Certainly one of the keys to success is careful measurement and planning—and a thorough knowledge of your own statistical track record with implanting these lenses. That knowledge can act as a guide to choosing how to proceed under any given set of circumstances. “If you can’t deliver a perfectly emmetropic eye at the end of surgery, you have no business implanting a multifocal optic IOL,” notes Robert M. Kershner, MD, MS, FACS, professor and chairman of the department of Ophthalmic Medical Technology at Palm Beach State College, and president and CEO of Eye Laser Consulting in Palm Beach Gardens, Fla. “These lenses are not very forgiving; there are a number of surgical steps the surgeon has to pay attention to before selecting these advanced optic designs.

“First and foremost, you have to do everything in your power to maximize the optical result,” he says. “The step where you’re most likely to err is in your preop planning. Preoperative biometry and lens selection require the surgeon to know his or her own stats and data points in order to achieve a high level of accuracy. In reality, the outcome of multifocal surgery is determined before the surgery rather than during the surgery. If you can execute what you’ve planned to do and obtain the predicted result, you’ll have a happy patient.”

Preexisting Conditions

Richard Mackool, MD, PC, director of the Mackool Eye Institute and Laser Center and senior attending surgeon at the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary, says the most common avoidable error that surgeons make is failing to detect a pre-existing condition such as corneal epithelial or endothelial dystrophy. “A careful slit-lamp exam is required to detect them,” he notes. “It’s not that this is a frequent mistake, but of those that are made, this seems to be number one.

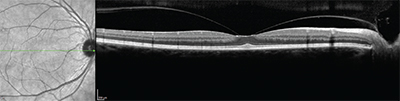

|

“On the other hand, if you have reason to suspect that there might be an epiretinal membrane, such as a questionable retinal exam or a disparity between the measured acuity and the density of the cataract, then by all means proceed and do a macular OCT preop,” he says. “This is important, because if you put in a multifocal lens and later discover that there was a preexisting epiretinal membrane, and the patient is not happy with his postop acuity, the waters are muddied. You won’t know whether the problem is being caused by the multifocal IOL, the epiretinal membrane or both.”

R. Bruce Wallace III, MD, FACS, founder and medical director of Wallace Eye Surgery in Alexandria, La., and clinical professor of ophthalmology at Louisiana State University and Tulane Schools of Medicine in New Orleans, agrees that preexisting conditions must be addressed, including dry eye. (Dr. Wallace has worked with multifocal IOLs since the first commercially available model—originally manufactured by the 3M Company—appeared.) “We have to treat the dry eye preoperatively and explain to these patients that they may need more intensive meds postop for quite a few months, because preservatives in the drops exacerbate preexisting dry eye,” he says. “That can really affect multifocal vision.”

Dr. Mackool notes that any symptoms like distorted or wavy vision are a clear tipoff that something is wrong. “You probably won’t put a multifocal IOL in that patient, no matter what,” he says. “In essence, anything that would lower the patient’s expected postoperative acuity and contrast sensitivity is a potential contraindication. Not necessarily an absolute contraindication, but potentially so.”

He adds that new multifocal lenses in the pipeline may alleviate these concerns. “The ReSTOR 2.5, which will probably be available in the United States in the next three to six months, provides distance acuity that is essentially the same as an aspheric monofocal lens,” he says. “Studies of the lens’s modulation transfer function show it to be virtually indistinguishable from an aspheric monofocal in this regard. So patients who would suffer from the loss of some contrast sensitivity associated with multifocal lenses would very likely do fine with this new lens.”

Working with Astigmatism

“Correcting astigmatism is obviously critical to getting a great outcome with these patients,” notes Dr. Wallace. “I’ve developed limbal relaxing incision instruments for Bausch + Lomb and Duckworth and Kent, and we spend a fair amount of time teaching surgeons to correct astigmatism using LRIs. Of course, the advent of femtosecond lasers has triggered a resurgence in interest in astigmatic keratotomy.

“In our experience, 2 D or less is a good limit for the amount of regular astigmatism correctable using LRIs,” he continues. “If the patient is starting off with more than 2 D of astigmatism we can still implant a multifocal, but the expectation level of the patient has to be lowered. Yes, you can always touch up some of these patients with LASIK if the outcome isn’t ideal, but that’s expensive. It’s better to let a patient with more than 2 D of astigmatism know that he or she is just not as good a candidate.”

