As toric intraocular lenses become more popular, accurate alignment of the lens inside the eye remains a key concern. “For every degree of misalignment, about 3 percent of the lens cylinder power is lost,” notes Soosan Jacob, MD, a senior consultant ophthalmologist at Dr. Amar Agarwal’s Eye Hospital in Chennai, India. “If it’s 30 degrees off, it’s a total loss—the lens will have zero effect. If you’re more than 30 degrees off, you’re actually increasing the patient’s postoperative astigmatism.”

Accurate alignment is a function of several factors, including accurate measurement of the astigmatic axis, accurately locating that axis in the eye, placing the lens correctly and preventing or correcting any postoperative misalignment. Here, four experienced surgeons share their advice on getting toric IOL alignment right.

Finding the Axis: A New Factor

Identifying the axis, even in cases of regular astigmatism, is not as straightforward as it seems. “There’s variability in everything,” notes James A. Davison, MD, FACS, who practices at the Wolfe Eye Clinic in Marshalltown and West Des Moines, Iowa. “Some people have zero diopters of keratometric astigmatism but still have some significant cylinder in their refraction. Some have keratometric astigmatism, but they don’t choose cylinder correction in the manifest refraction.”

Reflecting that complexity, Dr. Davison, like some of his colleagues, noted that something unexplained was happening with some of his toric patients. “We found patients were sometimes coming out slightly undercorrected or overcorrected, for no obvious reason,” he says. “We realized that most keratometry and topography are just based on the anterior reflection of the anterior surface of the cornea. However, the Pentacam has a measurement called ‘total corneal refractive power’ that also takes into account the posterior surface of the cornea. We found that this produced a slightly different measurement. For example, the sagittal anterior reflection measurement from the Pentacam might indicate that we should use a T4 lens, but the total corneal refractive power might back it off to a T3 lens.

“So we began checking in the clinic to see whether the outcomes were better if the correction was based on the Pentacam’s total corneal refractive power measurement, and how it compared to the outcomes using keratometry from the IOLMaster and Lenstar,” he continues. “We haven’t analyzed all of our data yet, but our impression is that we’re getting better results using the total corneal refractive power measurement for with-the-rule, against-the-rule, and obliquely oriented astigmatism.”

A similar experience led Douglas D. Koch, MD, professor of ophthalmology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, to uncover some key factors that can affect the outcome when implanting a toric IOL—both in the near and long term. “I had treated a patient who had with-the-rule astigmatism, and my measurements indicated that he should have come out a tiny bit undercorrected,” he says. “Instead, he was overcorrected. At the same time, I treated another patient who started out with against-the-rule astigmatism; if anything, that patient should have ended up slightly overcorrected, but instead she was undercorrected. There was no obvious explanation.

“Prior to seeing those patients, I had started a study along with Li Wang and Mitchell Weikert in our group, looking at posterior corneal astigmatism,” he continues. “We were curious to find out whether this was an issue. We weren’t aware that the literature had already demonstrated that there was some astigmatism there. Our own research found a significant amount of posterior corneal astigmatism, and it has indeed turned out to be significant in our clinical use of toric lenses.

“We found that the posterior cornea is steeper vertically in almost everybody,” he says. “Because it’s a minus lens, it creates refractive power horizontally, or against-the-rule refractive power at 180 degrees. So the with-the-rule patient who was overcorrected had posterior corneal astigmatism that was adding to his against-the-rule refractive power. That’s why he ended up overcorrected. And the patient who had the against-the-rule astigmatism had additional against-the-rule on the back, which is why she came out undercorrected.”

Constructing a Nomogram

“After realizing this I began to look at other patients and found I was seeing this all the time,” Dr. Koch continues.

