figures 6A-F). Examination of skin-punch biopsy performed 12 years earlier revealed nearly identical morphologic and immunophenotypic features, confirming a diagnosis of vitreoretinal T-cell lymphoma arising from an MF variant of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) (Figure 7).

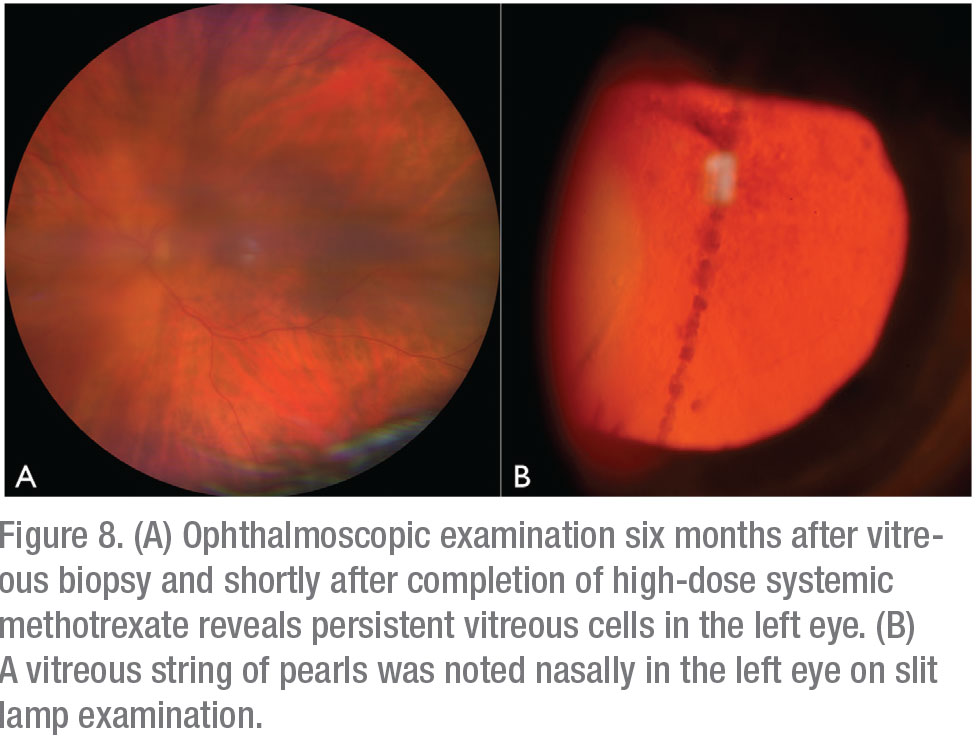

The patient underwent brain MRI, which demonstrated areas of T2 hyperintensity in multiple brain regions, suggestive of central nervous system lymphoma. Whole body PET-CT confirmed CNS uptake, but didn’t show visceral involvement. Peripheral blood flow cytometry was negative for circulating neoplastic T cells. Repeat ophthalmoscopic examination one month after vitrectomy revealed new vitreous cell in the right eye, in addition to persistent vitritis in the residual vitreous skirt of the left eye. She was referred to Medical Oncology and initiated on six cycles of high-dose systemic methotrexate for presumed CNS involvement by disseminated cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Four months later, after completion of systemic methotrexate therapy, the patient was noted to have increased vitritis in the left eye (Figures 8A and B). There was no evidence of lymphoma in the right eye. She received serial injections of intravitreal methotrexate (400 ug/0.1 ml) to the left eye with clearance of vitreous cells after three injections. Repeat brain MRI at eight months post-CNS diagnosis demonstrated a new, 3-cm lesion in the right basal ganglia. The patient elected to pursue hospice care and passed away from her disease approximately 10 months after initial ophthalmic presentation.