Dr. Wallace notes that special attention may be required if the Ks and corneal topography don’t match up very well. “In those circumstances we will sometimes defer the LRIs until we see what the postop refraction in the first eye looks like,” he explains. “That will tell us what to do for both eyes. If we determine that the eye still needs some astigmatic correction, we’ll plan on doing LRIs in both eyes during the second eye’s surgery. We prep both eyes preoperatively; once we’re finished with the cataract surgery and I’ve done the LRIs on the second eye, I reach over and put a lid speculum in the first eye, move the microscope over and take care of that eye as well. We’ve been doing this for years, and it’s worked out quite well.”

Irregular astigmatism is generally considered a contraindication for implanting a multifocal lens. “If the patient has irregular astigmatism before surgery, I think you’re ill-advised to implant a multifocal optic,” says Dr. Kershner. “You’re not going to be able to control the refractive outcome. So if you cannot create a spherical cornea, you should set your postoperative goals to achieve functionality with another lens choice. Of course, if the patient ends up with irregular astigmatism that was not there before surgery, you must set out to correct the error. Find out where you went wrong and undo the damage. In most cases the error was present before the surgery, and was either missed in the preoperative workup, or made worse with an unrealistic surgical plan.”

Both Robert T. Crotty, OD, clinical director of Wallace Eye Surgery, and his wife have had multifocal implants in their own eyes. Dr. Crotty notes that at Wallace Eye Surgery both preoperative corneal topography and WaveScan aberrometry are done on all multifocal candidates. “We’re looking for increases in corneal aberration such as coma or astigmatism,” he explains. “Some studies have reported that corneal coma values greater than 0.32 µm may result in increased dysphotopsia with the use of diffractive multifocal IOLs. In general, irregular astigmatism often makes the quality of postoperative vision unpredictable. We don’t consider a patient who is demonstrating significant amounts of irregular astigmatism to be a candidate for a multifocal IOL.”

Previous Refractive Surgery

An increasing number of patients who are interested in multifocal implants have had prior LASIK, PRK or RK. This presents a number of challenges. “Caution should be taken with patients who have had previous refractive surgery and are considering multifocal IOLs,” says Dr. Crotty. “We’ve had a few cases of patients with previous radial keratotomy where we have implanted an accommodative intraocular lens with good success. We do believe that patients who have undergone refractive surgery, such as LASIK, PRK or RK, show many aberrations.

|

“Previous corneal refractive surgery of any kind may have left the patient with—for lack of a better description—a multifocal cornea,” notes Dr. Mackool. “If the patient had myopic LASIK, he will likely have some spherical aberration. If his pupil is small enough that the light rays coming in are essentially parallel, then that spherical aberration won’t come into play; but if he doesn’t have a small pupil, the spherical aberration is more likely to bother him. Similarly, irregular astigmatism is a relative contraindication because the more irregular the astigmatism, the greater the image degradation and the greater the need for a small pupil to be able to function well. (Of course, the amount of benefit you derive from having a smaller pupil is affected by the type of multifocal IOL you’re implanting, because different multifocal IOLs function differently.) The message here is that not everyone who has had LASIK will have trouble with a multifocal implant, but the situation is less predictable.

“That means it’s important to have a discussion with the patient so he understands what he’s signing up for,” Dr. Mackool continues. “If that individual is absolutely committed to the idea of trying a multifocal lens, he should understand there’s a significant possibility that he’ll need to use a miotic agent postoperatively to achieve satisfactory acuity, especially in the evening. His crystalline lens may have been compensating for whatever spherical aberration the LASIK left in the cornea, and the IOL may not do that. The IOL will also be smaller than the crystalline lens, which could make a difference.

“Most surgeons will be on the lookout for things like corneal epithelial dystrophy, irregular corneal surfaces and macular degeneration,” he adds. “All of those things can compromise the outcome of implanting a multifocal in a patient who is hoping and expecting to be spectacle-free. But subtle things like spherical aberration after myopic LASIK are also very important issues that need to be discussed with the patient.”

Dr. Wallace notes another issue with post-LASIK candidates. “Because these individuals have already had refractive surgery, they tend to have higher expectations,” he says. “They expect everything to be perfect. We have to let them know that of all the people we see, they may be the least predictable in terms of outcome. Because they’ve had a change in corneal shape, we have to use fudge factors in the IOL power calculation formulas in order to give them decent results. So we talk to these patients about possibly having to add a piggyback lens later if we don’t get the result we want. It’s important to lower their expectation level.”

Is Femtosecond the Answer?