“Using the data from our Galilei Scheimpflug analyzer, we found an average of about a half diopter of posterior astigmatism when patients had with-the-rule on the front; and about 0.3 D when they had against-the-rule on the front. It does vary from patient to patient, so measuring it would be ideal. However, using those numbers, we were able to construct a basic nomogram for modifying the toric IOL selection to accommodate the posterior astigmatism.” (Dr. Davison notes that his use of the total corneal refractive power from the Pentacam produces a modification that appears similar to Dr. Koch’s posterior corneal astigmatism nomogram adjustment.)

| ||||||

Dr. Koch says he soon found another factor worth taking into account. “I came across a fascinating paper by Ken Hayashi, MD, in the American Journal of Ophthalmology, in which patients were followed for 10 years,” he says. “His team followed two groups: One had no surgery, while the other had 3-mm clear corneal temporal incisions. Despite having temporal incisions, the latter patients gradually shifted toward against-the-rule astigmatism over 10 years by about 3/8 D, just like the unoperated eyes did.1

“What we’ve learned is that even though cataract surgery may be ‘weakening’ the cornea temporally, it doesn’t protect you against the gradual against-the-rule shift that corneas undergo,” he explains. “So, when deciding how to proceed with a toric IOL, my thought is that we should leave patients a little bit of with-the-rule so they can still have good vision over the years as they gradually shift against-the-rule.”

Dr. Koch has constructed a nomogram that takes into account the average posterior corneal astigmatism in the with-the-rule and against-the-rule groups. (See p. 21) It also takes into account the need to leave these patients with a little bit of with-the-rule astigmatism to compensate for the gradual against-the-rule shift caused by aging. “Of course, you may vary how you choose to apply the nomogram according to the patient’s age and other factors,” he says. “For example, in my experience most patients who have oblique astigmatism are in that progressive march from with-the-rule to against-the-rule. For those patients I usually attempt to correct the astigmatism fully, but I target the correction about 5 degrees on the against-the-rule side, so it gives them a little time as they continue to shift.”

| |||||

Dr. Koch says it’s still early in the refinement of the nomogram, although he has data that support it. “We have the data we gathered by measuring posterior corneal surfaces in virgin eyes, and now we have data on 41 eyes that have had surgery,” he says. “The nomogram nails it. It’s pretty amazing that we’ve been using toric lenses for several years, and we’re just now figuring this out.”

He notes that the manufacturers are aware of this issue, and they’re in a bit of a dilemma. “The FDA understandably doesn’t want manufacturers sending out nomograms that haven’t been validated with FDA data,” he says. “But I know that at least two manufacturers have looked at their data, and said, ‘Oh my goodness—there it is.’ ”

Marking Freehand

Marking the eye is a potential source of error, for many reasons. Tools to increase accuracy are proliferating, as are high-tech approaches that hope to circumvent the need to make a mark altogether. Nevertheless, like many surgeons, Dr. Davison prefers to mark the eye freehand. His preference is to make a mark at 6 o’clock on the conjunctival limbus using a fine-tip marker. “The fine-tip marker makes a pretty small dot,” he notes, “in contrast to a medium tip marker that can make a dot that’s 10 degrees wide, or a small tip, which makes a dot that’s probably about three degrees wide.

“In surgery we put the speculum in and put some more drops in,” he continues. “Then we line the axis marker up with the 6:00 dot and make sure everything looks perfectly spaced around the limbus, so we’re not eccentric. Then we take the axis marker and mark the intended axis. Once that’s done and everything looks perfect, I dry the cornea a little at the periphery and I take a Weck-Cel sponge with ink on it and reinforce the intended axis mark to ensure it won’t wash away. After that it’s just a matter of putting in the lens and getting it to the right spot.

“Once the lens is in, I get all of the viscoelastic out from behind and in front of the lens,” he says. “Then I rotate the lens so it’s 10 to 15 degrees from the intended alignment, reinflate the eye, hydrate the incision and try to get everything looking nice and normal. I can usually go in with BSS on a 30-ga. cannula and move the lens to the final position. If too much fluid leaks out of the incision using the 30-ga. cannula, I can go in and do the rotation with the silicone irrigation/aspiration tip. You can actually suck on the anterior IOL optic with it, like a little plunger, and rotate the implant just like dialing an old-fashioned rotary telephone dial.”