Discussion

Intraocular lymphoma can initially manifest in the eye itself, arise in the setting of prior primary CNS lymphoma, or less commonly can be a manifestation of disseminated systemic lymphoma.1 Dissemination of systemic lymphoma most frequently involves the uvea; vitreoretinal involvement is uncommon.1 Most intraocular lymphomas are of B-cell origin and intraocular involvement by T-cell lymphoma is exceedingly rare.2,3 A recent review of 29 cases of T-cell lymphoma with involvement of the eye found the mycosis fungoides-subtype of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma to be most frequent (27.6 percent).4

|

The cutaneous T-cell lymphomas comprise a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders characterized by predominant localization of neoplastic T cells to the skin, though visceral sites may become involved with disease progression. Mycosis fungoides, which accounts for 44 percent of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, typically follows an indolent course with five-year survival rates approaching 90 percent.5 Mycosis fungoides presents classically with pruritic erythematous cutaneous patches that, over time, can progress to infiltrative plaques and nodular tumors. Patients are typically older age (median age at diagnosis: 55 to 60), more frequently male and Caucasian.5 Clinical staging of mycosis fungoides is based on the following: extent of cutaneous disease; presence of lymph node and visceral involvement; and identification of circulating neoplastic cells in the blood. Treatment is stage-dependent, ranging from topical corticosteroid therapy and phototherapy for early stage mycosis fungoides (cutaneous patches or plaques only, stage IA to IIA) to the use of systemic therapy with immunomodulatory agents, such as interferon and oral retinoids; and chemotherapeutics, including methotrexate, for cases of refractory early-stage and more advanced disease (skin tumors greater than or equal to 1 cm, stage IIB to IVB).6

Ophthalmic manifestations of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma are rare. A comprehensive study of 2,155 patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma revealed ophthalmic abnormalities in fewer than 2 percent of them.7 These included cicatricial eyelid ectropion (0.8 percent), retinal infiltration (0.09 percent) and optic nerve involvement (0.05 percent).7 In a review of 29 cases of biopsy-confirmed disseminated T-cell lymphoma of the intraocular structures, the median age at intraocular diagnosis was 57 years. Intraocular manifestations were noted at a mean of 76 months following skin diagnosis.4 Eye findings on presentation included vitritis (66 percent) and non-granulomatous anterior uveitis (45 percent). Differentiating between T-cell and B-cell vitreoretinal lymphoma isn’t possible based on clinical eye examination alone; it requires biopsy with histopathology and immunohistochemistry.

|

Vitreoretinal T-cell lymphoma has the potential to masquerade as intraocular infection or inflammation. Hence, diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion. Findings on optical coherence tomography can include fine hyperreflective sub-retinal pigment epithelial deposits, corresponding to hyperautofluorescence on fundus autofluorescence imaging.8 While clinical examination and imaging studies can guide diagnosis, the gold standard remains cytopathologic examination of an intraocular sample, which can be obtained via vitreous aspiration or pars plana vitrectomy. Advantages of vitrectomy over needle biopsy include therapeutic potential to improve vision and maximization of the diagnostic yield.8,9 Nevertheless, non-diagnostic vitreous specimens aren’t uncommon and may necessitate additional sampling. Further, presence of reactive inflammatory cells, necrosis and cellular debris may complicate cytopathologic evaluation.8 In a retrospective case series of 33 eyes with suspected intraocular lymphoma that underwent vitrectomy, the positive predictive value of cytopathology was 100 percent and negative predictive value was just under 61 percent.10 These findings indicate that a negative vitreous specimen doesn’t exclude intraocular lymphoma and repeat sampling may be necessary.

Morphologically, neoplastic T cells appear as medium to large lymphoid cells with irregular nuclear contours and scant cytoplasm.8 Immunohistochemical studies reveal CD3 positivity and absence of CD20 staining. Molecular testing and flow cytometry can be used adjunctively to improve diagnostic accuracy. In cases of suspected disseminated lymphoma from known systemic (or extraocular) primary, morphologic, immunophenotypic and, when available, molecular genetic comparison of intraocular specimen to primary tumor, as in this case, may aid in confirming the final diagnosis. Subsequent MRI of the brain with or without cerebrospinal fluid sampling is recommended to assess for CNS involvement in confirmed cases of intraocular lymphoma.1