“Femtosecond laser cataract surgery is exciting technology, and I think it will continue to get better as time goes by,” says Dr. Kershner. “It has its detractors, but then people badmouthed phaco when it first came out, too. Unfortunately, though, many surgeons look to the femtosecond laser as a way to compensate for their lack of reproducibility and precision when creating corneal incisions and capsulorhexes. I don’t believe the femtosecond laser is going to be the solution to those concerns.”

Dr. Kershner offers several reasons femtosecond laser technology may not be a major advantage when it comes to fine-tuning cataract surgery for better multifocal outcomes:

• Computer accuracy is no guarantee of a good outcome. “One of the problems with this technology is that it will do whatever you tell it to and accomplish that with great precision, but it’s only as good as your ability to know what you want it to do,” he says. “Yes, the femtosecond laser can make an incision with incredible accuracy, just as an excimer laser can remove tissue to the level of 0.25 of a micron. All it’s going to do, though, is make you repeat your mistakes more precisely.

“I’ve seen published pictures of femtosecond laser astigmatic keratotomy and clear corneal incisions that were clean and beautiful—but not in the right places,” he notes. “They were perfect arcs, and centered at the corneal limbus, but not centered exactly over the pupil. They looked good, but would they have produced a perfect refractive outcome? Not a chance. The whole point of incision placement is to maximize the refractive enhancement and minimize the refractive error.

“When it comes to the capsulotomy, something I know a lot about, there is yet to be a published study that demonstrates that—assuming the lens is centered—the perfectly round, centered capsulorhexis made with a femtosecond laser results in better visual outcomes than an irregular, continuous tear capsulorhexis,” he adds. “Indeed, there are studies that show that the incidence of inadvertent capsular tears is greater with the sawtooth edge of a femtosecond capsulotomy than with a continuous smooth-tear capsulorhexis.”

• A manual capsulorhexis provides information about the capsule that a laser capsulotomy does not. “Back in 1994 I developed the first capsulorhexis cystotome forceps,” says Dr. Kershner. “That simplified the capsular tear by letting the surgeon open the capsule and create the tear with a single instrument through a 1-mm incision. The added benefit of never letting go of the anterior capsular flap was to give the surgeon the opportunity to assess the capsule. We used to call it ‘reading the capsule.’

“The anterior lens capsule is a true basement membrane, with an anterior layer of simple cuboidal epithelial cells beneath it,” he explains. “Being composed of Type IV collagen and glycosaminoglycans, it is normally quite elastic. At only 14 µm in thickness (ranging from about 8 to 28 µm) it is thickest anteriorly and thinnest posteriorly where there are no cells. Because there are no cells on the posterior lens capsule, it is at least half as thick as the anterior lens capsule. When you’re manually tearing the anterior capsule you can feel the nature of it. Is it elastic or brittle? Does it tear rapidly or slowly? This gives you insight into the nature of the posterior capsule. Thus, if you get an inadvertent posterior capsule rupture at the beginning of a case, you will have seen it coming because you had the ability to read the capsule. With femto technology, the surgeon is separated from his surgical field.”

Even a perfectly round capsulorhexis is only as good as what you do before and after it and how you implant the lens. “Both zonular integrity and capsular strength are critical to centration of the IOL,” Dr. Kershner says. “If you have any suggestion that the zonules have been compromised or that the capsule is gossamer thin, irregular or oval-shaped, it is not going to suspend the lens in the center and you should not be implanting a multifocal lens. A spherical lens may be a better choice, as it will allow you to proceed without complications. A multifocal lens will not.

|

Preoperative Pearls

These strategies will help ensure a good outcome when implanting a multifocal IOL:

• If you’re just starting to offer multifocal lenses, prepare before jumping in. Dr. Mackool offers some advice to surgeons who may be considering offering multifocal implants to their patients. “First, choose your initial patients wisely,” he says. “Choose those who are highly motivated, have small pupils and no other potentially complicating factors such as more than 1 D of astigmatism. Second, have your plans in order for what you’ll do when a patient is not happy. What procedure will you use if you don’t get rid of his astigmatism and/or other refractive error? PRK? LASIK? Limbal relaxing incisions? You don’t want to be saying, ‘Oh, I’m not sure what to do; let me find a doctor who can take care of this for you.’ Yes, if the problem is vitreoretinal, you’ll likely want to send the patient to a vitreoretinal specialist, but most problems will be refractive issues. The more prepared you are to deal with those, the better. Third, have a clear presentation regarding the multifocal lens options, and rehearse it before you actually present it to any patients. I suspect that many surgeons offering these lenses for the first time haven’t thought this through. Fourth, have a handout available for the patient to read before she sees you. My patients read four pages of information about multifocal IOLs—or toric lenses, if they have astigmatism—before they see me for the exam.”