Tools for Better Marking

One method of freehand marking some surgeons prefer is putting two marks across from each other on the horizontal axis. However, Dr. Jacob notes that this is less than ideal.

“It’s difficult to put the marks exactly 180 degrees apart,” she points out. “When the patient is lying down in the OR you may realize that your marks are not actually 180 degrees apart. Now you’re left wondering which of the marks is closer to the axis—and it’s likely that both of them are a bit off.”

|

Dr. Jacob says she prefers to use one of the currently available devices that help ensure the correct placement of horizontal reference marks. “Several markers have a bubble level,” she explains. “When the air bubble is exactly in the center of the two marks on the chamber, you know that the marker is horizontally aligned. You ink the marker and gently apply it to the patient’s eye while the patient is looking straight ahead, making sure the bubble shows the marker is horizontal. I use a drop of topical anesthetic and put a speculum on the eye; that allows me to concentrate on the bubble level without having to worry about keeping the patient’s eye open.

“Sometimes using the bubble level is difficult because you have to keep an eye on the bubble while also looking at the limbus,” she admits. “You don’t want to cause a corneal epithelial abrasion while you’re managing all this. However, some devices make this easier. ASICO now offers the Akahoshi electronic marker, which has three lights—red green and orange. When the marker is horizontal, the light is green; the other colors tell you which way you’re tilted if you’re not horizontal. The device can also provide an auditory cue when the marker is horizontal, so you don’t have to look away from the eye to know when the orientation is correct. Most markers, including this one, come in two versions: One just makes the horizontal reference marks; the other allows you to directly mark the target axis for the IOL.”

Robert H. Osher, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Cincinnati, is a leading advocate of finding better ways to align toric lenses. “I dislike approaches that use ink to mark the eye,” he says. “The ink diffuses and the results are inaccurate.” He notes that one of the newest alternatives to marking the eye with ink is the Wet-Field Osher ThermoDot Marker from Beaver-Visitec. (He has no financial interest.) “The ThermoDot is a tiny dot created by a specially designed wet-field cautery tip, making an indelible mark on the target meridian,” he explains. “So instead of using ink and having the mark diffuse or disappear, the tiny dot remains throughout the case. The device was released at this year’s Academy of Ophthalmology meeting.” (For more information, visit

beaver-visitec.com/products/electrosurgery.cfm.)

The High-tech Approach

Dr. Osher has also worked with three high-tech tools designed to aid alignment, currently in different stages of development. “The first is iris imaging,” he says. “I refer to this as fingerprinting. We take a photo of the iris, use software to overlay a protractor onto the image and then either inject it into the microscope view or print it. This approach is a little bit time-consuming, but it gives you extremely accurate orientation.”

Dr. Osher notes that this method requires following a few basic principles. “Initially I tried orienting the lens by using the limbal vessels as landmarks,” he says. “However, that doesn’t work well when you dilate the pupils with neosynephrin because the vessels shrink up. In fact, some of the vessels dilate if you use preoperative topical antibiotics, so matching vessels can be challenging. Moreover, you can’t have a picture of an undilated pupil and expect to get yourself well-oriented once the pupil is dilated in surgery. So, the image I take is a high-res photo when the patient is dilated during the original examination. Once I have that, there are many landmarks that make it very easy to get accurately oriented—crypts, nevi, unique patterns of stroma, Brushfield spots and all kinds of dark and light areas in the iris.”

Dr. Osher points out that using this approach requires a high-resolution camera and appropriate software. “I know of at least three companies that are doing this,” he says. “The initial company I worked with was Micron Imaging. They were geared up to introduce this technology, but the recent flood in Nashville wiped them out. Haag Streit has just introduced a similar system, the Osher toric alignment system. [Dr. Osher has no financial interest.] And Tracey Technologies is developing a camera that can do the same thing, as well as import the information into the Hoya toric calculator. Using the iris in this way is a simple and accurate way to ensure accurate toric alignment.