Given the rarity of disseminated vitreoretinal T-cell lymphoma, there are no guidelines for therapy. Most approaches are based on data from patients with primary vitreoretinal B-cell lymphoma. Radiation therapy, intravitreal chemotherapy and systemic chemotherapy, alone or in combination, have been described.11 Among patients with vitreoretinal B-cell lymphoma without concurrent CNS manifestations, development of CNS disease has been shown to occur at a similar frequency when comparing those receiving systemic treatment and those receiving intraocular treatment alone.11 Intravitreal injection of methotrexate is a common and effective treatment choice.11

In a series of 44 eyes with biopsy-proven vitreoretinal lymphoma (either B- or T-cell type), injection of intravitreal methotrexate achieved intraocular clearance of malignant cells following a mean of six injections; however patients are advised to undergo a full year of injections for a complete course.12 Toxicities were few, and included corneal epitheliopathy, cataract progression and neovascular glaucoma.12 More recently, use of intravitreal melphalan has been described as having the potential to achieve intraocular control with fewer injections.13 Despite the efficacy of intravitreal therapy, patients often succumb to the burden of CNS or systemic disease. Overall, prognosis is poor for patients with intraocular T-cell lymphoma with a mean survival of 21.7 months after intraocular diagnosis.2

In summary, a 79-year-old woman with a longstanding history of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma on systemic oral therapy presented with several months of progressive blurred vision and floaters in the left eye. Pars plana vitrectomy with vitreous biopsy demonstrated malignant T cells morphologically and immonophenotypically similar to those seen on skin biopsy 12 years earlier, confirming a diagnosis of vitreoretinal T-cell lymphoma arising from cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Subsequent imaging demonstrated CNS disease, and the patient was initiated on systemic chemotherapy with high-dose methotrexate. Although resolution of intraocular lymphoma was achieved with serial injections of intravitreal methotrexate, the patient succumbed to progressive CNS disease. REVIEW

1. Davis JL. Intraocular lymphoma: A clinical perspective. Eye (London, England) 2013;27:2:153-162.

2. Chaput F, Amer R, Baglivo E, et al. Intraocular T-cell lymphoma: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation. 2017;25:5:639-648.

3. Levasseur SD, Wittenberg LA, White VA. Vitreoretinal lymphoma: A 20-year review of incidence, clinical and cytologic features, treatment, and outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmology 2013;131:1:50-55.

4. Levy-Clarke GA, Greenman D, Sieving PC, et al. Ophthalmic manifestations, cytology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular analysis of intraocular metastatic T-cell lymphoma: Report of a case and review of the literature. Survey of Ophthalmology 2008;53:3:285-295.

5. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome): Part I. Diagnosis: Clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol 2014;70:2:205 e201-216; quiz 221-202.

6. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome): Part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:2:223 e221-217; quiz 240-222.

7. Cook BE, Jr., Bartley GB, Pittelkow MR. Ophthalmic abnormalities in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 1998;96:309-324; discussion 324-307.

8.Tang LJ, Gu CL, Zhang P. Intraocular lymphoma. International Journal of Ophthalmology 2017;10:8:1301-1307.

9. Mudhar HS, Sheard R. Diagnostic cellular yield is superior with full pars plana vitrectomy compared with core vitreous biopsy. Eye (London, England) 2013;27:1:50-55.

10. Davis JL, Miller DM, Ruiz P. Diagnostic testing of vitrectomy specimens. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:5:822-829.

11. Riemens A, Bromberg J, Touitou V, et al. Treatment strategies in primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A 17-center European collaborative study. JAMA Ophthalmology 2015;133:2:191-197.

12. Frenkel S, Hendler K, Siegal T, Shalom E, Pe’er J. Intravitreal methotrexate for treating vitreoretinal lymphoma: 10 years of experience. The British Journal of ophthalmology 2008;92:3:383-388.

13. Shields CL, Sioufi K, Mashayekhi A, Shields JA. Intravitreal melphalan for treatment of primary vitreoretinal lymphoma: A new indication for an old drug. JAMA Ophthalmology 2017;135:7:815.