• Check pupil size and function before the patient is dilated. “Pupil size is definitely an issue because each multifocal is slightly different,” notes Dr. Kershner. “The entrance pupil will dictate which part of the refractive surface is being utilized under any given lighting condition. If you don’t check the function of the pupillary sphincter under different lighting conditions—scotopic, mesopic and photopic—you are going to get burned. That’s why the surgeon should never see these patients post-dilation, the way most ophthalmologists do. You really need to see how the physiology of their eyes works firsthand before anyone has pharmacologically altered them. This is critical with these patients.”

• Don’t wait to manage pupil size issues postoperatively. “Some doctors manage pupil size issues reactively rather than proactively,” says Dr. Kershner. “If the pupil needs to be smaller to improve vision after the implantation, they say ‘I’ll just put you on pilocarpine.’ That’s not an answer. I think it’s much better to determine what the patient’s pupil size and function is before the surgery rather than trying to fix the problem after the fact with drugs or a laser.”

• Get the most accurate biometry possible. “Whether you use laser interferometry or ultrasonic biometry, you need to know the precise dimensions that light travels through to the fovea, down to a hundredth of a millimeter,” says Dr. Kershner. “That means accurately measuring the anterior chamber depth, distance from the central lens to the fovea and axial length of the eye. Unfortunately, many surgeons rely upon averages when making their IOL calculations; they figure it’s close enough. The reality is, some patients have a very shallow anterior segment and very deep posterior segment. Others are the reverse. Where we expect to place the IOL within the capsular bag does not always correlate with the actual nodal point of the eye. Admittedly, current formulas don’t allow us to maximize the value of this information, but it’s valuable information, nonetheless.”

Dr. Kershner notes that the lens manufacturers are beginning to respond to the need for more precision. “This is reflected in many lens manufacturers now offering these lenses in quarter-diopter steps,” he points out. “I’ve argued for years that every lens should be labeled with its exact power, instead of rounding the power to the nearest half-diopter and putting that on the box. If every IOL manufactur-er were to label the actual power of each lens in the box, then we could se-lect the individual lens that’s as close as possible to what we need, which would further improve our outcomes.”

• Consider doing OCT on all of these patients. “You definitely want to check for any retinal pathology,” says Dr. Crotty. “Sometimes if you’re dealing with a fairly dense cataract it’s not that easy to see. You might miss a subtle epiretinal membrane, early stages of macular hole development or macular degeneration. In many cases if we’re suspicious we will send out for a retinal consult. If you proceed on the assumption that everything is fine and implant a multifocal, and then the patient actually has retinal pathology, there’s no way you’re going to be able to convince the patient that it was there before surgery.”

• Pay close attention to the details. Dr. Crotty notes that it’s crucial to have a preop protocol for these patients and pay attention to the details. “You don’t want to look back and think, ‘I shouldn’t have put this lens in,’” he says. “Simple things like the condition of the ocular surface will impact the outcome. If you cannot get that ocular surface pristine, then that patient is not a candidate for a multifocal lens. When I see unhappy patients who came to us from another practice, it’s generally because somebody didn’t pay close enough attention to the details.”

• If the cornea could be a potential problem, don’t do a quick fix and proceed to implant a multifocal. “I recently read about a surgeon who addressed the problem of a less-than-ideal corneal surface by applying an amniotic membrane for a few days to heal the cornea, and then proceeded to implant a premium lens,” says Dr. Kershner. “I think this is shortsighted. We all would agree that the treatment of corneal surface dry-eye disease, meibomitis, blepharitis and the like, is critical before attempting any intraocular surgery. Unless the surgeon is confident that an irregular corneal refractive surface is completely and permanently corrected, any advanced optic IOL is contraindicated. The adverse conditions that created that problem in the first place didn’t permanently go away just because you put a membrane graft on for three days or the patient used topical antibiotics for a month. Whatever underlying disease processes are present need to be fully addressed, or you can be assured that they will come back to haunt you.”