“The second approach is limbal registration,” he continues. “This captures an image of the limbus when the patient is upright and looking into the distance, and then allows you to overlay the captured image onto the live image in the OR. The software superimposes them and tells you exactly where to rotate the lens to have it be accurately oriented.”

|

Intraoperative Aberrometry

Dr. Osher says the third and most sophisticated option is intraoperative visual field aberrometry. “Most surgeons are aware of WaveTec’s ORA system, which uses Talbot-Moiré-based interferometry technology,” notes Dr. Osher. “That system has been the leader in intraoperative wavefront aberrometry. However, that is a static system; you take a picture, then rotate the IOL.

“I’ve worked with a newer system from Clarity Medical Systems, called Holos IntraOp,” he continues. “Holos does real-time dynamic wavefront aberrometry scanning. You don’t need any preoperative information. It literally measures the eye’s toricity on the table, and as you rotate the lens, you see what effect the rotation has in real time. When the image indicates that cylinder is no longer present, you’ve neutralized all of the astigmatism and you stop rotating. It’s accurate to within one degree. And it has other advantages, such as confirming emmetropia, which is very important. So far, the Clarity system is still not available, although a prototype was shown at the 2012 American Academy of Ophthalmology meeting in Chicago.

“Unfortunately, right now there’s not a huge incentive for surgeons to invest in this kind of new technology to address astigmatism,” he adds. “Because let’s face it: If you take the cataract out, the patient should see better. If you also correct the preop near- or far-sightedness, the patient will see better than ever. If you then correct the astigmatism, the patient will see even better still, but that’s the icing on the cake. Nevertheless, cylinder is a component of the pseudophakic refractive error and, if the holy grail is emmetropia, we should attempt to reduce or eliminate preexisting astigmatism, period.”

Of course, not everyone is sold on the value of the intraoperative approach—at least in its current (static) form. “If you’re basing your orientation on really accurate readings, I don’t think an aberrometer will change the axis that much,” says Dr. Davison. “It’s the same for the spherical component. The data I’ve seen says that about 6 percent of intraoperative aberrometry patients still end up with 0.75 D or more or spherical equivalent residual refractive error after surgery. Without using aberrometers, we have 7 percent of our patients with 0.75 D or more of residual spherical equivalent refractive error after surgery. Of course, that technology will get better. If we can get it down to 1 percent of patients with that much residual spherical equivalent refractive error, that would be a better argument for adopting the technology.”

Dr. Osher adds that a simpler tool like the ThermoDot Marker is valuable, even if you have access to advanced technology such as the ORA or Holos system, or iris or limbal registration. “Relying solely on one technology, no matter how advanced, is like flying with one propeller,” he says. “I’m OK with that, but I still like to have my marks as a fallback. For example, I had a case recently in which the ink mark that my nurses always put on at 6:00 diffused; I couldn’t tell where the original mark had been. At the same time, I couldn’t use limbal registration because the anesthetic that was given dissected under and raised the conjunctiva, totally distorting the anatomy. Having an indelible mark is an important safeguard; if something goes wrong, you still have a way to proceed. When I’m orienting a toric lens, I’m not willing to depend on one technology, any more than I’m willing to depend on a single preop measurement of K.”

Measuring & Marking Pearls

These strategies can help maximize toric outcomes:

• Use multiple measurements when getting the K value. “I conducted a large study with Dr. Andrew Browne,” says Dr. Osher. “We discovered that every technology will yield a certain number of outliers. In my office we get a manual K and then measure keratometry with five other technologies. (I know that no one else is that obsessive about it.) Any given technology will produce outliers; so the more measurements you have, the more likely it is that this ‘melding’ strategy will produce accurate outcomes.”

“At least one of the devices you use should be a topographer,” adds Dr. Koch. “We use the Lenstar, IOLMaster and two topographers. With the topographers we look at the overall appearance of the map, independent of the SimK, to see where the image shows the overall astigmatism to be. That should match what we’ve found with the other measurements. If not, we know there’s a problem.”