• Plan your primary incision carefully. Dr. Kershner says incision construction is a potential source of trouble. “It’s very important that the surgeon pay particular attention to incision construction and placement and its planned effect in altering corneal topography,” he notes. “I’ve been performing astigmatic keratotomy for decades. Based upon a very large body of accumulated data, the refractive results of our astigmatic keratotomy and surgical incision placement are quite predictable. The fact is, any time you incise the cornea you are changing the corneal topography—period. If the surgeon fails to take into account the position, size, length and geometry of the surgical incision for cataract removal, irrespective of what tools will be used to create the incision, the refractive outcome will not achieve target goals. There are surgeons who say, ‘I’m not too worried about that because I can always do a touchup with LASIK.’ The problem with this reasoning is that the patient may never give you the opportunity to go back and make up for any refractive shortcomings. The surgeon must be absolutely confident that what he thinks he is going to get is exactly what the patient ends up with.”

Intraoperative Pearls

• Video every surgery. “A key part of my effort to fine-tune my surgical outcomes is to monitor what we are doing while we are doing it,” says Dr. Kershner. “From a practical standpoint, you haven’t had someone in the operating room critiquing your technique since you were a resident. But that doesn’t mean you can’t honestly critique yourself. The only way to do that is to sit back and review every surgery that you have done at the end of the day by watching the digital recording. Then, when you are absolutely confident of reproducibility and an unexpected outcome occurs, you can go back and review the recording of the surgery to see if anything was done that could have caused the aberrant outcome, and whether you could have done anything to avoid it. If we find the smoking gun, we need to change what we are doing so that it never happens again.”

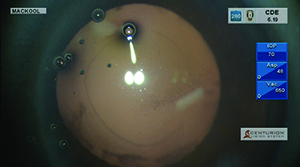

• Don’t overstretch the pupil. “Multifocal lens patients usually benefit from having a small pupil,” notes Dr. Mackool. “You don’t want to wind up with a big pupil, so stretching small pupils with retractors or rings is not a good idea. A lot of those pupils won’t return to their normal, desirable small size. It’s better to use iris retractors and only enlarge the pupil to the minimum size necessary for the procedure. For me, that’s about 4.5 mm. Of course, it depends on the technique you’re using. But if you’re doing phaco chop and dividing the nucleus into small segments, you don’t really need a large pupil to get through the case.”

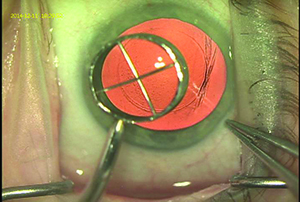

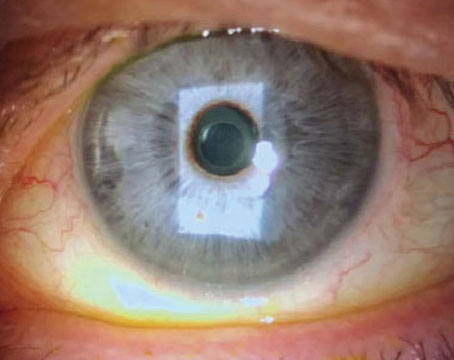

• Consider using a corneal marker to help create the capsulorhexis. “We use a 6-mm optical zone corneal marker to mark the corneal surface—with the center of the optical zone as the central visual axis—to guide us in the intended placement and size of the capsulorhexis,” says Dr. Wallace. (See picture, above.) “We described this technique in a 2003 article.1 When making the manual capsulorhexis we stay just inside that visual guide, almost always producing a 5- to 5.5-mm capsulotomy. This method isn’t as precise as a femtosecond laser, but it works pretty well, and we haven’t found the precision of the capsulorhexis to be a major issue in our outcomes. However, we feel that using a guide is important in terms of refractive outcomes because you want the capsule to overlap the optic so it doesn’t move around inside the eye and cause changes in the refraction postop. Using the guide ensures that that happens.”

|

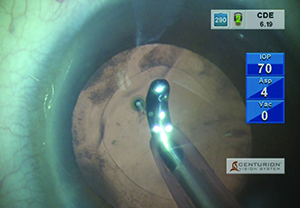

• Make sure any future lens exchange will be as easy as possible. “You should anticipate that you might have to exchange the multifocal lens,” says Dr. Mackool. “That means that you want to do whatever you can to facilitate that removal. There are basically two things that will facilitate an IOL exchange: First, aim to have the edges of the capsulorhexis overlap the optic by 0.5 mm or more in all meridians. If the capsulorhexis is larger than the optic, the anterior and posterior capsule will fuse together, often very tightly; separating them can be difficult and can result in opening the posterior capsule.