• Look at the average topographer measurements over the central 3 or 4 mm. “In most devices, SimK represents just a few spots at the 3-mm zone,” Dr. Koch points out. “The average measurement of astigmatism over the entire central 3 or 4 mm is a more valuable number. Ideally, it should be in agreement with the Lenstar or IOLMaster reading.”

• Consider what the refraction shows. “If it’s a good refraction and the patient has good enough vision that it’s meaningful, it often gives me some clues about the against-the-rule astigmatism that may be present on the posterior corneal surface,” says Dr. Koch.

• Check all of the data points. “There will always be mystery cases,” notes Dr. Koch. “I saw a patient who had 2 D of with-the-rule astigmatism in her cornea, and 1 D of against-the-rule in her glasses. I didn’t do any astigmatism correction during her cataract surgery, and she ended up 20/20 uncorrected. She had some posterior corneal astigmatism, and she may have had some lenticular astigmatism as well, to create that big a disparity between the cornea and the lens. So looking at all of the data points is important.”

• Proceed with caution if the patient has anterior basement corneal dystrophy. “These eyes can produce an unusual topographical map,” notes Dr. Davison. “Sometimes it’s hard to know exactly where to orient the lens. The other thing is, if the patient’s corneal epithelium changes from day to day, sometimes the patient gets better performance on one day than another day. Their expectations may be so high that they’ll be disappointed by fluctuating vision, which, of course, they would also have with a non-toric IOL.”

• Don’t wait to record the results of your measurements. “Enter the results of your testing into the record right away to avoid mistakes,” says Dr. Davison. “We designed a template for our EHR system for this purpose. While we’re in the room with the patient and getting the Pentacam, IOLMaster and Lenstar readings, we immediately enter them into our template. The nurse and I both double-check the numbers, and they’re checked again later, before surgery.”

• Base the cylinder correction on the corneal astigmatism, not the refractive astigmatism. “When the patient has cataract surgery, any amount of lenticular astigmatism that was there will be removed,” Dr. Jacob points out. “Only the corneal astigmatism will be left behind, so that’s the thing you should treat.”

• Know your specific surgeon-induced astigmatism factor. “It’s important to personalize your SIA, so you can put this number into the toric IOL calculator,” says Dr. Jacob.

• Be wary of leaving the patient with against-the-rule astigmatism. “Patients generally tolerate with-the-rule astigmatism better than against-the-rule astigmatism,” says Dr. Jacob. “So, with with-the-rule you have to be very careful about how much you’re treating. Overcorrecting it can create some against-the-rule astigmatism, which the patient won’t tolerate.”

• Always check your marks after you make them. “Don’t assume that your marks are right at 180 or 90 degrees,” says Dr. Koch.

• Make sure the patient is marked before using a retrobulbar block. “Make sure everyone in the OR knows that the patient is receiving a toric IOL so that blocking is not done until after the axis has been marked,” says Dr. Jacob. “If the patient is blocked before you’re able to mark the axis, you won’t be able to mark it accurately.”

|

Pearls for the OR

• Bring the toric axis printout with you into the OR and turn it upside down. “All the toric IOL manufacturers give you a printout from calculators that are available on line,” Dr. Jacob points out. “The printout shows the intended axis of placement and the site for the clear corneal incision, in order to take your surgically induced astigmatism into account. Turning the printout upside down makes these marks match the view you have of the eye, which helps to avoid mistakes in alignment.”

• When the eye is very long, consider making the Descemet’s entry portion of the incision a little more central so that its total length is 2 mm. “This makes it easier to avoid overinflating the eye, so it seals nicely with normal IOP,” says Dr. Davison.

• Consider creating a slightly smaller capsulorhexis. “If you make it 5 mm, that helps to prevent the edge of the optic from popping out of the bag, or the IOL rotating excessively,” says Dr. Jacob. “It’s good to have overlap of the capsulorhexis all around the optic.”

• Don’t base your capsulotomy size on the size of the pupil. “When working on a bigger eye, surgeons have a tendency to make a bigger capsulotomy,” notes Dr. Davison. “But if the capsulotomy is too big, the lens is more likely to rotate after surgery.”

Dr. Davison cites a study he did with New Mexico surgeon Art Weinstein, MD. “We showed that about 3.4 percent of the lenses between 6 and 10.5 D actually rotated enough after surgery that they had to be reoriented,” he says. “From 11 to 15.5 D it was 1.4 percent; for 16 D to 20.5 it was about 0.5 percent. No eyes over 20.5 D had to be reoriented. It appears that part of the reason for this might be that there’s no real template to use to get the right size capsulorhexis, so you just make it to fit inside the pupil. That’s a problem, especially in big eyes. The bigger capsulorhexis allows the toric lens to rotate more easily.

“The problem is, if you deliberately try to make the capsulotomy smaller, you might make it smaller than 4.6 mm,” he says. “Then you’ll have a higher tendency for capsular contraction and anterior capsule phymosis, which you don’t want either. So I think there’s a sweet spot there for the high myope; you don’t want the diameter smaller or bigger than 4.6 mm.”

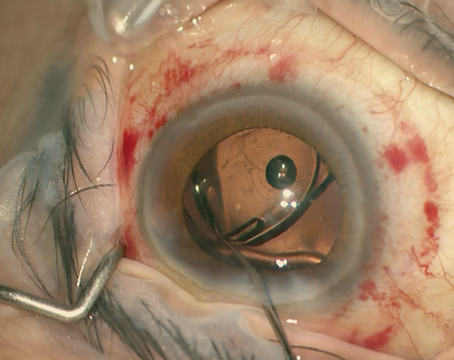

Dr. Davison notes that one way around this is to make the capsulotomy with a femtosecond laser. (See photo, above.) “We’ve had a femto cataract laser since spring,” he notes. “If you make it part of your astigmatism package, you can make the capsulotomy exactly 4.6 mm, so it embraces the toric IOL perfectly. That should minimize the likelihood that you’ll have to reorient the lens postop.

“The most obvious way to see whether your capsulorhexis is the right size is to check it against the three little dots on the toric lens,” he adds. “The three little dots on the toric lens are at 0.2, 0.45 and 0.7 mm from the optic edge. So if the capsulorhexis is 4.6 mm—what I think is the perfect size for a high myope—the internal little dot on the toric lens should touch the edge of the capsulotomy when you’re done. I used to have to reorient 1.2 percent of these cases postop. Since paying attention to these details, my rate has dropped to 0.6 percent.”

• Expect the lens to rotate a little when you remove the viscoelastic. “When rotating the lens, stop about 10 to 30 degrees short of the intended axis,” says Dr. Jacobs. “While removing the viscoelastic the IOL will rotate a little bit more. If you put it exactly on the mark before removing the viscoelastic, it’s possible that the IOL will move during the viscoelastic removal, causing you to overshoot the intended axis. Trying to rotate it back in the opposite direction, counter-clockwise, doesn’t work because it doesn’t move well in that direction. If you overshoot, you’ll have to rotate 180 degrees.”

• Be especially careful when the lens sits vertically, standing on its inferior haptic. “A vertically oriented lens is like standing a pencil straight up on your desk,” notes Dr. Davison. “It wants to tip over. If you stand a lens up inside the eye to manage with-the-rule astigmatism, it eventually wants to be oriented not at 90 but 180 degrees. That’s what happens to some high myopes; the lens just falls off-axis, like a pencil tipping over. So it’s important to do everything you can to prevent the lens from rotating in this situation.” Dr. Davison adds that in his study of postop lens rotation (mentioned above), almost all of the cases that required reorientation were with-the-rule astigmatism where the IOL was oriented vertically.

• When using iris retractors, align the lens before removing the retractors. “When you have a patient with a small pupil, you may have to use iris retractors to make the pupil bigger,” notes Dr. Davison. “The usual order toward the end of the surgery is to take the iris retractors out and then take the viscoelastic out, but if you do that in this situation, the pupil comes down and you can’t align the lens. So, you have to align it before you take iris retractors out. Go ahead and remove the viscoelastic, do some stromal hydration to the incision, then do your adjusting maneuvers so the lens lines up. Then you can take the retractors out.