“Second, it’s very desirable to remove epithelial cells from the undersurface of the anterior capsule,” he adds. “You don’t have to do it for 360 degrees; 180 degrees is plenty. Doing that greatly delays adherence of the anterior capsule to the surface of the IOL optic. This makes it much easier to perform the viscodissection maneuver that’s needed to free the IOL from the capsule so the implant can be removed without damaging the capsule, and a new implant can be placed in the capsular sac.” (See picture, p. 28.)

• Center the lens. Dr. Kershner points out that the intracapsular positioning of a multifocal lens is far more critical than it ever was with monofocal lenses. “With spherical lenses, if you were slightly off-center, if the capsular opening into the bag wasn’t completely round or there was zonular dehiscence, the lens optic would still be forgiving,” he points out. “With multifocal and toric optics, that’s not the case. These lenses demand perfect centration and planar positioning to function optimally. If you can’t deliver that, you shouldn’t be implanting them.”

Dr. Wallace says he likes the middle of the optic to be about half a millimeter nasal. “The sweet spot is not in the middle of the pupil,” he notes. “Fortunately, these lenses tend to stick pretty well; they don’t move that much.”

• Be aware that you might have to deal with “retinal astigmatism.” “A patient may have a posterior staphyloma, which can create retinal astigmatism, a term I coined back in 1973,” says Dr. Mackool. “I became aware of this issue back in the days of intracapsular cataract surgery. We’d remove the cataract and then measure the patient for spectacles postoperatively. I found that a lot of patients with long, myopic eyes would have a disparity between their corneal astigmatism and their refractive astigmatism, in both amount and axis. In fact, there were patients with no corneal astigmatism who had significant refractive astigmatism. It turned out that they had a posterior staphyloma and a tilted retina, and they needed an astigmatic correction to see better. That’s the condition I call retinal astigmatism.

“Unfortunately, there is no way to measure this when the crystalline lens is still in place,” he continues. “So the only way to determine the presence or absence of that condition—which of course you need to correct if your aim is the best possible uncorrected acuity—is to measure the vision after the cataract is removed by using the ORA device or doing an aphakic refraction outside the operating room, which would mean leaving the patient aphakic for a while. We do that commonly on patients who have had corneal refractive procedures or have keratoconus, to determine their required IOL power and amount of astigmatism. If we find significant astigmatism, we can manage it using limbal relaxing incisions or a toric IOL. It can also be addressed with a corneal refractive procedure at a later date.”

Postop Pearls

• Expect to YAG earlier than with other patients. “Multifocal patients who end up needing YAG laser treatment tend to need it earlier than monofocal lens patients,” says Dr. Wallace. “Of course, many of these patients are younger than your average patient, so their capsules will tend to opacify sooner. Also, they usually lose their near vision first. The capsule may not appear to be that bad, but they’ll be complaining about having trouble reading up close.”

• When analyzing your pooled, cumulative, postoperative outcomes data, don’t ignore the surgical outcome outliers—learn from them. "In all my years as a surgeon, I’ve yet to have a big postoperative surprise,” says Dr. Kershner. “It’s not because I am so wonderful a surgeon, it’s simply that I carefully analyze the results of what I am doing. This is one of the key things I have consistently done in my practice to optimize my results. I don’t ignore the outliers when they occur, and I don’t blame the patient. I assume that we either missed something in our surgical plan or did something other than what we should have done. Today it’s easy to track all of your pre- and postop results to see exactly what you’re getting. Create the graphs, look at the scatterplots and the range of errors and see how closely your outcomes matched your expectations. The dots that don’t fall on the line are the outcomes that are the most important to increasing refractive precision.

“Patients are wowed by our technology,” he adds. “Today they expect their cataract to be removed by a laser. But I like to point out to my patients that a good surgical outcome depends as much on the surgeon as on cutting-edge technology. When something does not go according to plan, it’s the surgeon’s experience that saves the day, not the technology. A million-dollar laser is like a sophisticated fly-by-wire jumbo jetliner; it’s the experience of the operator that makes the technology work. When a flock of seagulls shuts down both of your jet engines on takeoff, it’s the experience of a senior pilot like ‘Sully’ Sullenberger that saves the passengers and airplane. And how do you get that experience? It’s not how many surgeries you’ve done; it’s how carefully you have monitored them. It makes all the difference. So don’t ignore your outliers, focus on them and learn from them.” REVIEW

1. Wallace RB III. Capsulotomy diameter mark. J Cataract Refract Surg 2003;29:1866-1868.