“When you’re doing this you might lose a little bit of anterior chamber depth,” he adds, “because you still have some leakage around where the iris retractors are. If so, you may have to reinflate the eye a little bit.”

• Make sure you do a thorough viscoelastic removal. “One of the major causes of postoperative IOL rotation is retained viscoelastic within the bag,” notes Dr. Jacob, “So the surgeon should gently lift the edge of the IOL optic with the tip of the I/A probe and remove the viscoelastic left behind the optic of the IOL.”

• Once you’ve removed most of the viscoelastic, gently tap down on the lens to help it adhere to the posterior capsule. “The tacky nature of the lens surface helps it adhere to the posterior capsule, preventing further rotation,” says Dr. Jacob.

• Don’t overinflate the bag. “At the end of surgery most surgeons instill balanced salt solution into the anterior chamber to maintain IOP,” notes Dr. Jacob. “But if you overinflate the anterior chamber with BSS, the BSS goes behind the IOL into the space between the IOL optic and the posterior capsule, which can increase the tendency for the IOL to rotate.”

• Consider putting air rather than BSS into the anterior chamber at the end of surgery. Dr. Jacob prefers this option. “The air forms a bubble that pushes the optic of the IOL backward, helping to prevent rotation,” she explains. “It also prevents overinflation of the bag because it doesn’t go behind the optic, unlike BSS. In addition, it acts as an internal seal for the corneal incision and decreases the chances of wound leak, endophthalmitis or a shallow anterior chamber. The trade-off is that the patient won’t have good vision immediately, but I believe the benefits are worth the trade-off.”

• If you need to reorient a lens, try to wait about three weeks. “Sometimes that’s hard, because patients may have a lot of cylinder for those three weeks,” says Dr. Davison. “But waiting allows the early capsule fibrosis and shrinkage to start, making things a little contracted and a little bit sticky. The capsular bag starts to adhere to the IOL haptics. Then, when you go in and rotate it again, it’s more likely to stay where it’s supposed to.

“There are a lot of ways to do the rotation at that point,” he continues. “I’ve heard of people trying to do it at the slit lamp, but I think that’s risky. I go back to surgery and use the original incision. I put Provisc (sodium hyaluronate 1%) on the anterior surface of the lens and fill the anterior chamber. That will let you loosen the adhesions that have formed by three weeks. Then you just rotate the lens to the proper position and remove the viscoelastic. In my experience, the lenses stay in place after this.”

• If you have to reorient a lens, get help at

astigmatismfix.com. “This site offers a formula created by John Berdahl and David Hardten,” says Dr. Davison. “If a toric lens has moved, you enter the current refraction and where the lens is oriented, and the formula will tell you the correct axis the lens should be left at after reorientation.”

Target: The Best Possible Vision

“I think toric lenses are vastly underutilized,” says Dr. Osher. “No ophthalmologist in the office would identify a significant amount of astigmatism and ignore it. Everyone would at least give the patient a pair of glasses that corrects both the spherical refractive error and the astigmatism. We have the same technology in surgery, so we should always offer the patient correction of his astigmatism in addition to the correction of the spherical error. I believe that this will become the new standard of care, and toric lenses are a key part of that.

“I’m absolutely sure that the future will bring us more sophisticated—and unfortunately, more expensive—technologies that nail the target meridian,” he continues. “The only way the full potential of advanced technology lenses such as torics or multifocals will be reached is to have either the diagnostic, preoperative technology or the intraoperative technology to confirm emmetropia on the spherical side, and make sure the axis is dead-on on the cylindrical side of the equation. This should be our noble goal, and I believe it’s within our reach.” REVIEW

1. Hayashi K, Hirata A, Manabe S, Hayashi H. Long-Term Change in Corneal Astigmatism After Sutureless Cataract Surgery. Amer J Opthal 2011;151:4:858-865.